Context

The poem is about the self-mutilation and subsequent lament of Attis, a priest of Cybele. [1] The centre of the worship of the Phrygian Κυβέλη or Κυβήβη, was in very ancient times the town of Pessinus in Galatian Phrygia, at the foot of Mount Dindymus, from which the goddess received the name Dindymene. [1] Cybele had early become identified with the Cretan divinity Rhea, the Mother of the Gods, and to some extent with Demeter, the search of Cybele for Attis being compared with that of Demeter for Persephone. [1] The especial worship of Cybele was conducted by emasculated priests called Galli (or, with reference to their physical condition, Gallae). [lower-alpha 1] [1] Their name was derived by the ancients from that of the river Gallus, a tributary of the Sangarius, by drinking from which men became inspired with frenzy. [lower-alpha 2] [1] The worship was orgiastic in the extreme, and was accompanied by the sound of such frenzy-producing instruments as the tympana, cymbala, tibiae, and cornu, and culminated in scourging, self-mutilation, syncope from excitement, and even death from hemorrhage or heart-failure. [lower-alpha 3] [1] The worship of the Magna Mater, or Mater Idaea, as she was often called (perhaps from identification with Rhea of the Cretan Mount Ida rather than from the Trojan Mount Ida), was introduced into Rome in 205 BC. [1] in accordance with a Sibylline oracle which foretold that only so could 'a foreign enemy' (i.e. Hannibal) be driven from Italy. [1] Livy gives an interesting account of the solemnities that accompanied the transfer from Pessinus to Rome of the black stone that represented the divinity, and of the establishment of the Megalensia. [lower-alpha 4] [2] The stone itself was perhaps a meteorite, and is thus described by one Latin source: lapis quidam non magnus, ferri manu hominis sine ulla impressione qui posset; coloris furvi atque atri, angellis prominentibus inaequalis, et quem omnes hodie … videmus … indolatum et asperum. [lower-alpha 5] [3] Servius speaks of it as acus Matris Deum, and as one of the seven objects on which depended the safety of Rome. [lower-alpha 6] [3]

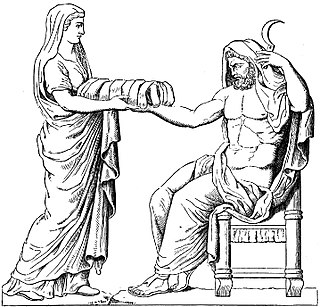

According to E. T. Merrill, the early connection of Attis with the Mother of the Gods seems to point to the association of an original male element with an original female element as the parents of all things. [3] But in the age of tradition Attis appears as a servant instead of an equal, and the subordination of the male to the female element is further emphasized by the representation of Attis, like the Galli of historic times, as an emasculated priest. [3] Greek imagination pictured him as a beautiful youth who was beloved by the goddess, but wandered away from her and became untrue; but being sought and recalled to allegiance by her, in a passion of remorse he not only spent his life in her service, but by his own act made impossible for the future such infidelity on his part, thus setting the example followed by all the Galli after him. [lower-alpha 7] [3]