Related Research Articles

Korean shamanism, also known as musok or Mu-ism, is a religion from Korea. Scholars of religion classify it as a folk religion and sometimes regard it as one facet of a broader Korean vernacular religion distinct from Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism. There is no central authority in control of musok, with much diversity of belief and practice evident among practitioners.

Korean mythology is the group of myths told by historical and modern Koreans. There are two types: the written, literary mythology in traditional histories, mostly about the founding monarchs of various historical kingdoms, and the much larger and more diverse oral mythology, mostly narratives sung by shamans or priestesses (mansin) in rituals invoking the gods and which are still considered sacred today.

Stories and practices that are considered part of Korean folklore go back several thousand years. These tales derive from a variety of origins, including Shamanism, Confucianism, Buddhism, and more recently Christianity.

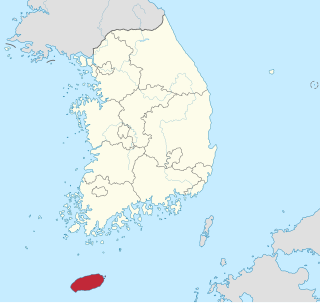

Jeju, often called Jejueo or Jejuan in English-language scholarship, is a Koreanic language originally from Jeju Island, South Korea. It is not mutually intelligible with mainland Korean dialects. While it was historically considered a divergent Jeju dialect of the Korean language, it is increasingly referred to as a separate language in its own right. It is declining in usage and was classified by UNESCO in 2010 as critically endangered, the highest level of language endangerment possible. Revitalization efforts are ongoing.

Gut are the rites performed by Korean shamans, involving offerings and sacrifices to gods, spirits and ancestors. They are characterised by rhythmic movements, songs, oracles and prayers. These rites are meant to create welfare, promoting commitment between the spirits and humankind. The major categories of rites are the naerim-gut, the dodang-gut and the ssitgim-gut.

Martina Deuchler is a Swiss academic and author. She was a professor of Korean studies at the SOAS University of London from 1991 to 2001.

Tamra, the Island is a 2009 South Korean television series starring Seo Woo, Im Joo-hwan and Pierre Deporte. It aired on MBC from August 8 to September 27, 2009 on Saturdays and Sundays at 19:55 for 20 episodes.

Warm and Cozy is a 2015 South Korean television series starring Kang So-ra and Yoo Yeon-seok. Written by the Hong sisters as a twist on the fable of The Ant and the Grasshopper, it aired on MBC from May 13 to July 2, 2015 on Wednesdays and Thursdays at 22:00 for 16 episodes.

The bon-puri are Korean shamanic narratives recited in the shamanic rituals of Jeju Island, to the south of the Korean Peninsula. Similar shamanic narratives are known in mainland Korea as well, but are only occasionally referred to as bon-puri.

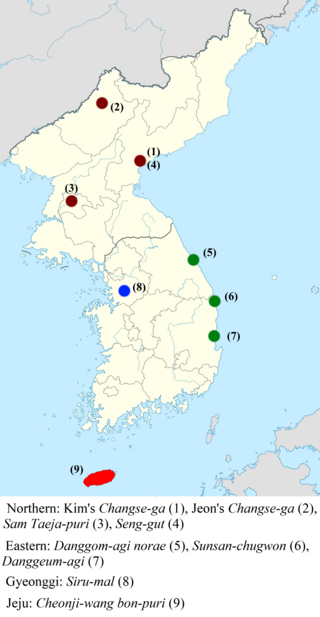

Korean creation narratives are Korean shamanic narratives which recount the mythological beginnings of the universe. They are grouped into two categories: the eight narratives of mainland Korea, which were transcribed by scholars between the 1920s and 1980s, and the Cheonji-wang bon-puri narrative of southern Jeju Island, which exists in multiple versions and continues to be sung in its ritual context today. The mainland narratives themselves are subdivided into four northern and three eastern varieties, along with one from west-central Korea.

The Seng-gut narrative is a Korean shamanic narrative traditionally recited in a large-scale gut ritual in Hamgyong Province, North Korea. It tells of the deeds of one or multiple deities referred to as "sages," beginning from the creation of the world. It combines many stories that appear independently in other regions of Korea into a single extended narrative. In the first story, the deity Seokga usurps the world from the creator, creates animals from deer meat, and destroys a superfluous sun and moon. In the second, the carpenter Gangbangdek builds a palace for the gods, loses a wager to a woman, and becomes the god of the household. In the third and fourth stories, a boy who does not talk until the age of ten becomes the founder of a new Buddhist temple and melts a baby into iron to forge a temple bell. In the fifth, the same priest destroys a rich man for having abused him. Finally, the priest makes his three sons the gods of fertility, ending the story. The narrative has a strong Buddhist influence.

