Related Research Articles

Microevolution is the change in allele frequencies that occurs over time within a population. This change is due to four different processes: mutation, selection, gene flow and genetic drift. This change happens over a relatively short amount of time compared to the changes termed macroevolution.

Mendelian inheritance is a type of biological inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and later popularized by William Bateson. These principles were initially controversial. When Mendel's theories were integrated with the Boveri–Sutton chromosome theory of inheritance by Thomas Hunt Morgan in 1915, they became the core of classical genetics. Ronald Fisher combined these ideas with the theory of natural selection in his 1930 book The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection, putting evolution onto a mathematical footing and forming the basis for population genetics within the modern evolutionary synthesis.

In biology, a hybrid is the offspring resulting from combining the qualities of two organisms of different varieties, species or genera through sexual reproduction. Generally, it means that each cell has genetic material from two different organisms, whereas an individual where some cells are derived from a different organism is called a chimera. Hybrids are not always intermediates between their parents, but can show hybrid vigor, sometimes growing larger or taller than either parent. The concept of a hybrid is interpreted differently in animal and plant breeding, where there is interest in the individual parentage. In genetics, attention is focused on the numbers of chromosomes. In taxonomy, a key question is how closely related the parent species are.

Cedrus, with the common English name cedar, is a genus of coniferous trees in the plant family Pinaceae. They are native to the mountains of the western Himalayas and the Mediterranean region, occurring at altitudes of 1,500–3,200 m in the Himalayas and 1,000–2,200 m in the Mediterranean.

The gymnosperms are a group of seed-producing plants that includes conifers, cycads, Ginkgo, and gnetophytes, forming the clade Gymnospermae. The term gymnosperm comes from the composite word in Greek: γυμνόσπερμος, literally meaning 'naked seeds'. The name is based on the unenclosed condition of their seeds. The non-encased condition of their seeds contrasts with the seeds and ovules of flowering plants (angiosperms), which are enclosed within an ovary. Gymnosperm seeds develop either on the surface of scales or leaves, which are often modified to form cones, or on their own as in yew, Torreya, Ginkgo. Gymnosperm lifecycles involve alternation of generations. They have a dominant diploid sporophyte phase and a reduced haploid gametophyte phase which is dependent on the sporophytic phase. The term "gymnosperm" is often used in paleobotany to refer to all non-angiosperm seed plants. In that case, to specify the modern monophyletic group of gymnosperms, the term Acrogymnospermae is sometimes used.

Cupressaceae is a conifer family, the cypress, with worldwide distribution. The family includes 27–30 genera, which include the junipers and redwoods, with about 130–140 species in total. They are monoecious, subdioecious or (rarely) dioecious trees and shrubs up to 116 m (381 ft) tall. The bark of mature trees is commonly orange- to red-brown and of stringy texture, often flaking or peeling in vertical strips, but smooth, scaly or hard and square-cracked in some species.

Backcrossing is a crossing of a hybrid with one of its parents or an individual genetically similar to its parent, to achieve offspring with a genetic identity closer to that of the parent. It is used in horticulture, animal breeding, and production of gene knockout organisms.

An F1 hybrid (also known as filial 1 hybrid) is the first filial generation of offspring of distinctly different parental types. F1 hybrids are used in genetics, and in selective breeding, where the term F1 crossbreed may be used. The term is sometimes written with a subscript, as F1 hybrid. Subsequent generations are called F2, F3, etc.

A coywolf is a canid hybrid descended from coyotes, eastern wolves, gray wolves, and dogs. All of these species are members of the genus Canis with 78 chromosomes and therefore can interbreed. One genetic study indicates that these two species genetically diverged relatively recently. Genomic studies indicate that nearly all North American gray wolf populations possess some degree of admixture with coyotes following a geographic cline, with the lowest levels occurring in Alaska, and the highest in Ontario and Quebec, as well as Atlantic Canada. Another term for these hybrids is sometimes wolfote.

Introgression, also known as introgressive hybridization, in genetics is the transfer of genetic material from one species into the gene pool of another by the repeated backcrossing of an interspecific hybrid with one of its parent species. Introgression is a long-term process, even when artificial; it may take many hybrid generations before significant backcrossing occurs. This process is distinct from most forms of gene flow in that it occurs between two populations of different species, rather than two populations of the same species.

The mechanisms of reproductive isolation are a collection of evolutionary mechanisms, behaviors and physiological processes critical for speciation. They prevent members of different species from producing offspring, or ensure that any offspring are sterile. These barriers maintain the integrity of a species by reducing gene flow between related species.

Cytoplasmic male sterility is total or partial male sterility in hermaphrodite organisms, as the result of specific nuclear and mitochondrial interactions. Male sterility is the failure to produce functional anthers, pollen, or male gametes. Such male sterility in hermaphrodite populations leads to gynodioecious populations.

