Canadian idealism is a Canadian philosophical tradition that stemmed from British idealism.

The early idealists include George Paxton Young (1818–1889) [1] who began teaching at Knox College in 1851, Samuel Dyde (1862–1947), [2] and John Watson (1847–1939) who began teaching at Queen's University in 1872. [3] In the early 20th century, one finds Rupert Lodge (1886–1961), from the University of Manitoba, John Macdonald (1888–1972), from the University of Alberta, and Jacob Gould Schurman (1854–1942), born in Prince Edward Island, and who taught at Acadia, Dalhousie, and Cornell universities. More recent idealists include the philosophers George Grant (1918–1988), Leslie Armour (1931–2014), and Charles Taylor (born 1931). [4] James Doull (1918–2001) also developed Hegelian idealist tenets among Canadians including a philosophy of history and freedom. Both the British and Canadian idealists draw from Georg W. F. Hegel's absolute idealism, though also from Kant, Plato, and Aristotle. [ citation needed ]

In addition to the impact of idealism on Canadian political philosophy, there was a significant influence on religion in Canada, and a number of the figures who advocated for and were involved in the creation of the United Church of Canada, such as S.W. Dyde, T.B. Kilpatrick, [5] and John Watson were followers of idealist philosophy. [6]

Upon reading Canadian Idealism and the Philosophy of Freedom, former Leader of the Opposition, and former leader of the New Democratic Party, Jack Layton has described how much it influenced his thinking. [7] [8]

There are three pillars to this philosophy.

The first pillar is the response to the materialism of the Enlightenment . Idealists argue that the scientific reason of the Enlightenment artificially suppresses a significant dimension of human experience; that is, the cultural framework and historically inherited ideas with which we make sense of the world around us. Idealists hold that knowledge and reason are socially cultivated, not only with our contemporaries but also with our history. [9]

The second pillar is the philosophy of history. For idealists, philosophy includes a study of history. To reflect on what we currently believe we must understand the historical dialogue and the conflict of ideas that has brought us to this point. A wide range of subjects from economic rights to the notion of the family come into consideration, but the central question of idealists is how to reconcile civic unity (or the common good) with individual freedom. [10]

The third pillar is the formulation of a philosophy of freedom. The concept of culturally embedded knowledge and the historical approach to philosophy set the groundwork for idea of freedom as something that is achieved through a commitment to the community rather than in opposition to it, as is the case with the contract theory of Thomas Hobbes and John Locke for whom freedom is the absence of external interference with our choices (negative liberty). Freedom for the idealists is achieved through the ethical life of our community, not despite it. By participating in our society, engaging in dialogues with others about our proper ends, and giving and receiving the recognition of others that we are free, we cultivate the elements that make us self-governing (or autonomous) individuals, and hence truly free (positive liberty). [11]

Idealism in philosophy, also known as philosophical idealism or metaphysical idealism, is the set of metaphysical perspectives asserting that, most fundamentally, reality is equivalent to mind, spirit, or consciousness; that reality is entirely a mental construct; or that ideas are the highest type of reality or have the greatest claim to being considered "real". Because there are different types of idealism, it is difficult to define the term uniformly.

In the 19th century, the philosophers of the 18th-century Enlightenment began to have a dramatic effect on subsequent developments in philosophy. In particular, the works of Immanuel Kant gave rise to a new generation of German philosophers and began to see wider recognition internationally. Also, in a reaction to the Enlightenment, a movement called Romanticism began to develop towards the end of the 18th century. Key ideas that sparked changes in philosophy were the fast progress of science, including evolution, most notably postulated by Charles Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, and theories regarding what is today called emergent order, such as the free market of Adam Smith within nation states, or the Marxist approach concerning class warfare between the ruling class and the working class developed by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Pressures for egalitarianism, and more rapid change culminated in a period of revolution and turbulence that would see philosophy change as well.

German idealism is a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutionary politics of the Enlightenment. The period of German idealism after Kant is also known as post-Kantian idealism or simply post-Kantianism. One scheme divides German idealists into transcendental idealists, associated with Kant and Fichte, and absolute idealists, associated with Schelling and Hegel.

Charles Margrave Taylor is a Canadian philosopher from Montreal, Quebec, and professor emeritus at McGill University best known for his contributions to political philosophy, the philosophy of social science, the history of philosophy, and intellectual history. His work has earned him the Kyoto Prize, the Templeton Prize, the Berggruen Prize for Philosophy, and the John W. Kluge Prize.

A subset of absolute idealism, British idealism was a philosophical movement that was influential in Britain from the mid-nineteenth century to the early twentieth century. The leading figures in the movement were T. H. Green (1836–1882), F. H. Bradley (1846–1924), and Bernard Bosanquet (1848–1923). They were succeeded by the second generation of J. H. Muirhead (1855–1940), J. M. E. McTaggart (1866–1925), H. H. Joachim (1868–1938), A. E. Taylor (1869–1945), and R. G. Collingwood (1889–1943). The last major figure in the tradition was G. R. G. Mure (1893–1979). Doctrines of early British idealism so provoked the young Cambridge philosophers G. E. Moore and Bertrand Russell that they began a new philosophical tradition, analytic philosophy.