Life replacement narratives or life extension narratives refer to three Korean shamanic narratives chanted during religious rituals, all from different regional traditions of mythology but with a similar core story: the Menggam bon-puri of the Jeju tradition, the Jangja-puri of the Jeolla tradition, and the Honswi-gut narrative of the South Hamgyong tradition. As oral literature, all three narratives exist in multiple versions.

The Song of Dorang-seonbi and Cheongjeong-gaksi is a Korean shamanic narrative recited in the Mangmuk-gut, the traditional funeral ceremony of South Hamgyong Province, North Korea. It is the most ritually important and most popular of the many mythological stories told in this ritual. The Mangmuk-gut is no longer performed in North Korea, but the ritual and the narrative are currently being passed down by a South Korean community descended from Hamgyong refugees.

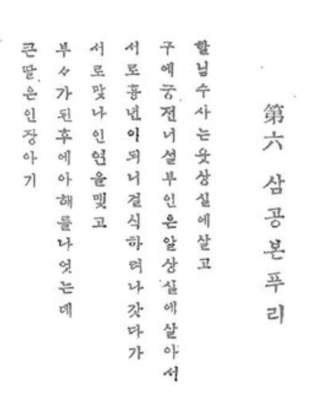

The Samgong bon-puri (Korean: 삼공본풀이) is a Korean shamanic narrative recited in southern Jeju Island, associated with the goddess Samgong. It is among the most important of the twelve general bon-puri, which are the narratives known by all Jeju shamans.

The mengdu, also called the three mengdu and the three mengdu of the sun and moon, are a set of three kinds of brass ritual devices—a pair of knives, a bell, and divination implements—which are the symbols of shamanic priesthood in the Korean shamanism of southern Jeju Island. Although similar ritual devices are found in mainland Korea, the religious reverence accorded to the mengdu is unique to Jeju.

The Semin-hwangje bon-puri is a Korean shamanic narrative formerly recited in southern Jeju Island during the funeral ceremonies. As it is no longer transmitted by the oral tradition, it is classified as one of the special bon-puri.

The Naewat-dang shamanic paintings are ten portraits of village patron gods formerly hung at the Naewat-dang shrine, one of the four state-recognized shamanic temples of Jeju Island, now in South Korea. The shrine was destroyed in the nineteenth century, and the works are currently preserved at Jeju National University as a government-designated Important Folklore Cultural Property. They may be the oldest Korean shamanic paintings currently known.

Gongsim is a legendary Korean princess of the Goryeo dynasty said to have been struck with sinbyeong, an illness which can only be cured by initiation into shamanism. According to the myth, she joined the shamanic priesthood at Namsan Mountain in Seoul, and introduced the shamanic religion to Korea or to parts of Korea.

Gawp is a cosmological concept in Jeju Island shamanism referring to the divide between heaven and earth, humans and non-humans, and the living and the dead.

The Durin-gut, also called the Michin-gut and the Chuneun-gut, is the healing ceremony for mental illnesses in the Korean shamanism of southern Jeju Island. While commonly held as late as the 1980s, it has now become very rare due to the introduction of modern psychiatry.

References

Citations

- 1 2 Kang J. 2015, pp. 154–156.

- ↑ "신뿌리"; <초공본풀이>에서 그러했기 때문이라는 답" Shin Y. (2017) , p. 228

- ↑ Kang S. 2012, p. 30.

- ↑ Kang J. 2015, p. 15.

- ↑ Seo D. 2001, pp. 262–264.

- ↑ Hyun Y. & Hyun S. 1996, pp. 40–47.

- ↑ Hyun Y. & Hyun S. 1996, pp. 47–49.

- ↑ Hyun Y. & Hyun S. 1996, pp. 49–53.

- ↑ Hyun Y. & Hyun S. 1996, pp. 53–59.

- ↑ Hyun Y. & Hyun S. 1996, pp. 59–65.

- ↑ "삼천천제석궁" Hyun Y. & Hyun S. (1996) , pp. 65–73

- ↑ Shin Y. 2017, p. 14.

- 1 2 Hyun Y. & Hyun S. 1996, pp. 73–79.

- ↑ Kang S. 2012, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Hyun Y. & Hyun S. 1996, pp. 79–81.

- ↑ Kang S. 2012, pp. 103–104.

