Salah Abdul Rasool Al Blooshi is a Bahraini, who was held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detainment camps, in Cuba.

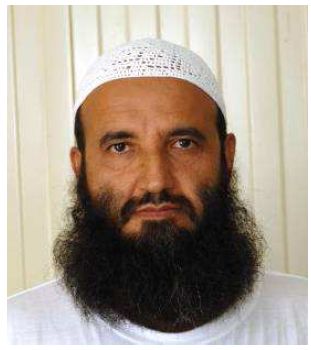

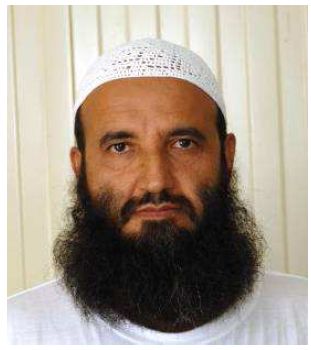

Issa Ali Abdullah al Murbati is a citizen of Bahrain who was held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detainment camps, in Cuba. Al Murbati's Guantanamo Internment Serial Number was 52. American counter-terrorism analysts estimate he was born in 1965, in Manama, Bahrain.

Omar Amer Deghayes is a Libyan citizen who had legal residency status with surviving members of his family in the United Kingdom since childhood. He was arrested in Pakistan in 2002. He was held by the United States as an enemy combatant at Guantanamo Bay detention camp from 2002 until December 18, 2007. He was released without charges and returned to Britain, where he lives. His Guantanamo Internment Serial Number was 727. Deghayes says he was blinded permanently in one eye, after a guard at Guantanamo gouged his eyes with his fingers. Deghayes was never charged with any crime at Guantanamo.

Hajji Shahzada is a citizen of Afghanistan who was held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detention camps, in Cuba. Shahzada's Guantanamo Internment Serial Number was 952. Joint Task Force Guantanamo counter-terrorism analysts estimate that Shahzada was born in 1959, in Belanday, Afghanistan.

Abdullah Mujahid is a citizen of Afghanistan who is still held in extrajudicial detention after being transferred from United States Guantanamo Bay detainment camps, in Cuba — to an Afghan prison.

Said Salih Said Nashir is a citizen of Yemen, held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detainment camps, in Cuba. His Internment Serial Number is 841.

Awal Gul was a citizen of Afghanistan who died in the United States's Guantanamo Bay detention camps in Cuba after nine years of imprisonment without charge.

Sami Abdul Aziz Salim Allaithy Alkinani is an Egyptian professor who was held in the Guantanamo Bay detention camps, in Cuba. His Guantanamo Internment Serial Number was 287. Analysts reported that he was born on October 28, 1956, in Shubrakass Egypt. He was repatriated to Egypt on September 30, 2005. He was later classified by the United States Department of Defense as a no longer enemy combatant.

Hammdidullah, a.k.a.Janat Gul, is a citizen of Afghanistan who was held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detainment camp, in Cuba. American counter-terror analysts estimate he was born in 1973, in Sarpolad, Afghanistan.

Abdul Baseer Nazim is a citizen of Afghanistan who is still held in extrajudicial detention after being transferred from United States Guantanamo Bay detainment camps, in Cuba — to an Afghan prison.

Faris Muslim al Ansari is a citizen of Afghanistan who was seventeen years old when captured and held in the United States's Guantanamo Bay detention camps, in Cuba. His Guantanamo Internment Serial Number was 253. American intelligence analysts estimate that Al Ansari was born in 1984 in Mukala, Yemen.

Jawad Jabber Sadkhan is a citizen of Iraq who was held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detainment camps, in Cuba. Sadkhan's Guantanamo Internment Serial Number was 433.

Abib Sarajuddin is a citizen of Afghanistan, who was held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detention camps, in Cuba. His Guantanamo Internment Serial Number was 458. Guantanamo intelligence analysts estimate that he was born in 1942.

Hajji Sahib Rohullah Wakil is a citizen of Afghanistan who was held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detention camps, in Cuba. His Guantanamo Internment Serial Number was 798. American intelligence analysts estimate he was born in 1962, in Jalalabad, Afghanistan. He has since been transferred from Guantanamo Bay to the American wing of the Pol-e-Charkhi prison in Kabul, Afghanistan. On November 18, 2019, the U.S. Department of the Treasury designated him for supporting activities of the ISIS branch in Afghanistan.

Sabar Lal Melma was a citizen of Afghanistan who was held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detainment camps, in Cuba. Sabar Lal Melma's Guantanamo Internment Serial Number was 801. American intelligence analysts estimate that Sabar Lal Melma was born in 1962, Darya-e-Pech, Afghanistan.

Ha'il Aziz Ahmad Al Maythal is a citizen of Yemen, who was held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detention camp, in Cuba. American intelligence analysts estimate that he was born in 1977, in Zemar, Yemen.

Haji Ghalib is a citizen of Afghanistan who was held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detention camps, in Cuba. His Guantanamo Internment Serial Number was 987. Guantanamo counter-terrorism analysts estimate he was born in 1963, in Nangarhar, Afghanistan. Ghalib was repatriated on February 28, 2007.

Ibrahim Fauzee is a citizen of the Maldives, who was held in extrajudicial detention in the United States's Guantanamo Bay detention camps, in Cuba.

Adil Hadi al Jazairi Bin Hamlili is a citizen of Algeria who was held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detainment camps, in Cuba. The US Department of Defense reports that Bin Hamlili was born on 26 June 1976, in Oram (Oran) [sic] Algeria. His Guantanamo Internment Serial Number was 1452.

Ayman Saeed Abdullah Batarfi is a Yemeni doctor who was held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detention camps, in Cuba. His Guantanamo Internment Serial Number was 627.