Anti-competitive practices are business or government practices that prevent or reduce competition in a market. Antitrust laws ensure businesses do not engage in competitive practices that harm other, usually smaller, businesses or consumers. These laws are formed to promote healthy competition within a free market by limiting the abuse of monopoly power. Competition allows companies to compete in order for products and services to improve; promote innovation; and provide more choices for consumers. In order to obtain greater profits, some large enterprises take advantage of market power to hinder survival of new entrants. Anti-competitive behavior can undermine the efficiency and fairness of the market, leaving consumers with little choice to obtain a reasonable quality of service.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) is the chief competition regulator of the Government of Australia, located within the Department of the Treasury. It was established in 1995 with the amalgamation of the Australian Trade Practices Commission and the Prices Surveillance Authority to administer the Trade Practices Act 1974, which was renamed the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 on 1 January 2011. The ACCC's mandate is to protect consumer rights and business rights and obligations, to perform industry regulation and price monitoring, and to prevent illegal anti-competitive behaviour.

Predatory pricing is a commercial pricing strategy which involves the use of large scale undercutting to eliminate competition. This is where an industry dominant firm with sizable market power will deliberately reduce the prices of a product or service to loss-making levels to attract all consumers and create a monopoly. For a period of time, the prices are set unrealistically low to ensure competitors are unable to effectively compete with the dominant firm without making substantial loss. The aim is to force existing or potential competitors within the industry to abandon the market so that the dominant firm may establish a stronger market position and create further barriers to entry. Once competition has been driven from the market, consumers are forced into a monopolistic market where the dominant firm can safely increase prices to recoup its losses.

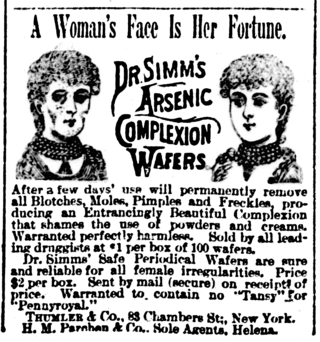

False advertising is the act of publishing, transmitting, or otherwise publicly circulating an advertisement containing a false claim, or statement, made intentionally to promote the sale of property, goods, or services. A false advertisement can be classified as deceptive if the advertiser deliberately misleads the consumer, rather than making an unintentional mistake. A number of governments use regulations to limit false advertising.

A standard form contract is a contract between two parties, where the terms and conditions of the contract are set by one of the parties, and the other party has little or no ability to negotiate more favorable terms and is thus placed in a "take it or leave it" position.

The National Electricity Market (NEM) is an arrangement in Australia's electricity sector for the connection of the electricity transmission grids of the eastern and southern Australia states and territories to create a cross-state wholesale electricity market. The Australian Energy Market Commission develops and maintains the Australian National Electricity Rules (NER), which have the force of law in the states and territories participating in NEM. The Rules are enforced by the Australian Energy Regulator. The day-to-day management of NEM is performed by the Australian Energy Market Operator.

In Economics and Law, exclusive dealing arises when a supplier entails the buyer by placing limitations on the rights of the buyer to choose what, who and where they deal. This is against the law in most countries which include the USA, Australia and Europe when it has a significant impact of substantially lessening the competition in an industry. When the sales outlets are owned by the supplier, exclusive dealing is because of vertical integration, where the outlets are independent exclusive dealing is illegal due to the Restrictive Trade Practices Act, however, if it is registered and approved it is allowed. While primarily those agreements imposed by sellers are concerned with the comprehensive literature on exclusive dealing, some exclusive dealing arrangements are imposed by buyers instead of sellers.

In common law jurisdictions, an implied warranty is a contract law term for certain assurances that are presumed to be made in the sale of products or real property, due to the circumstances of the sale. These assurances are characterized as warranties regardless of whether the seller has expressly promised them orally or in writing. They include an implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose, an implied warranty of merchantability for products, implied warranty of workmanlike quality for services, and an implied warranty of habitability for a home.

Misleading or deceptive conduct is a doctrine of Australian law.

