Read, Charles Hercules, & Dalton, Ormonde Maddock (1899). Antiquities from the city of Benin and from other parts of West Africa in the British Museum. London: British Museum.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)Notes

- ↑ Balfour, 61

- ↑ Balfour, 61

- ↑ Balfour, 61; Tonnochy, 84–85; Burlington, 153

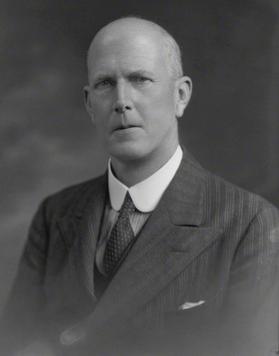

- ↑ Raymond John Howgego, 'Joyce, Thomas Athol (1878–1942)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, May 2010 accessed 1 Dec 2013

- ↑ Tonnochy, 83, 86

- ↑ Balfour, 61; Tonnochy, 85; Burlington, 153–154

- ↑ David Mackenzie Wilson (1964), Catalogue of antiquities of the later Saxon period, British Museum, OCLC 610435306,

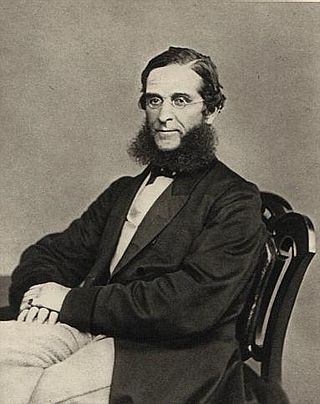

The brooch's history (as recounted by Bruce-Mitford) is that it was bought from a London bric-à-brac dealer by an unnamed man who did not know its history, he passed it to Sir Charles Robinson who published it in 'The Antiquary'. A few years later Mr. E. Hockliffe, the son-in-law of Sir Charles Robinson, offered the brooch as a loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. E. T. Leeds, then an assistant at the museum, persuaded the then keeper D. G. Hogarth to accept the loan. On the advice of the then Keeper of British and Medieval Antiquities at the British Museum (Sir Hercules Read, P.S.A.) and his assistant keeper (R. A. Smith) the brooch was pronounced a fake and withdrawn from exhibition with the approval of the Ashmolean Museum's technical specialist, W. H. Young. The brooch was eventually purchased by Capt. A. W. F. Fuller and, apart from occasional mentions (e.g. by Sir Alfred Clapham), was not thought of seriously until the Strickland brooch (registration no. 1949,0702.1) was brought to the British Museum. On the advice of Sir Thomas Kendrick the Fuller brooch was traced by Mr. Bruce-Mitford and after laboratory examination it was acquired by the British Museum.

- ↑ Tonnochy, 86

Related Research Articles

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology on Beaumont Street, Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University of Oxford in 1677. It is also the world's second university museum, after the establishment of the Kunstmuseum Basel in 1661 by the University of Basel.

Sutton Hoo is the site of two Anglo-Saxon cemeteries dating from the 6th to 7th centuries near Woodbridge, Suffolk, England. Archaeologists have been excavating the area since 1938, when an undisturbed ship burial containing a wealth of Anglo-Saxon artifacts was discovered. The site is important in establishing the history of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of East Anglia as well as illuminating the Anglo-Saxons during a period which lacks historical documentation.

The Fuller Brooch is an Anglo-Saxon silver and niello brooch dated to the late 9th century, which is now in the British Museum, where it is normally on display in Room 41. The elegance of the engraved decoration depicting the Five Senses, highlighted by being filled with niello, makes it one of the most highly regarded pieces of Anglo-Saxon art.

Sir John Evans was an English antiquarian, geologist and founder of prehistoric archaeology.

The Alfred Jewel is a piece of Anglo-Saxon goldsmithing work made of enamel and quartz enclosed in gold. It was discovered in 1693, in North Petherton, Somerset, England and is now one of the most popular exhibits at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. It has been dated to the late 9th century, in the reign of Alfred the Great, and is inscribed "AELFRED MEC HEHT GEWYRCAN", meaning "Alfred ordered me made". The jewel was once attached to a rod, probably of wood, at its base. After decades of scholarly discussion, it is now "generally accepted" that the jewel's function was to be the handle for a pointer stick for following words when reading a book. It is an exceptional and unusual example of Anglo-Saxon jewellery.

Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks was a British antiquarian and museum administrator. Franks was described by Marjorie Caygill, historian of the British Museum, as "arguably the most important collector in the history of the British Museum, and one of the greatest collectors of his age."

