In chemistry and thermodynamics, calorimetry is the science or act of measuring changes in state variables of a body for the purpose of deriving the heat transfer associated with changes of its state due, for example, to chemical reactions, physical changes, or phase transitions under specified constraints. Calorimetry is performed with a calorimeter. Scottish physician and scientist Joseph Black, who was the first to recognize the distinction between heat and temperature, is said to be the founder of the science of calorimetry.

Enthalpy is the sum of a thermodynamic system's internal energy and the product of its pressure and volume. It is a state function in thermodynamics used in many measurements in chemical, biological, and physical systems at a constant external pressure, which is conveniently provided by the large ambient atmosphere. The pressure–volume term expresses the work that was done against constant external pressure to establish the system's physical dimensions from to some final volume , i.e. to make room for it by displacing its surroundings. The pressure-volume term is very small for solids and liquids at common conditions, and fairly small for gases. Therefore, enthalpy is a stand-in for energy in chemical systems; bond, lattice, solvation, and other chemical "energies" are actually enthalpy differences. As a state function, enthalpy depends only on the final configuration of internal energy, pressure, and volume, not on the path taken to achieve it.

In thermodynamics, the specific heat capacity of a substance is the amount of heat that must be added to one unit of mass of the substance in order to cause an increase of one unit in temperature. It is also referred to as massic heat capacity or as the specific heat. More formally it is the heat capacity of a sample of the substance divided by the mass of the sample. The SI unit of specific heat capacity is joule per kelvin per kilogram, J⋅kg−1⋅K−1. For example, the heat required to raise the temperature of 1 kg of water by 1 K is 4184 joules, so the specific heat capacity of water is 4184 J⋅kg−1⋅K−1.

In thermodynamics, the enthalpy of vaporization, also known as the (latent) heat of vaporization or heat of evaporation, is the amount of energy (enthalpy) that must be added to a liquid substance to transform a quantity of that substance into a gas. The enthalpy of vaporization is a function of the pressure and temperature at which the transformation takes place.

A calorimeter is a device used for calorimetry, or the process of measuring the heat of chemical reactions or physical changes as well as heat capacity. Differential scanning calorimeters, isothermal micro calorimeters, titration calorimeters and accelerated rate calorimeters are among the most common types. A simple calorimeter just consists of a thermometer attached to a metal container full of water suspended above a combustion chamber. It is one of the measurement devices used in the study of thermodynamics, chemistry, and biochemistry.

In chemistry and thermodynamics, the standard enthalpy of formation or standard heat of formation of a compound is the change of enthalpy during the formation of 1 mole of the substance from its constituent elements in their reference state, with all substances in their standard states. The standard pressure value p⦵ = 105 Pa(= 100 kPa = 1 bar) is recommended by IUPAC, although prior to 1982 the value 1.00 atm (101.325 kPa) was used. There is no standard temperature. Its symbol is ΔfH⦵. The superscript Plimsoll on this symbol indicates that the process has occurred under standard conditions at the specified temperature (usually 25 °C or 298.15 K).

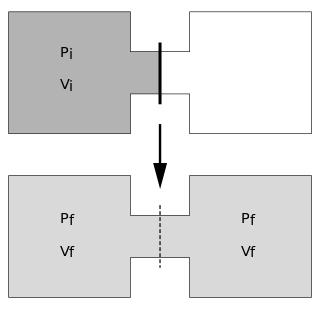

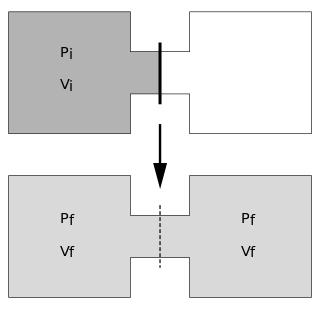

In thermodynamics, the Joule–Thomson effect describes the temperature change of a real gas or liquid when it is expanding; typically caused by the pressure loss from flow through a valve or porous plug while keeping it insulated so that no heat is exchanged with the environment. This procedure is called a throttling process or Joule–Thomson process. The effect is purely an effect due to deviation from ideality, as any ideal gas has no JT effect.

Heat capacity or thermal capacity is a physical property of matter, defined as the amount of heat to be supplied to an object to produce a unit change in its temperature. The SI unit of heat capacity is joule per kelvin (J/K).

