Related Research Articles

Hebrew grammar is the grammar of the Hebrew language.

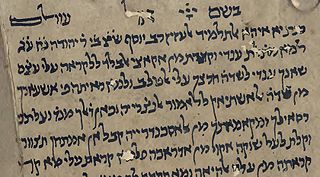

The Masoretic Text is the authoritative Hebrew and Aramaic text of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) in Rabbinic Judaism. The Masoretic Text defines the Jewish canon and its precise letter-text, with its vocalization and accentuation known as the mas'sora. Referring to the Masoretic Text, masorah specifically means the diacritic markings of the text of the Jewish scriptures and the concise marginal notes in manuscripts of the Tanakh which note textual details, usually about the precise spelling of words. It was primarily copied, edited, and distributed by a group of Jews known as the Masoretes between the 7th and 10th centuries of the Common Era (CE). The oldest known complete copy, the Leningrad Codex, dates from the early 11th century CE.

Abraham ben Meir Ibn Ezra was one of the most distinguished Jewish biblical commentators and philosophers of the Middle Ages. He was born in Tudela, Taifa of Zaragoza.

The Masoretes were groups of Jewish scribe-scholars who worked from around the end of the 5th through 10th centuries CE, based primarily in the Jewish centers of the Levant and Mesopotamia. Each group compiled a system of pronunciation and grammatical guides in the form of diacritical notes (niqqud) on the external form of the biblical text in an attempt to standardize the pronunciation, paragraph and verse divisions, and cantillation of the Hebrew Bible for the worldwide Jewish community.

As the Old Testament was written in Hebrew, Hebrew has been central to Judaism and Christianity for more than 2000 years.

Dunash ha-Levi ben Labrat was a medieval Jewish commentator, poet, and grammarian of the Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain. He is known for his philological commentary, Teshuvot Dunash, and for his liturgical poems D'ror Yiqra and D'vai Haser.

Medieval Hebrew was a literary and liturgical language that existed between the 4th and 19th century. It was not commonly used as a spoken language, but mainly in written form by rabbis, scholars and poets. Medieval Hebrew had many features distinguishing it from older forms of Hebrew. These affected grammar, syntax, sentence structure, and also included a wide variety of new lexical items, which were either based on older forms or borrowed from other languages, especially Aramaic, Koine Greek and Latin.

Rishonim were the leading rabbis and poskim who lived approximately during the 11th to 15th centuries, in the era before the writing of the Shulchan Aruch and following the Geonim. Rabbinic scholars subsequent to the Shulchan Aruch are generally known as acharonim.

Hasdai ibn Shaprut born about 915 at Jaén, Spain; died about 970 at Córdoba, Andalusia, was a Jewish scholar, physician, diplomat, and patron of science.

David Kimhi (1160–1235), also known by the Hebrew acronym as the RaDaK (רַדָּ״ק), was a medieval rabbi, biblical commentator, philosopher, and grammarian.

Dunash ibn Tamim was a Jewish tenth century scholar, and a pioneer of scientific study among Arabic-speaking Jews. His Arabic name was أبو سهل Abu Sahl; his surname, according to an isolated statement of Moses ibn Ezra, was "Al-Shafalgi," perhaps after his (unknown) birthplace. Another name referring to him is Adonim.

Joseph Kimchi or Qimḥi (1105–1170) was a medieval Jewish rabbi and biblical commentator. He was the father of Moses and David Kimhi, and the teacher of Rabbi Menachem Ben Simeon and poet Joseph Zabara.

Jonah ibn Janah or ibn Janach, born Abū al-Walīd Marwān ibn Janāḥ, , was a Jewish rabbi, physician and Hebrew grammarian active in al-Andalus. Born in Córdoba, ibn Janah was mentored there by Isaac ibn Gikatilla and Isaac ibn Mar Saul, before he moved around 1012, due to the sacking of the city by Berbers. He then settled in Zaragoza, where he wrote Kitab al-Mustalhaq, which expanded on the research of Judah ben David Hayyuj and led to a series of controversial exchanges with Samuel ibn Naghrillah that remained unresolved during their lifetimes.

Tobiah ben Eliezer was a Talmudist and poet of the 11th century, author of Lekach Tov or Pesikta Zutarta, a midrashic commentary on the Pentateuch and the Five Megillot.

Menahem ben Saruq was a Spanish-Jewish philologist of the tenth century CE. He was a skilled poet and polyglot. He was born in Tortosa around 920 and died around 970 in Cordoba. Menahem produced an early dictionary of the Hebrew language. For a time he was the assistant of the great Jewish statesman Hasdai ibn Shaprut, and was involved in both literary and diplomatic matters; his dispute with Dunash ben Labrat, however, led to his downfall.

Peshat is one of the two classic methods of Jewish biblical exegesis, the other being Derash. While Peshat is commonly defined as referring to the surface or literal (direct) meaning of a text, or "the plain literal meaning of the verse, the meaning which its author intended to convey", numerous scholars and rabbis have debated this for centuries, giving Peshat many uses and definitions.

Benjamin Wolf ben Samson Heidenheim was a German exegete and grammarian.

Jewish commentaries on the Bible are biblical commentaries of the Hebrew Bible from a Jewish perspective. Translations into Aramaic and English, and some universally accepted Jewish commentaries with notes on their method of approach and also some modern translations into English with notes are listed.

Jewish printers were quick to take advantages of the printing press in publishing the Hebrew Bible. While for synagogue services written scrolls were used, the printing press was very soon called into service to provide copies of the Hebrew Bible for private use. All the editions published before the Complutensian Polyglot were edited by Jews; but afterwards, and because of the increased interest excited in the Bible by the Reformation, the work was taken up by Christian scholars and printers; and the editions published by Jews after this time were largely influenced by these Christian publications. It is not possible in the present article to enumerate all the editions, whole or partial, of the Hebrew text. This account is devoted mainly to the incunabula.

Azharot are didactic liturgical poems on, or versifications of, the 613 commandments in rabbinical enumeration. The first known example are 'Ata hinchlata' and 'Azharat Reishit', recited to this day in some Ashkenazic and Italian communities, and dating back to early Geonic times. Other versions appear in the tenth century Siddur of Saadia Gaon, as well as by two Spanish authors of the Middle Ages: Isaac ben Reuben Albargeloni and Solomon ibn Gabirol and the French author Elijah ben Menahem HaZaken.

References

- ↑ "Jewish Encyclopedia" . Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Encyclopædia Britannica" . Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Judaica, s.v. "Masorah" (2nd ed.).

- ↑ "Jewish Encyclopedia" . Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Judaica, s.v. "Masorah" (2nd ed.).

- ↑ "Jewish Encyclopedia" . Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Judaica, s.v. "Rashi" (2nd ed.).

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Judaica, s.v. "Ibn Ezra, Abraham" (2nd ed.).

- ↑ "Jewish Encyclopedia" . Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Judaica, s.v. "Kimhi, David" (2nd ed.).

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Judaica, s.v. "Hebrew Language" (2nd ed.).

- ↑ "Jewish Encyclopedia" . Retrieved March 10, 2013.