A doubled haploid (DH) is a genotype formed when haploid cells undergo chromosome doubling. Artificial production of doubled haploids is important in plant breeding.

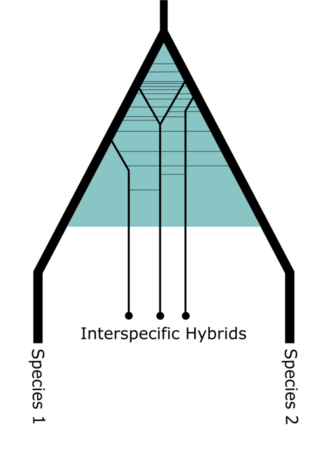

A hybrid swarm is a population of hybrids that has survived beyond the initial hybrid generation, with interbreeding between hybrid individuals and backcrossing with its parent types. Such population are highly variable, with the genetic and phenotypic characteristics of individuals ranging widely between the two parent types. Hybrid swarms thus blur the boundary between the parent taxa. Precise definitions of which populations can be classified as hybrid swarms vary, with some specifying simply that all members of a population should be hybrids, while others differ in whether all members should have the same or different levels of hybridization.

Perennial rice are varieties of long-lived rice that are capable of regrowing season after season without reseeding; they are being developed by plant geneticists at several institutions. Although these varieties are genetically distinct and will be adapted for different climates and cropping systems, their lifespan is so different from other kinds of rice that they are collectively called perennial rice. Perennial rice—like many other perennial plants—can spread by horizontal stems below or just above the surface of the soil but they also reproduce sexually by producing flowers, pollen and seeds. As with any other grain crop, it is the seeds that are harvested and eaten by humans.

Sequoioideae, commonly referred to as redwoods, is a subfamily of coniferous trees within the family Cupressaceae. It includes the largest and tallest trees in the world. The subfamily achieved its maximum diversity during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods.

Citrus taxonomy refers to the botanical classification of the species, varieties, cultivars, and graft hybrids within the genus Citrus and related genera, found in cultivation and in the wild.

Eukaryote hybrid genomes result from interspecific hybridization, where closely related species mate and produce offspring with admixed genomes. The advent of large-scale genomic sequencing has shown that hybridization is common, and that it may represent an important source of novel variation. Although most interspecific hybrids are sterile or less fit than their parents, some may survive and reproduce, enabling the transfer of adaptive variants across the species boundary, and even result in the formation of novel evolutionary lineages. There are two main variants of hybrid species genomes: allopolyploid, which have one full chromosome set from each parent species, and homoploid, which are a mosaic of the parent species genomes with no increase in chromosome number.

Introgressive hybridization, also known as introgression, is the flow of genetic material between divergent lineages via repeated backcrossing. In plants, this backcrossing occurs when an generation hybrid breeds with one or both of its parental species.

Hybridization, when new offspring arise from crosses between individuals of the same or different species, results in the assemblage of diverse genetic material and can act as a stimulus for evolution. Hybrid species are often more vigorous and genetically differed than their ancestors. There are primarily two different forms of hybridization: natural hybridization in an uncontrolled environment, whereas artificial hybridization occurs primarily for the agricultural purposes.

References

- ↑ Rieseberg. L. H. and Soltis, D. E. (1991) Phylogenetic consequences of cytoplasmic gene flow in plants Archived 2010-09-28 at the Wayback Machine . Evolutionary Trends in Plants 5: 65-84

- ↑ Terry RG, Nowak RS, Tausch (2000) Genetic variation in chloroplast and nuclear ribosomal DNA in Utah juniper ( Juniperus osteosperma, Cupressaceae): evidence for interspecific gene flow. American Journal of Botany 87: 250-258

- ↑ Matos, J. A. and B. A. Schaal. 2000. Chloroplast evolution in the Pinus montezumae complex: a coalescent approach to hybridization. Evolution 54: 1218–1233

- ↑ Whittemore, A. T., Schaal, B. A. (1991) Interspecific gene flow in sympatric oaks. PNAS88: 2540-2544

- ↑ Ito, Y., T. Ohi-Toma, J. Murata, and Nr. Tanaka (2013) Comprehensive phylogenetic analyses of the Ruppia maritima complex focusing on taxa from the Mediterranean. Journal of Plant Research 126(6):753-62.

- ↑ Soltis, D. E., P. S. Soltis, T. G. Collier, and M. L. Edgerton. 1991. Chloroplast DNA variation within and among genera of the Heuchera group: evidence for extensive chloroplast capture and the paraphyly of Heuchera and Mitella. American Journal of Botany 78: 1091–1112.