Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to many other branches of mathematics, such as binary arithmetic and statistics. Leibniz has been called the "last universal genius" due to his vast expertise across fields, which became a rarity after his lifetime with the coming of the Industrial Revolution and the spread of specialized labor. He is a prominent figure in both the history of philosophy and the history of mathematics. He wrote works on philosophy, theology, ethics, politics, law, history, philology, games, music, and other studies. Leibniz also made major contributions to physics and technology, and anticipated notions that surfaced much later in probability theory, biology, medicine, geology, psychology, linguistics and computer science.

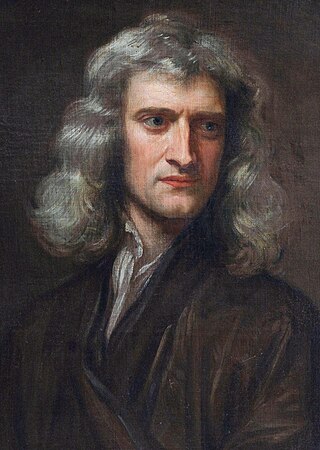

Sir Isaac Newton was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author who was described in his time as a natural philosopher. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment that followed. Newton's book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, first published in 1687, achieved the first great unification in physics and established classical mechanics. Newton also made seminal contributions to optics, and shares credit with German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz for formulating infinitesimal calculus, though he developed calculus years before Leibniz. He contributed to and refined the scientific method, and his work is considered the most influential in bringing forth modern science.

Space is a three-dimensional continuum containing positions and directions. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions. Modern physicists usually consider it, with time, to be part of a boundless four-dimensional continuum known as spacetime. The concept of space is considered to be of fundamental importance to an understanding of the physical universe. However, disagreement continues between philosophers over whether it is itself an entity, a relationship between entities, or part of a conceptual framework.

Time is the continuous progression of our changing existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to compare the duration of events, and to quantify rates of change of quantities in material reality or in the conscious experience. Time is often referred to as a fourth dimension, along with three spatial dimensions. Scientists have theorized a beginning of time in our universe and an end. A cyclic model describes a cyclical nature, whereas the philosophy of eternalism views the subject from a different angle.

The teleological argument also known as physico-theological argument, argument from design, or intelligent design argument, is a rational argument for the existence of God or, more generally, that complex functionality in the natural world, which looks designed, is evidence of an intelligent creator. The earliest recorded versions of this argument are associated with Socrates in ancient Greece, although it has been argued that he was taking up an older argument. Later, Plato and Aristotle developed complex approaches to the proposal that the cosmos has an intelligent cause, but it was the Stoics during the Roman era who, under their influence, "developed the battery of creationist arguments broadly known under the label 'The Argument from Design'".

The Age of Enlightenment was an intellectual and philosophical movement that occurred in Europe in the 17th and the 18th centuries. The Enlightenment featured a range of social ideas centered on the value of knowledge learned by way of rationalism and of empiricism and political ideals such as natural law, liberty, and progress, toleration and fraternity, constitutional government, and the formal separation of church and state.

Determinism is the philosophical view that all events in the universe, including human decisions and actions, are causally inevitable. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and considerations. Like eternalism, determinism focuses on particular events rather than the future as a concept. Determinism is often contrasted with free will, although some philosophers claim that the two are compatible. A more extreme antonym of determinism is indeterminism, or the view that events are not deterministically caused but rather occur due to random chance.

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or “the position that reason has precedence over other ways of acquiring knowledge”, often in contrast to other possible sources of knowledge such as faith, tradition, or sensory experience. More formally, rationalism is defined as a methodology or a theory "in which the criterion of truth is not sensory but intellectual and deductive".

In philosophy, absolute theory usually refers to a theory based on concepts that exist independently of other concepts and objects. The absolute point of view was advocated in physics by Isaac Newton. It is one of the traditional views of space along with relational theory and the Kantian theory.

Early modern philosophy The early modern era of philosophy was a progressive movement of Western thought, exploring through theories and discourse such topics as mind and matter, is a period in the history of philosophy that overlaps with the beginning of the period known as modern philosophy. It succeeded the medieval era of philosophy. Early modern philosophy is usually thought to have occurred between the 16th and 18th centuries, though some philosophers and historians may put this period slightly earlier. During this time, influential philosophers included Descartes, Locke, Hume, and Kant, all of whom contributed to the current understanding of philosophy.

Absolute space and time is a concept in physics and philosophy about the properties of the universe. In physics, absolute space and time may be a preferred frame.

Edward Ishmael Dolnick is an American writer, formerly a science writer at the Boston Globe. He has been published in Atlantic Monthly, The New York Times Magazine, and The Washington Post, among other publications.

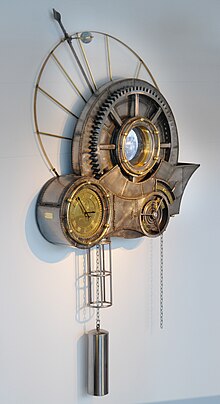

The watchmaker analogy or watchmaker argument is a teleological argument, an argument for the existence of God. In broad terms, the watchmaker analogy states that just as it is readily observed that a watch did not come to be accidentally or on its own but rather through the intentional handiwork of a skilled watchmaker, it is also readily observed that nature did not come to be accidentally or on its own but through the intentional handiwork of an intelligent designer. The watchmaker analogy originated in natural theology and is often used to argue for the pseudoscientific concept of intelligent design. The analogy states that a design implies a designer, by an intelligent designer, i.e. a creator deity. The watchmaker analogy was given by William Paley in his 1802 book Natural Theology or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity. The original analogy played a prominent role in natural theology and the "argument from design," where it was used to support arguments for the existence of God of the universe, in both Christianity and Deism. Prior to Paley, however, Sir Isaac Newton, René Descartes, and others from the time of the Scientific Revolution had each believed "that the physical laws he [each] had uncovered revealed the mechanical perfection of the workings of the universe to be akin to a watch, wherein the watchmaker is God."

De sphaera mundi is a medieval introduction to the basic elements of astronomy written by Johannes de Sacrobosco c. 1230. Based heavily on Ptolemy's Almagest, and drawing additional ideas from Islamic astronomy, it was one of the most influential works of pre-Copernican astronomy in Europe.

Isaac Newton was considered an insightful and erudite theologian by his Protestant contemporaries. He wrote many works that would now be classified as occult studies, and he wrote religious tracts that dealt with the literal interpretation of the Bible. He kept his heretical beliefs private.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to metaphysics:

Philosophical theism is the belief that the Supreme Being exists independent of the teaching or revelation of any particular religion. It represents belief in God entirely without doctrine, except for that which can be discerned by reason and the contemplation of natural laws. Some philosophical theists are persuaded of God's existence by philosophical arguments, while others consider themselves to have a religious faith that need not be, or could not be, supported by rational argument.

Deism, the religious attitude typical of the Enlightenment, especially in France and England, holds that the only way the existence of God can be proven is to combine the application of reason with observation of the world. A Deist is defined as "One who believes in the existence of a God or Supreme Being but denies revealed religion, basing his belief on the light of nature and reason." Deism was often synonymous with so-called natural religion because its principles are drawn from nature and human reasoning. In contrast to Deism there are many cultural religions or revealed religions, such as Judaism, Trinitarian Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and others, which believe in supernatural intervention of God in the world; while Deism denies any supernatural intervention and emphasizes that the world is operated by natural laws of the Supreme Being.

Mechanism is the belief that natural wholes are similar to complicated machines or artifacts, composed of parts lacking any intrinsic relationship to each other.