In chemistry and thermodynamics, the enthalpy of neutralization is the change in enthalpy that occurs when one equivalent of an acid and a base undergo a neutralization reaction to form water and a salt. It is a special case of the enthalpy of reaction. It is defined as the energy released with the formation of 1 mole of water. When a reaction is carried out under standard conditions at the temperature of 298 K and 1 atm of pressure and one mole of water is formed, the heat released by the reaction is called the standard enthalpy of neutralization.

In thermodynamics, the Gibbs free energy is a thermodynamic potential that can be used to calculate the maximum amount of work, other than pressure-volume work, that may be performed by a thermodynamically closed system at constant temperature and pressure. It also provides a necessary condition for processes such as chemical reactions that may occur under these conditions. The Gibbs free energy is expressed asWhere:

The internal energy of a thermodynamic system is the energy of the system as a state function, measured as the quantity of energy necessary to bring the system from its standard internal state to its present internal state of interest, accounting for the gains and losses of energy due to changes in its internal state, including such quantities as magnetization. It excludes the kinetic energy of motion of the system as a whole and the potential energy of position of the system as a whole, with respect to its surroundings and external force fields. It includes the thermal energy, i.e., the constituent particles' kinetic energies of motion relative to the motion of the system as a whole. The internal energy of an isolated system cannot change, as expressed in the law of conservation of energy, a foundation of the first law of thermodynamics. The notion has been introduced to describe the systems characterized by temperature variations, temperature being added to the set of state parameters, the position variables known in mechanics, in a similar way to potential energy of the conservative fields of force, gravitational and electrostatic. Internal energy changes equal the algebraic sum of the heat transferred and the work done. In systems without temperature changes, potential energy changes equal the work done by/on the system.

The standard enthalpy of reaction for a chemical reaction is the difference between total product and total reactant molar enthalpies, calculated for substances in their standard states. The value can be approximately interpreted in terms of the total of the chemical bond energies for bonds broken and bonds formed.

The Clausius–Clapeyron relation, in chemical thermodynamics, specifies the temperature dependence of pressure, most importantly vapor pressure, at a discontinuous phase transition between two phases of matter of a single constituent. It is named after Rudolf Clausius and Benoît Paul Émile Clapeyron. However, this relation was in fact originally derived by Sadi Carnot in his Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire, which was published in 1824 but largely ignored until it was rediscovered by Clausius, Clapeyron, and Lord Kelvin decades later. Kelvin said of Carnot's argument that "nothing in the whole range of Natural Philosophy is more remarkable than the establishment of general laws by such a process of reasoning."

In thermodynamics, the cryoscopic constant, Kf, relates molality to freezing point depression. It is the ratio of the latter to the former:

The Joule expansion is an irreversible process in thermodynamics in which a volume of gas is kept in one side of a thermally isolated container, with the other side of the container being evacuated. The partition between the two parts of the container is then opened, and the gas fills the whole container.

The Van 't Hoff equation relates the change in the equilibrium constant, Keq, of a chemical reaction to the change in temperature, T, given the standard enthalpy change, ΔrH⊖, for the process. The subscript means "reaction" and the superscript means "standard". It was proposed by Dutch chemist Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff in 1884 in his book Études de Dynamique chimique.

In chemical thermodynamics, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) is a physical technique used to determine the thermodynamic parameters of interactions in solution. It is most often used to study the binding of small molecules to larger macromolecules in a label-free environment. It consists of two cells which are enclosed in an adiabatic jacket. The compounds to be studied are placed in the sample cell, while the other cell, the reference cell, is used as a control and contains the buffer in which the sample is dissolved.

In thermodynamics, the enthalpy of mixing is the enthalpy liberated or absorbed from a substance upon mixing. When a substance or compound is combined with any other substance or compound, the enthalpy of mixing is the consequence of the new interactions between the two substances or compounds. This enthalpy, if released exothermically, can in an extreme case cause an explosion.

In thermodynamics, heat is energy in transfer between a thermodynamic system and its surroundings by modes other than thermodynamic work and transfer of matter. Such modes are microscopic, mainly thermal conduction, radiation, and friction, as distinct from the macroscopic modes, thermodynamic work and transfer of matter. For a closed system, the heat involved in a process is the difference in internal energy between the final and initial states of a system, and subtracting the work done in the process. For a closed system, this is the formulation of the first law of thermodynamics.

In thermodynamics, the enthalpy of fusion of a substance, also known as (latent) heat of fusion, is the change in its enthalpy resulting from providing energy, typically heat, to a specific quantity of the substance to change its state from a solid to a liquid, at constant pressure.