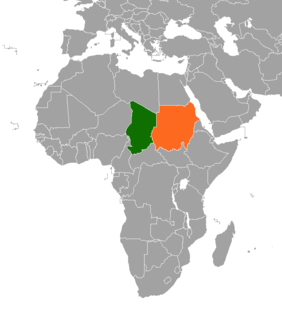

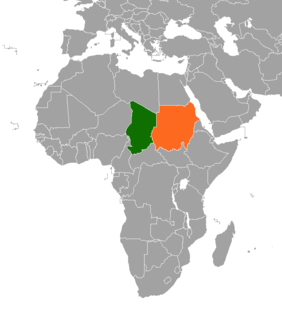

Chad, officially the Republic of Chad, is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It borders Libya to the north, Sudan to the east, the Central African Republic to the south, Cameroon and Nigeria to the southwest, and Niger to the west. Due to its distance from the sea and its largely desert climate, the country is sometimes referred to as the "Dead Heart of Africa".

The Chad National Army consists of the five Defence and Security Forces listed in Article 185 of the Chadian Constitution that came into effect on 4 May 2018. These are the National Army, the National Police, the National and Nomadic Guard (GNNT) and the Judicial Police. Article 188 of the Constitution specifies that National Defence is the responsibility of the Army, Gendarmerie and GNNT, whilst the maintenance of public order and security is the responsibility of the Police, Gendarmerie and GNNT.

Hissène Habré, also spelled Hissen Habré, was a Chadian politician and convicted war criminal who served as the 5th president of Chad from 1982 until he was deposed in 1990.

Idriss Déby Itno was a Chadian politician and military officer who was the president of Chad from 1990 until his death in 2021.

Goukouni Oueddei is a Chadian politician who served as President of Chad from 1979 to 1982.

The 1975 coup d'état in Chad that terminated Tombalbaye's government received an enthusiastic response in the capital N'Djamena. Félix Malloum emerged as the chairman of the new Supreme Military Council, and the first days of the new regime were celebrated as many political prisoners were released. His government included more Muslims from northern and eastern Chad, but ethnic and regional dominance still remained very much in the hands of southerners.

The Transitional Government of National Unity was the coalition government of armed groups that nominally ruled Chad from 1979 to 1982, during the most chaotic phase of the long-running civil war that began in 1965. The GUNT replaced the fragile alliance led by Félix Malloum and Hissène Habré, which collapsed in February 1979. GUNT was characterized by intense rivalries that led to armed confrontations and Libyan intervention in 1980. Libya intervened in support of the GUNT's President Goukouni Oueddei, against the former GUNT Defence Minister Hissène Habré.

The People's Armed Forces was a Chadian insurgent group composed of followers of Goukouni Oueddei after the schism with Hissène Habré in 1976. With an ethnic base in the Teda clan of the Toubou from the Tibesti area of northern Chad, the force was armed by Libya and formed the largest component of the Transitional Government of National Unity (GUNT) coalition army opposing Habré. FAP troops rebelled against their Libyan allies in the latter part of 1986. Many of them were subsequently integrated into the national army, the Chadian National Armed Forces (FANT), and participated in the 1987 attempt to drive Libya out of Chadian territory.

Operation Épervier was the French military presence in Chad from 1986 until 2014.

The Chadian–Libyan conflict was a series of military campaigns in Chad between 1978 and 1987, fought between Libyan and allied Chadian forces against Chadian groups supported by France, with the occasional involvement of other foreign countries and factions. Libya had been involved in Chad's internal affairs prior to 1978 and before Muammar Gaddafi's rise to power in Libya in 1969, beginning with the extension of the Chadian Civil War to northern Chad in 1968. The conflict was marked by a series of four separate Libyan interventions in Chad, taking place in 1978, 1979, 1980–1981 and 1983–1987. In all of these occasions Gaddafi had the support of a number of factions participating in the civil war, while Libya's opponents found the support of the French government, which intervened militarily to support the Chadian government in 1978, 1983 and 1986.