George Parkin Grant was a Canadian philosopher, university professor and social critic. He is known for his Canadian nationalism, a political conservatism that affirms the values of community, equality and justice and his critical, philosophical analysis of the social and political effects of limitless technological progress. As a practising Christian, Grant conceived of time as the moving image of an eternal order illuminated by love.

Modern philosophy is philosophy developed in the modern era and associated with modernity. It is not a specific doctrine or school, although there are certain assumptions common to much of it, which helps to distinguish it from earlier philosophy.

Absolute idealism is chiefly associated with Friedrich Schelling and G. W. F. Hegel, both of whom were German idealist philosophers in the 19th century. The label has also been attached to others such as Josiah Royce, an American philosopher who was greatly influenced by Hegel's work, and the British idealists.

Canadian nationalism seeks to promote the unity, independence, and well-being of Canada and the Canadian people. Canadian nationalism has been a significant political force since the 19th century and has typically manifested itself as seeking to advance Canada's independence from influence of the United Kingdom and the United States. Since the 1960s, most proponents of Canadian nationalism have advocated a civic nationalism due to Canada's cultural diversity that specifically has sought to equalize citizenship, especially for Québécois and other French-speaking Canadians, who historically faced cultural and economic discrimination and assimilationist pressure from English Canadian-dominated governments. Canadian nationalism became an important issue during the 1988 Canadian federal election that focused on the then-proposed Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement, with Canadian nationalists opposing the agreement – saying that the agreement would lead to inevitable complete assimilation and domination of Canada by the United States. During the 1995 Quebec referendum to determine whether Quebec would become a sovereign state or whether it would remain in Canada, Canadian nationalists and federalists supported the "no" side while Quebec nationalists largely supported the "yes" side, resulting in a razor-thin majority in favour of the "no" side.

William Sweet is a Canadian philosopher, and a past president of the Canadian Philosophical Association and of the Canadian Theological Society.

This is a bibliography of major works on the History of Canada.

Crawford Brough Macpherson was an influential Canadian political scientist who taught political theory at the University of Toronto.

Alfred Edward Taylor, usually cited as A. E. Taylor, was a British idealist philosopher most famous for his contributions to the philosophy of idealism in his writings on metaphysics, the philosophy of religion, moral philosophy, and the scholarship of Plato. He was a fellow of the British Academy (1911) and president of the Aristotelian Society from 1928 to 1929. At Oxford he was made an honorary fellow of New College in 1931. In an age of universal upheaval and strife, he was a notable defender of Idealism in the Anglophone world.

The study and teaching of philosophy in Canada date from the time of New France. Generally, Canadian philosophers have not developed unique forms of philosophical thought; rather, Canadian philosophers have reflected particular views of established European and later American schools of philosophical thought, be it Thomism, Objective Idealism, or Scottish Common Sense Realism. Since the mid-twentieth century the depth and scope of philosophical activity in Canada has increased dramatically. This article focuses on the evolution of epistemology, logic, the philosophy of mind, metaphysics, ethics and metaethics, and continental philosophy in Canada.

Challenge for Change was a participatory film and video project created by the National Film Board of Canada in 1967, the Canadian Centennial. Active until 1980, Challenge for Change used film and video production to illuminate the social concerns of various communities within Canada, with funding from eight different departments of the Canadian government. The impetus for the program was the belief that film and video were useful tools for initiating social change and eliminating poverty. As Druik says, "The new program, which was developed in tandem with the new social policies, was based on the argument that participation in media projects could empower disenfranchised groups and that media representation might effectively bring about improved political representation." Stewart, quoting Jones (1981) states "the Challenge for Change films would convey messages from 'the people' to the government, directly or through the Canadian public."

This is a bibliography of works on Canada.

This is a bibliography of works on the military history of Canada.

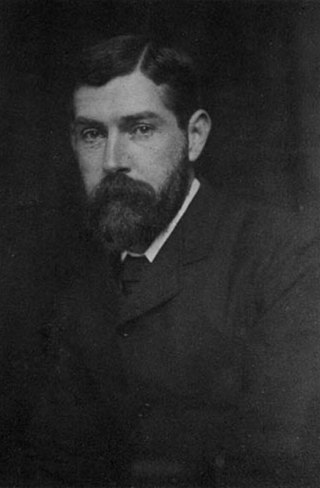

John Watson was a Canadian philosopher and academic.

Richard Vernon is a Canadian academic and from 1981 he has been Professor of Political Science at the University of Western Ontario.