Lyperosomum intermedium is a parasitic trematode belonging to the subclass Digenea that infects the marsh rice rat. The species was first described in 1972 by Denton and Kinsella, who wrote that it was closest to Lyperosomum sinuosum, known from birds and raccoons in the United States and Brazil. Three years later, Denton and Kissinger placed the two, together with a number of other species, in a new subgenus of Lyperosomum, Sinuosoides. Species of Lyperosomum mainly infect birds; L. intermedium is one of the few species to infect a mammal.

Notocotylus fosteri is a parasitic fluke that infects the marsh rice rat in Florida.

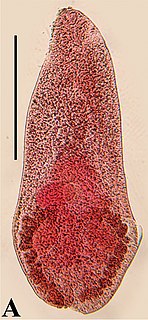

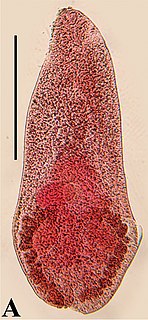

Maritrema heardi is a parasitic fluke that infects the marsh rice rat in a salt marsh at Cedar Key, Florida. It was first listed as Maritrema sp. II in 1988, then described as the only species of a new genus, Floridatrema heardi, in 1994, and eventually reassigned in 2003 to Maritrema as Maritrema heardi. Its intermediate host is the fiddler crab Uca pugilator and it lives in the intestine of the marsh rice rat, its definitive host. Together with two other species of Maritrema, it is very common in affected marsh rice rats; it infects 19% of studied rats at Cedar Key. According to Tkach and colleagues, M. heardi is probably primarily a parasite of birds that has secondarily infected the marsh rice rat. Floridatrema was distinguished from Maritrema on the basis of its possession of loops of the uterus that extend forward to the place where the intestine is forked or even to the pharynx. Genetically, M. heardi may be closest to the morphologically similar M. neomi, which infects Neomys water shrews in the Carpathians.

Aonchotheca forresteri is a parasitic nematode that infects the marsh rice rat in Florida. Occurring mainly in adults, it inhabits the stomach. It is much more common during the wet season, perhaps because its unknown intermediate host is an earthworm that only emerges when it rains. The worm was discovered in 1970 and formally described in 1987. Originally classified in the genus Capillaria, it was reclassified in Aonchotheca in 1999. A. forresteri is small and narrow-bodied, with a length of 13.8 to 19.4 mm in females and 6.8 to 9.2 mm in males. Similar species such as A. putorii differ in features of the alae and spicule, the size of the female, and the texture of the eggs.

Ascocotyle angrense is a fluke in the genus Ascocotyle that mainly infects birds. It has previously been confused with A. diminuta, which infects fish-eating birds and raccoons. It has also been recorded from the marsh rice rat in a saltwater marsh at Cedar Key, Florida, where it occurred in 25% of animals.

Ascocotyle pindoramensis is a fluke in the genus Ascocotyle that occurs along the eastern coast of the Americas from Brazil to Nicaragua, Mexico, Louisiana, and Florida and doubtfully in Egypt. It occurs in the intestine of its definitive hosts. Hosts recorded in the wild include the least bittern, roseate spoonbill, great blue heron, striated heron, stripe-backed bittern, yellow-crowned night heron, black-crowned night heron, osprey, Neotropic cormorant, and marsh rice rat. In the marsh rice rat, it infected 9% of rats examined in a 1970–1972 study in the salt marsh at Cedar Key, Florida, but none in a freshwater marsh. A. pindoramensis has been experimentally introduced into the domestic duck, chicken, dog, house mouse, and golden hamster. It occurs in various body parts of its intermediate hosts—the poeciliid fish Phalloptychus januarius, Poecilia catemaconis, Poecilia mexicana, Poecilia mollienisicola, Poecilia vivipara, and a species of Xiphophorus and the cichlid Tilapia. It was first described as Pygidiopsis pindoramensis in 1928 and subsequently as Pseudoascocotyle mollienisicola in 1960. The latter species was moved to Ascocotyle in 1963, but only in 2006 it was recognized that the two represent the same species, which is now known as Ascocotyle pindoramensis. Other flukes from Argentina and Mexico that were identified as Pygidiopsis pindoramensis instead represent a different species of Pygidiopsis.

Brachylaima virginianum is a fluke of the genus Brachylaima that infects the Virginia opossum throughout its range. It has also been found in young black bears and in marsh rice rats, both from Florida., and from raccoons in Kentucky.

Echinochasmus schwartzi is a fluke that infects dogs, muskrats, and marsh rice rats. It uses Fundulus fish as its intermediate host. Adults are similar to Echinochasmus microcaudatus, but differ in features of the oral sucker.

Fibricola lucida is a fluke that infects Virginia opossums, American minks, and marsh rice rats in North America. In a study in Florida, F. lucida was the only fluke of the marsh rice rat that occurred in both the freshwater marsh at Paynes Prairie and the saltwater marsh at Cedar Key. At the former locality, it infected 11% of rice rats and the number of worms per infected rat ranged from 1 to 65, averaging 17. At Cedar Key, 67% of rice rats were infected and the number of worms per infected rat ranged from 1 to 1975, averaging 143.

Gynaecotyla adunca is a fluke that normally infects birds. It has also been found in 15% of a sample of the marsh rice rat from a salt marsh at Cedar Key, Florida. It uses fiddler crabs such as Uca rapax as its intermediate host.

Maritrema is a genus of trematodes (flukes) in the family Microphallidae, although some have suggested its placement in the separate family Maritrematidae. It was first described by Nikoll in 1907 from birds in Britain. Species of the genus usually infect birds, but several have switched hosts and are found in mammals, such as the marsh rice rat. Several species use the fiddler crab Uca pugilator as an intermediate host.

Microphallus nicolli is a species of digenean parasite in the genus Microphallus. Recorded hosts include the marsh rice rat in a saltmarsh at Cedar Key, Florida, where the crab Eurytium limosum is an intermediate host, and the sea otter in central California. It was previously known as Spelotrema nicolli.

Odhneria odhneri is a digenean parasite in the genus Odhneria of family Microphallidae. It infects several species of shorebirds, including the willet, as well as the marsh rice rat.

Probolocoryphe glandulosa is a digenean parasite in the genus Probolocoryphe of family Microphallidae. Recorded hosts include the clapper rail, ruddy turnstone, raccoon, little blue heron, Wilson's plover, black-bellied plover, and marsh rice rat.

Acanthotrema cursitans is a species of fluke in the genus Acanthotrema. It infects the marsh rice rat Oryzomys palustris, the raccoon Procyon lotor, the Virginia opossum Didelphis virginiana, the snail Cerithidea scalariformis, and killifishes of the genus Fundulus on the Gulf Coast of Florida. It was first described as Cercaria cursitans in 1961, then moved to Stictodora in 1974, and to Acanthotrema in 2003.

Urotrema scabridum is a fluke in the genus Urotrema of family Urotrematidae. Recorded hosts include:

Capillaria gastrica is a parasitic nematode in the genus Capillaria. Among the known host species are the marsh rice rat and deermouse.

Litomosoides scotti is a parasitic nematode in the genus Litomosoides. First described in 1973, it infects the marsh rice rat and is known from a saltwater marsh at Cedar Key, Florida.

Parastrongylus schmidti is a species of parasitic nematode in the genus Parastrongylus. It was first described as Angiostrongylus schmidti in 1971 from the marsh rice rat in Florida, but later assigned to Parastrongylus.