Operation Manta was a French military intervention in Chad between 1983 and 1984, during the Chadian–Libyan conflict. The operation was prompted by the invasion of Chad by a joint force of Libyan units and Chadian Transitional Government of National Unity (GUNT) rebels in June 1983. While France was at first reluctant to participate, the Libyan air-bombing of the strategic oasis of Faya-Largeau starting on July 31 led to the assembling in Chad of 3,500 French troops, the biggest French intervention since the end of the colonial era.

Abbas Koty Yacoub was a Chadian political figure and rebel leader.

General Mahamat Nouri is a Chadian insurgent leader who currently commands the Union of Forces for Democracy and Development (UFDD). A Muslim from northern Chad, he began his career as a FROLINAT rebel, and when the group's Second Army split in 1976 he sided with his kinsman Hissène Habré. As Habré's associate he obtained in 1978 the first of the many ministerial positions in his career, becoming Interior Minister in a coalition government. When Habré reached the presidency in 1982, Nouri was by his side and played an important role in the regime.

Chad–United States relations are the international relations between Chad and the United States.

The populations of eastern Chad and western Sudan established social and religious ties long before either nation's independence, and these remained strong despite disputes between governments. In recent times, relations have been strained due to the conflict in Darfur and a civil war in Chad, which both governments accuse the other of supporting.

Chad achieved independence in 1960. At the time, it had no armed forces under its own flag. Since World War I, however, southern Chad, particularly the Sara ethnic group, had provided a large share of the Africans in the French army. Chadian troops also had contributed significantly to the success of the Free French Forces in World War II. In December 1940, two African battalions began the Free French military campaign against Italian forces in Libya from a base in Chad, and at the end of 1941, a force under Colonel Jacques Leclerc participated in a spectacular campaign that seized the entire Fezzan region of southern Libya. Colonel Leclerc's 3,200-man force included 2,700 Africans, the great majority of them southerners from Chad. These troops went on to contribute to the Allied victory in Tunisia. Chadians, in general, were proud of their soldiers' role in the efforts to liberate France and in the international conflict.

The Chadian Civil War of 1965–1979 was waged by several rebel factions against two Chadian governments. The initial rebellion erupted in opposition to Chadian President François Tombalbaye, whose regime was marked by authoritarianism, extreme corruption, and favoritism. In 1975 Tombalbaye was murdered by his own army, and a military government headed by Félix Malloum emerged and continued the war against the insurgents. Following foreign interventions by Libya and France, the fracturing of the rebels into rival factions, and an escalation of the fighting, Malloum stepped down in March 1979. This paved the way for a new national government, known as "Transitional Government of National Unity" (GUNT).

Acheikh Ibn-Oumar is a Chadian politician and military leader. In the 1980s he led the Democratic Revolutionary Council, a military-political group opposing the government of President Hissène Habré. He studied mathematics in France, and then, in the late 70's, joined the historical Chadian revolutionary mouvement FROLINAT . He held several cabinet positions within the GUNT, led by Goukouni Weddeye . In November 1984, Acheikh Ibn-Oumar was arrested in Tripoli and then transferred to Tibesti where he remained in detention until December 1985, because of serious divergences with both late Colonel Gaddafi and Goukouni. After a short-lived reconciliation with Goukouni, in 1986, Acheikh Ibn-Oumar and the CDR withdrew support for Goukouni Oueddei, leaving Goukouni isolated. Libya switched support from Goukouni to Ibn-Oumar, backing Ibn-Oumar's forces as they took Ennedi in northern Chad, and sending aircraft and tanks to help Ibn-Oumar defend against a counter-attack by Toubou forces loyal to Goukouni. In mid-November 1986, supported by Libya, Ibn-Oumar became president of a newly constituted GUNT, consisting of seven of the original eleven factions. In 1987 Ibn-Oumar's militia was driven into Darfur by French and Chadian forces, fighting the Fur people there.

The Commission of Inquiry into the Crimes and Misappropriations Committed by Ex-President Habré, His Accomplices and/or Accessories was established on December 29, 1990, by the President of Chad, Idriss Déby. Its goal was to investigate the "illegal detentions, assassinations, disappearances, torture, mistreatment, other attacks on the physical and mental integrity of persons; plus all violations of human rights, illicit narcotics trafficking and embezzlement of state funds between 1982 and 1990", when former President Hissène Habré was in power.