Andrei Platonovich Platonov was a Soviet Russian novelist, short story writer, philosopher, playwright, and poet. Although Platonov regarded himself as a communist, his principal works remained unpublished in his lifetime because of their skeptical attitude toward collectivization of agriculture (1929–1940) and other Stalinist policies, as well as for their experimental, avant-garde form infused with existentialism which was not in line with the dominant socialist realism doctrine. His famous works include the novels Chevengur (1928) and The Foundation Pit (1930).

Julian Alexandrovich Scriabin was a Swiss-born Russian composer and pianist who was the youngest son of Alexander Scriabin and Tatiana de Schloezer.

The Catacomb Church as a collective name labels those representatives of the Russian Orthodox clergy, laity, communities, monasteries, brotherhoods, etc., who for various reasons, moved to an illegal position from the 1920s onwards. In a narrow sense, the term "catacomb church" means not just illegal communities, but communities that rejected subordination to the acting patriarchal locum tenens Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky) after 1927, and that adopted anti-Soviet positions. During the Cold War of 1947-1991 the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia popularized the term in the latter sense, first within the Russian diaspora, and then in the USSR. The expression "True Orthodox church" is synonymous with this latter, narrower sense of "catacomb church".

Boris Sokolov, is a historian and a Russian literature researcher. In 1979 he graduated from the department of geography of the Moscow State University, specialising in economic geography. His works have been translated into Japanese, Polish, Latvian and Estonian. He has also translated literary works from various languages.

Aleksandr Vasilyevich Sukhovo-Kobylin was a Russian philosopher and playwright, chiefly known for his satirical plays criticizing Russian imperial bureaucracy. His sister Evgenia Tur was a popular novelist, critic and journalist and his sister Sofia was a painter of some note.

Eugeny Vladimirovich Pchelov is a Russian specialist in history, heraldry and genealogy. He has published several monographs on the history, such as Rurikides. History of dynasty (2001), Romanov. History of dynasty (2001), Old Russian princely genealogy (2001), State symbols of Russia: Coat of Arms, Flag, Anthem (2007) and others.

Molodaya Gvardiya is an open joint-stock Russian publishing house, one of the oldest publishers in Russia, having been founded in 1922 during the Soviet era. From 1938 until 1992, it was responsible for publishing the magazine Vokrug sveta .

Uncle's Dream is an 1859 novella by Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky. The first work of Dostoevsky after a long pause, the novella was written during the author's stay in Semipalatinsk. It was first published in the Russian magazine Russkoye Slovo.

Alexander Nikolayevich Senkevich is a Russian Indologist, philologist, translator from Hindi, writer, and poet. He is also known as Helena Blavatsky's biographer.

The House of Lopukhin was an old Russian noble family, most influential during the Russian Empire, forming one of the branches of the Sorokoumov-Glebov family.

Arina Matveyevna Sobakina, was a Russian ballerina and stage actress performing as a "comic dancer". She belonged to the pioneer group of professional stage artists in Russia.

The 7th Ukrainian Soviet Division was a military unit of the Red Army during the Russian Civil War in the armed forces of the Ukrainian SSR.

“The story of Monsieur Jourdan, a botanist and the dervish Mastalishah, a famous sorcerer” the second comedy in four acts by the Azerbaijani writer and playwright Mirza Fatali Akhundov, written in 1850 in the Azerbaijani language. It is noted that the comedy was directed against the medieval feudal ideology, against superstitions. Translated by the author into Russian, it was published in 1851 in the Kavkaz newspaper. The first production on the Russian stage, on the translation of the author, took place in the same year in St. Petersburg, in 1852 the play was staged in Tiflis, and in 1883 - in Nakhchivan.

"Pack of Cigarettes" is a song by the Soviet post-punk band Kino from the album Star Called Sun released in 1988. One of Kino's most popular songs. It was written in 1988, when Viktor Tsoi was filmed in the Needle.

Agniya Aleksandrovna Kuznetsova was a Russian Soviet children's writer.

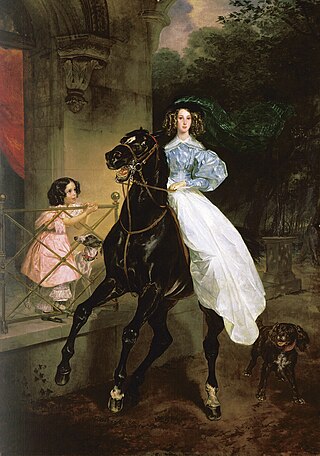

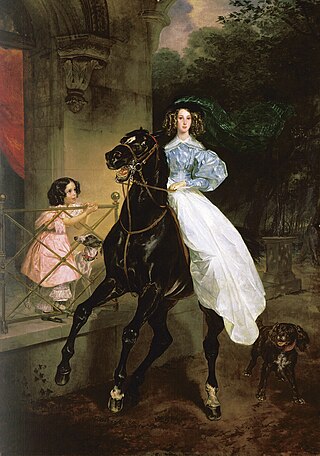

Horsewoman is a painting by the Russian artist Karl Bryullov (1799-1852), produced in 1832 and preserved in the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. The size of the canvas is 291.5 × 206 cm.

The Lives of Remarkable People is a book series containing fiction and biographical books intended for the mass audience. It was first published in 1890 till 1924 by Florenty Pavlenkov as Жизнь замечательных людей (1890—1924). It is mainly reprints of biographies published after 1900s. Since then there have been several attempts to revive the series, but only Maxim Gorky succeeded. In 1933–1938 the series was reissued by the Association of Periodicals and Newspapers, with the numbering starting from one. After 1938, the series was published by "Molodaya Gvardiya" with a continuous numbering of issues; since 2001, the numbering has been doubled. By 2010, the total number of editions exceeded one and a half thousand, and the total circulation of the series exceeded one hundred million copies.

Moscow Courtyard is a landscape painting by the Russian artist Vasily Polenov (1844–1927), completed in 1878. It belongs to the State Tretyakov Gallery. Its dimensions are 64.5 × 80.1 cm. Together with two other works by Polenov from the late 1870s: the paintings Grandmother's Garden and Overgrown Pond, the canvas Moscow Courtyard has been attributed to "a kind of lyrical and philosophical trilogy of the artist".

A Quiet Monastery is a landscape by Russian artist Isaak Levitan (1860-1900), painted in 1890. It belongs to the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. Its size is 87.5×108 cm.

Taking a Snow Town is a painting by the Russian artist Vasily Surikov (1848–1916), completed in 1891. It is kept in the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. The size of the canvas is 156×282 cm. The painting depicts the climax of an ancient folk game popular among the Siberian Cossack community. According to tradition, the game was organized on the last day of Maslenitsa, and the artist, who grew up in Krasnoyarsk, observed it many times during his childhood. Surikov worked on the canvas during his stay in Krasnoyarsk from 1889 to 1890, and finished it after his return to Moscow. Many of his relatives and acquaintances served as sitters.