The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British Government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman region with a small minority Jewish population. The declaration was contained in a letter dated 2 November 1917 from the United Kingdom's Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour to Lord Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, for transmission to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland. The text of the declaration was published in the press on 9 November 1917.

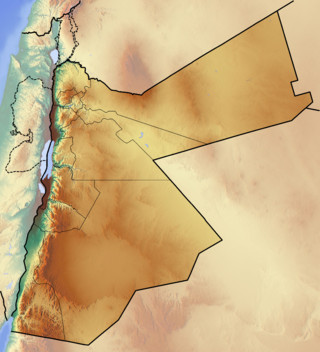

The Emirate of Transjordan, officially known as the Amirate of Trans-Jordan, was a British protectorate established on 11 April 1921, which remained as such until achieving formal independence as the Kingdom of Transjordan in 1946.

Faisal I bin al-Hussein bin Ali al-Hashemi was King of Iraq from 23 August 1921 until his death in 1933. A member of the Hashemite family, he was a leader of the Great Arab Revolt during the First World War, and ruled as the unrecognized King of the Arab Kingdom of Syria from March to July 1920 when he was expelled by the French.

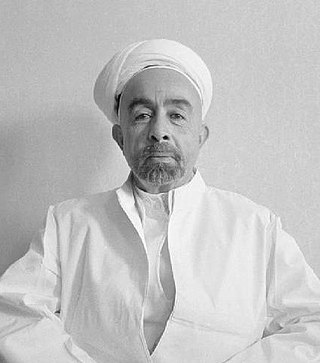

Abdullah I bin Al-Hussein was the ruler of Jordan from 11 April 1921 until his assassination in 1951. He was the Emir of Transjordan, a British protectorate, until 25 May 1946, after which he was king of an independent Jordan. As a member of the Hashemite dynasty, the royal family of Jordan since 1921, Abdullah was a 38th-generation direct descendant of Muhammad.

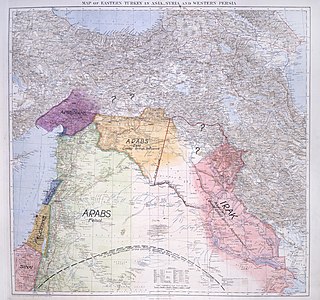

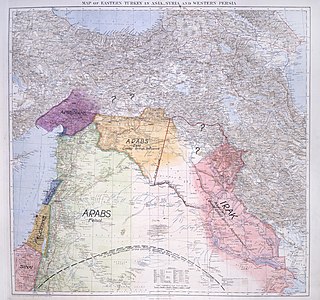

The McMahon–Hussein correspondence is a series of letters that were exchanged during World War I, in which the government of the United Kingdom agreed to recognize Arab independence in a large region after the war in exchange for the Sharif of Mecca launching the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire. The correspondence had a significant influence on Middle Eastern history during and after the war; a dispute over Palestine continued thereafter.

The Jewish aspiration to return to Zion, generally associated with divine redemption, has suffused Jewish religious thought since the destruction of the First Temple and the Babylonian exile.

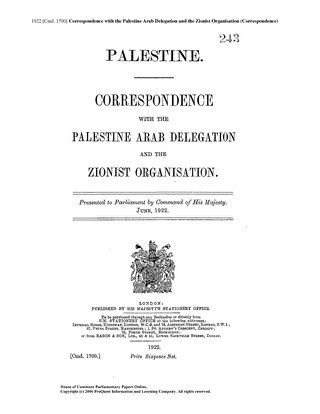

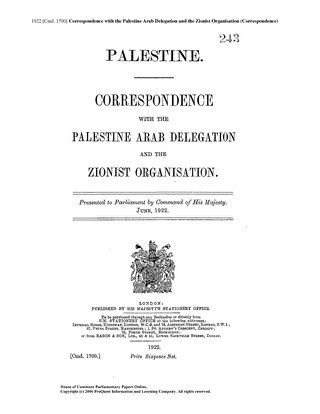

The Churchill White Paper of 3 June 1922 was drafted at the request of Winston Churchill, then Secretary of State for the Colonies, partly in response to the 1921 Jaffa Riots. The official name of the document was Palestine: Correspondence with the Palestine Arab Delegation and the Zionist Organisation. The white paper was made up of nine documents and "Churchill's memorandum" was an enclosure to document number 5. While maintaining Britain's commitment to the Balfour Declaration and its promise of a Jewish national home in Mandatory Palestine, the paper emphasized that the establishment of a national home would not impose a Jewish nationality on the Arab inhabitants of Palestine. To reduce tensions between the Arabs and Jews in Palestine the paper called for a limitation of Jewish immigration to the economic capacity of the country to absorb new arrivals. This limitation was considered a great setback to many in the Zionist movement, though it acknowledged that the Jews should be able to increase their numbers through immigration rather than sufferance.

The Faisal–Weizmann agreement was signed by Emir Faisal, the third son of Hussein ibn Ali al-Hashimi, King of the short-lived Kingdom of Hejaz, and Chaim Weizmann, President of the Zionist Organization on 3 January 1919. Signed two weeks before the start of the Paris Peace Conference, it was presented by the Zionist delegation alongside a March 1919 letter written by T. E. Lawrence in Faisal's name to American Zionist leader Felix Frankfurter as two documents to argue that the Zionist plans for Palestine had prior approval of Arabs.