In United States antitrust law, monopolization is illegal monopoly behavior. The main categories of prohibited behavior include exclusive dealing, price discrimination, refusing to supply an essential facility, product tying and predatory pricing. Monopolization is a federal crime under Section 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. It has a specific legal meaning, which is parallel to the "abuse" of a dominant position in EU competition law, under TFEU article 102. It is also illegal in Australia under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (CCA). Section 2 of the Sherman Act states that any person "who shall monopolize. .. any part of the trade or commerce among the several states, or with foreign nations shall be deemed guilty of a felony." Section 2 also forbids "attempts to monopolize" and "conspiracies to monopolize". Generally this means that corporations may not act in ways that have been identified as contrary to precedent cases.

Though in general, each business may decide with whom they wish to transact, there are some situations when a refusal to deal may be considered an unlawful anti-competitive practice, if it prevents or reduces competition in a market. The unlawful behaviour may involve two or more companies refusing to use, buy from or otherwise deal with a person or business, such as a competitor, for the purpose of inflicting some economic loss on the target or otherwise force them out of the market. A refusal to deal is forbidden in some countries which have restricted market economies, though the actual acts or situations which may constitute such unacceptable behaviour may vary significantly between jurisdictions.

This is a partial list of notable price fixing and bid rigging cases.

The Commerce Commission is a New Zealand government agency with responsibility for enforcing legislation that relates to competition in the country's markets, fair trading and consumer credit contracts, and regulatory responsibility for areas such as electricity and gas, telecommunications, dairy products and airports. It is an independent Crown entity established under the Commerce Act 1986. Although responsible to the Minister of Commerce and Consumer Affairs and the Minister of Broadcasting, Communications and Digital Media, the Commission is run independently from the government, and is intended to be an impartial promotor and enforcer of the law.

The history of competition law refers to attempts by governments to regulate competitive markets for goods and services, leading up to the modern competition or antitrust laws around the world today. The earliest records traces back to the efforts of Roman legislators to control price fluctuations and unfair trade practices. Throughout the Middle Ages in Europe, kings and queens repeatedly cracked down on monopolies, including those created through state legislation. The English common law doctrine of restraint of trade became the precursor to modern competition law. This grew out of the codifications of United States antitrust statutes, which in turn had considerable influence on the development of European Community competition laws after the Second World War. Increasingly, the focus has moved to international competition enforcement in a globalised economy.

Consumer protection is the practice of safeguarding buyers of goods and services, and the public, against unfair practices in the marketplace. Consumer protection measures are often established by law. Such laws are intended to prevent businesses from engaging in fraud or specified unfair practices to gain an advantage over competitors or to mislead consumers. They may also provide additional protection for the general public which may be impacted by a product even when they are not the direct purchaser or consumer of that product. For example, government regulations may require businesses to disclose detailed information about their products—particularly in areas where public health or safety is an issue, such as with food or automobiles.

Telstra Corporation Limited v. The Commonwealth was an important case decided in the High Court of Australia on 6 March 2008.

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Baxter Healthcare Pty Ltd, (Baxter) was a decision of the High Court of Australia, which ruled on 29 August 2007 that Baxter Healthcare Proprietary Limited, a tenderer for various government contracts, was bound by the Trade Practices Act 1974 in its trade and commerce in tendering for government contracts. More generally, the case concerned the principles of derivative governmental immunity: whether the immunity of a government from a statute extends to third parties that conduct business with the government.

The Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010, is uniform legislation for consumer protection, applying as a law of the Commonwealth of Australia and is incorporated into the law of each of Australia's states and territories. The law commenced on 1 January 2011, replacing 20 different consumer laws across the Commonwealth and the states and territories, although certain other Acts continue to be in force.

The Competition Act, 2002 was enacted by the Parliament of India and governs Indian competition law. It replaced the archaic The Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act, 1969. Under this legislation, the Competition Commission of India was established to prevent the activities that have an adverse effect on competition in India. This act extends to whole of India.

ACCC v Cabcharge Australia Ltd is a 2010 decision of the Federal Court of Australia brought by the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (ACCC) against Cabcharge. In June 2009, the ACCC began proceedings in the Federal Court against Cabcharge alleging that it had breached section 46 of the Commonwealth Trade Practices Act (TPA) by misusing its market power and entering into an agreement to substantially lessen competition. The action alleged predatory pricing by Cabcharge and centred on Cabcharge's conduct in refusing to deal with competing suppliers to allow Cabcharge payments to be processed through EFTPOS terminals provided by rival companies and supplying taxi meters and fare updates at below actual cost or at no cost.