The Benty Grange helmet is an Anglo-Saxon boar-crested helmet from the seventh century AD. It was excavated by Thomas Bateman in 1848 from a tumulus at the Benty Grange farm in Monyash in western Derbyshire. The grave had probably been looted by the time of Bateman's excavation, but still contained other high-status objects suggestive of a richly furnished burial, such as the fragmentary remains of a hanging bowl. The helmet is displayed at Sheffield's Weston Park Museum, which purchased it from Bateman's estate in 1893.

Sir Thomas Downing Kendrick was a British archaeologist and art historian.

Rupert Leo Scott Bruce-Mitford was a British archaeologist and scholar. He spent the majority of his career at the British Museum, primarily as the Keeper of the Department of British and Medieval Antiquities, and was particularly known for his work on the Sutton Hoo ship-burial. Considered the "spiritus rector" of such research, he oversaw the production of the monumental three-volume work The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial, termed by the president of the Society of Antiquaries as "one of the great books of the century".

The Sylloge of the Coins of the British Isles (SCBI) is an ongoing project to publish all major museum collections and certain important private collections of British coins. Catalogues in the series contain full details and illustrations of each and every specimen. Every Anglo-Saxon and Norman coin included in the project can be viewed on the SCBI Database, based at the Department of Coins and Medals, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

Reginald Allender Smith was an archaeologist of Palaeolithic to late Anglo-Saxon materials. He was Keeper of British and Medieval Antiquities at the British Museum from 1927-1938, and authored several books and British Museum catalogues.

The Sutton Hoo helmet is a decorated Anglo-Saxon helmet found during a 1939 excavation of the Sutton Hoo ship-burial. It was buried around the years c. 620–625 CE and is widely associated with an Anglo-Saxon leader, King Rædwald of East Anglia; its elaborate decoration may have given it a secondary function akin to a crown. The helmet was both a functional piece of armour and a decorative piece of metalwork. An iconic object from an archaeological find hailed as the "British Tutankhamen", it has become a symbol of the Early Middle Ages, "of Archaeology in general", and of England.

Ethnography at the British Museum describes how ethnography has developed at the British Museum.

Edward Thurlow Leeds was an English archaeologist and museum curator. He was Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum from 1928 to 1945.

William Buller Fagg was a British curator and anthropologist. He was the Keeper of the Department of Ethnography at the British Museum (1969–1974), and pioneering historian of Yoruba and Nigerian art, with a particular focus on the art of Benin.

Ormonde Maddock Dalton, FBA (1866–1945) was a British museum curator and archaeologist. Though very much an all-rounder, his main expertise was in medieval art. He usually published as O. M. Dalton, but also wrote under the pseudonym W. Compton Leith.

Herbert James Maryon was an English sculptor, conservator, goldsmith, archaeologist and authority on ancient metalwork. Maryon practiced and taught sculpture until retiring in 1939, then worked as a conservator with the British Museum from 1944 to 1961. He is best known for his work on the Sutton Hoo ship-burial, which led to his appointment as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire.

Robert Lockhart Hobson CB was a British civil servant and antiquarian. He was keeper of the Department of Ceramics and Ethnography at the British Museum and an authority on Far Eastern ceramics. He was noted for his cataloguing which The Times described as establishing firm facts for what had previously been "surmise and unproved tradition" and he was highly influential through his writing in the elevation of Chinese ceramics from craft works to the status of objects of fine art. He was president of the Oriental Ceramic Society from 1939 to 1942.

The Benty Grange hanging bowl is a fragmentary Anglo-Saxon artifact from the seventh century AD. All that remains are parts of two escutcheons: bronze frames that are usually circular and elaborately decorated, and that sit along the outside of the rim or at the interior base of a hanging bowl. A third one disintegrated soon after excavation, and it no longer survives. The escutcheons were found in 1848 by the antiquary Thomas Bateman, while excavating a tumulus at the Benty Grange farm in western Derbyshire. They were presumably buried as part of an entire hanging bowl. The grave had probably been looted by the time of Bateman's excavation, but still contained high-status objects suggestive of a richly furnished burial, including the hanging bowl and the boar-crested Benty Grange helmet.

References

- "Burlington": Sir Hercules Read, The Burlington Magazine (no author given), Vol. 54, No. 312 (Mar. 1929), pp. 153–154, JSTOR

- Balfour, Henry, Obituary Sir Charles Hercules Read, 6 July 1857 – 11 February 1929, Man (Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland), Vol. 29, (Apr. 1929), pp. 61–62, JSTOR

- Tonnochy, A. B., Four Keepers of the Department of British and Medieval Antiquities, The British Museum Quarterly , Vol. 18, No. 3 (Sep. 1953), pp. 83–88, JSTOR

External links

Charles Hercules Read | |

|---|---|

Bust by Henry Pegram | |

| Born | 6 July 1857 |

| Died | 11 February 1929 (aged 71) Rapallo, Italy |

| Nationality | British |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh (honorary doctorate) |

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| People | |

| Other | |