The White Paper of 1939 was a policy paper issued by the British government, led by Neville Chamberlain, in response to the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine. After its formal approval in the House of Commons on 23 May 1939, it acted as the governing policy for Mandatory Palestine from 1939 to the 1948 British departure. After the war, the Mandate was referred to the United Nations.

Musa Kazim Pasha al-Husayni was a Palestinian politician and statesman. He belonged to the prominent al-Husayni family and was mayor of Jerusalem (1918–1920). He was dismissed as mayor by the British authorities and became head of the nationalist Executive Committee of the Palestine Arab Congress from 1922 until 1934. His death was believed to have been caused by injuries received during an anti-British demonstration.

The modern borders of Israel exist as the result both of past wars and of diplomatic agreements between the State of Israel and its neighbours, as well as an effect of the agreements among colonial powers ruling in the region before Israel's creation. Only two of Israel's five total potential land borders are internationally recognized and uncontested, while the other three remain disputed; the majority of its border disputes are rooted in territorial changes that came about as a result of the 1967 Arab–Israeli War, which saw Israel occupy large swathes of territory from its rivals. Israel's two formally recognized and confirmed borders exist with Egypt and Jordan since the 1979 Egypt–Israel peace treaty and the 1994 Israel–Jordan peace treaty, while its borders with Syria, Lebanon and the Palestinian territories remain internationally defined as contested.

This is a timeline of major events in the history of the modern state of Jordan.

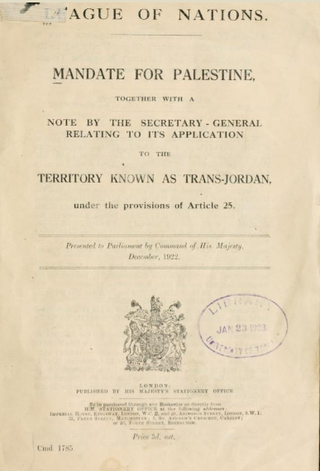

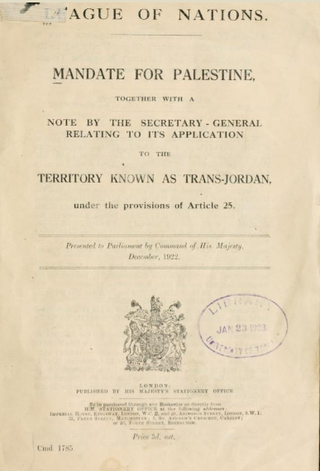

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordan – which had been part of the Ottoman Empire for four centuries – following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I. The mandate was assigned to Britain by the San Remo conference in April 1920, after France's concession in the 1918 Clemenceau–Lloyd George Agreement of the previously agreed "international administration" of Palestine under the Sykes–Picot Agreement. Transjordan was added to the mandate after the Arab Kingdom in Damascus was toppled by the French in the Franco-Syrian War. Civil administration began in Palestine and Transjordan in July 1920 and April 1921, respectively, and the mandate was in force from 29 September 1923 to 15 May 1948 and to 25 May 1946 respectively.

The London Conference of 1939, or St James's Palace Conference, which took place between 7 February – 17 March 1939, was called by the British Government to plan the future governance of Palestine and an end of the Mandate. It opened on 7 February 1939 in St James's Palace after which the Colonial Secretary, Malcolm MacDonald held a series of separate meetings with the Arab Higher Committee and Zionist delegation, because the Arab Higher Committee delegation refused to sit in the same room as the Zionist delegation. When MacDonald first announced the proposed conference he made clear that if no agreement was reached the government would impose a solution. The process came to an end after five and a half weeks with the British announcing proposals which were later published as the 1939 White Paper.

Mandatory Palestine was a geopolitical entity that existed between 1920 and 1948 in the region of Palestine under the terms of the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine.

This is a timeline of intercommunal conflict in Mandatory Palestine.

The Interregnum period in Transjordan was a short period during which Transjordan had no established ruler or occupying power that lasted from the end of the Franco-Syrian War on 25 July 1920 until the Establishment of the Emirate of Transjordan in April 1921.

Establishment of the Emirate of Transjordan refers to the government that was set up in Transjordan on 11 April 1921, following a brief interregnum period.

The Sharifian or Sherifian Solution was an informal name for post-Ottoman British Middle East policy and French Middle East policy of nation-building. As first put forward by T. E. Lawrence in 1918, it was a plan to install the three younger sons of Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi as heads of state in newly created countries across the Middle East, whereby his second son Abdullah would rule Baghdad and Lower Mesopotamia, his third son Faisal would rule Syria, and his fourth son Zeid would rule Upper Mesopotamia. Hussein himself would not wield any political power in these places, and his first son, Ali would be his successor in Hejaz.

The Jordan–Saudi Arabia border is 731 km (454 mi) in length and runs from the Gulf of Aqaba in the south-west to the tripoint with Iraq in the north-east.