Sources

- 홍태한 (Hong Tae-han) (2002). Han'guk seosa muga yeon'gu한국 서사무가 연구[Studies on Korean Shamanic Narratives]. Seoul: Minsogwon. ISBN 978-89-5638-053-7. Anthology of prior papers.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - —————————— (2016). Han'guk seosa muga-ui yuhyeong-byeol jonjae yangsang-gwa yeonhaeng wolli한국 서사무가의 유형별 존재양상과 연행원리[Forms per type and principles of performances in Korean shamanic narratives]. Seoul: Minsogwon. ISBN 978-89-285-0881-5. Anthology of prior papers.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - 현용준 (Hyun Yong-jun); 현승환 (Hyun Seung-hwan) (1996). Jeju-do muga제주도 무가[Shamanic hymns of Jeju Island]. Han'guk gojeon munhak jeonjip. Research Institute of Korean Studies, Korea University.

- 강소전 (Kang So-jeon) (2012). Jeju-do simbang-ui mengdu yeon'gu: Giwon, jeonseung, uirye-reul jungsim-euro제주도 심방의 멩두 연구—기원,전승,의례를 중심으로-[Study on the mengdu of Jeju shamans: Origins, transfer, ritual] (PhD). Cheju National University.

- 강정식 (Kang Jeong-sik) (2015). Jeju Gut Ihae-ui Giljabi제주굿 이해의 길잡이 [A Primer to Understanding the Jeju Gut]. Jeju-hak Chongseo. Minsogwon. ISBN 978-89-285-0815-0 . Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- Kim, Hae-Kyung Serena (2005). Sciamanesimo e Chiesa in Corea: per un processo di evangelizzazione inculturata (in Italian). Gregorian Biblical BookShop. ISBN 978-88-7839-025-6.

- Kim, Tae-kon (1998). Korean Shamanism—Muism. Jimoondang Publishing Company. ISBN 978-89-88095-09-6.

- 김, 태곤 (1996). 한국의 무속. Daewonsa. ISBN 978-89-5653-907-2.

- Lee, Chi-ran (2010s). "The Emergence of National Religions in Korea" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2014.

- 서대석 (Seo Daeseok) (2001). Han'guk sinhwa-ui yeon'gu한국 신화의 연구 [Studies on Korean Mythology]. Seoul: Jibmundang. ISBN 978-89-303-0820-5 . Retrieved June 23, 2020. Anthology of Seo's papers from the 1980s and 1990s.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - 서대석 (Seo Daeseok); 박경신 (Park Gyeong-sin) (1996). Seosa muga il서사무가 1[Narrative shaman hymns, Volume I]. Han'guk gojeon munhak jeonjip. Research Institute of Korean Studies, Korea University.

- 신연우 (Shin Yeon-woo) (2017). Jeju-do seosa muga Chogong bon-puri-ui sinhwa-seong-gwa munhak-seong제주도 서사무가 <초공본풀이>의 신화성과 문학성[The Mythological and Literary Nature of the Jeju Shamanic Narrative Chogong bon-puri]. Seoul: Minsogwon. ISBN 978-89-285-1036-8.

- Yunesŭk'o Han'guk Wiwŏnhoe (1985). "Korea Journal". Korean National Commission for UNESCO.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Keith Howard (Hrsg.): Korean Shamanism. Revival, survivals and change. The Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch, Seoul Press, Seoul 1998.

- Dong Kyu Kim: Looping effects between images and realities: understanding the plurality of Korean shamanism. The University of British Columbia, 2012.

- Laurel Kendall: Shamans, housewives and other restless spirits. Woman in Korean ritual life (= Studies of the East Asien Institute.). University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1985.

- Kwang-Ok Kim: Rituals of resistance. The manipulation of shamanism in contemporary Korea. In: Charles F. Keyes; Laurel Kendall; Helen Hardacre (Hrsg.): Asian visions of authority. Religion and the modern states of East and Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1994, S. 195–219.

- Hogarth, Hyun-key Kim (1998). Kut: Happiness Through Reciprocity. Bibliotheca shamanistica. Vol. 7. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 978-963-05-7545-4. ISSN 1218-988X.

- Daniel Kister: Korean shamanist ritual. Symbols and dramas of transformation. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1997.

- Dirk Schlottmann: Cyber Shamanism in South Korea. Online Publication: Institut of Cyber Society. Kyung Hee Cyber University, Seoul 2014.

- Dirk Schlottmann Spirit Possession in Korean Shaman rituals of the Hwanghaedo-Tradition.In: Journal for the Study of Religious Experiences. Vol.4 No.2. The Religious Experience Research Centre (RERC) at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David, Wales 2018.

- Dirk Schlottmann Dealing with Uncertainty: “Hell Joseon” and the Korean Shaman rituals for happiness and against misfortune. In: Shaman – Journal of the International Society for Academic Research on Shamanism. Vol. 27. no 1 & 2, p. 65–95. Budapest: Molnar & Kelemen Oriental Publishers 2019.