Related Research Articles

A concerto is, from the late Baroque era, mostly understood as an instrumental composition, written for one or more soloists accompanied by an orchestra or other ensemble. The typical three-movement structure, a slow movement preceded and followed by fast movements, became a standard from the early 18th century.

Alban Berg's Violin Concerto was written in 1935. It is probably Berg's best-known and most frequently performed instrumental piece, in which the composer sought to reconcile diatonicism and dodecaphony. The work was commissioned by Louis Krasner, and dedicated by Berg to "the memory of an angel", Manon Gropius. It was the last work that Berg completed. Krasner performed the solo part in the premiere at the Palau de la Música Catalana, Barcelona, on 19 April 1936, after the composer's death.

The concerto grosso is a form of baroque music in which the musical material is passed between a small group of soloists and full orchestra. This is in contrast to the solo concerto which features a single solo instrument with the melody line, accompanied by the orchestra.

Trevor David Pinnock is a British harpsichordist and conductor.

A harpsichord concerto is a piece of music for an orchestra with the harpsichord in a solo role. Sometimes these works are played on the modern piano. For a period in the late 18th century, Joseph Haydn and Thomas Arne wrote concertos that could be played interchangeably on harpsichord, fortepiano, and pipe organ.

The keyboard concertos, BWV 1052–1065, are concertos for harpsichord, strings and continuo by Johann Sebastian Bach. There are seven complete concertos for a single harpsichord, three concertos for two harpsichords, two concertos for three harpsichords, and one concerto for four harpsichords. Two other concertos include solo harpsichord parts: the concerto BWV 1044, which has solo parts for harpsichord, violin and flute, and Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D major, with the same scoring. In addition, there is a nine-bar concerto fragment for harpsichord which adds an oboe to the strings and continuo.

The Symphony No. 9 by Alfred Schnittke was written two years before his death in 1998. As a result of paralysis following a series of strokes, the manuscript was barely readable, and a performing edition was made by Gennady Rozhdestvensky. Schnittke was dissatisfied with Rozhdestvensky's edition, and following his death his widow Irina Schnittke sought to have a reconstruction made that was more faithful to the manuscript. Nikolai Korndorf was first engaged to perform the task, and following his early death the manuscript was passed to Alexander Raskatov. Raskatov not only reconstructed Schnittke's Ninth but also wrote his own composition: Nunc dimittis – In memoriam Alfred Schnittke, which was performed after the symphony in the premiere recording conducted by Dennis Russell Davies.

A violin sonata is a musical composition for violin, often accompanied by a keyboard instrument and in earlier periods with a bass instrument doubling the keyboard bass line. The violin sonata developed from a simple baroque form with no fixed format to a standardised and complex classical form. Since the romantic age some composers have pushed the boundaries of both the classical format as well as the use of the instruments.

The Twelve Grand Concertos, Op. 6, HWV 319–330, by George Frideric Handel are concerti grossi for a concertino trio of two violins and cello and a ripieno four-part string orchestra with harpsichord continuo. First published by subscription in London by John Walsh in 1739, they became in a second edition two years later Handel's Opus 6. Taking the older concerto da chiesa and concerto da camera of Arcangelo Corelli as models, rather than the later three-movement Venetian concerto of Antonio Vivaldi favoured by Johann Sebastian Bach, they were written to be played during performances of Handel's oratorios and odes. Despite the conventional model, Handel incorporated in the movements the full range of his compositional styles, including trio sonatas, operatic arias, French overtures, Italian sinfonias, airs, fugues, themes and variations and a variety of dances. The concertos were largely composed of new material: they are amongst the finest examples in the genre of baroque concerto grosso.

The Musette, or rather chaconne, in this Concerto, was always in favour with the composer himself, as well as the public; for I well remember that HANDEL frequently introduced it between the parts of his Oratorios, both before and after publication. Indeed no instrumental composition that I have ever heard during the long favour of this, seemed to me more grateful and pleasing, particularly, in subject.

The Third Symphony by Alfred Schnittke was his fourth composition in the symphonic form, completed in 1981.

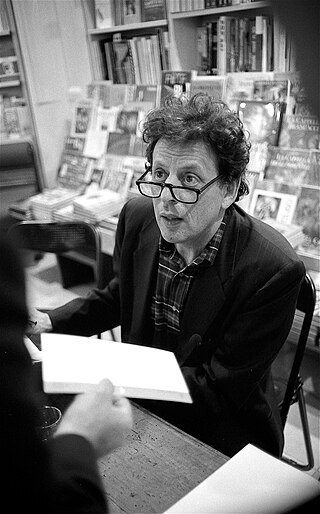

The Concerto for Harpsichord and Orchestra was completed by Philip Glass in spring of 2002. It was commissioned for the Northwest Chamber Orchestra by Charles and Diana Carey and published by Dunvagen Music. Glass wrote the concerto with the Baroque tradition in mind; however, in order to approach the work in a modern idiom, he calls for a contemporary chamber orchestra to accompany the harpsichord. The concerto was premiered in September 2002 in Seattle, with David Schrader as soloist performing with the Northwest Chamber Orchestra. It is approximately 20 minutes in length. The concerto was included in Glass' Concerto Project, a collection in four volumes.

The Concerto Grosso No. 1 was the first of six concerti grossi by Soviet composer Alfred Schnittke. It was written in 1976–1977 at the request of Gidon Kremer and Tatiana Grindenko who were also the violin soloists at its premiere on 21 March 1977 in Leningrad together with Yuri Smirnov on keyboard instruments and the Leningrad Chamber Orchestra under Eri Klas. It is one of the best-known of Schnittke's polystylistic compositions and marked his break-through in the West.

Johann Sebastian Bach wrote his fifth Brandenburg Concerto, BWV 1050.2, for harpsichord, flute and violin as soloists, and an orchestral accompaniment consisting of strings and continuo. An early version of the concerto, BWV 1050.1, originated in the late 1710s. On 24 March 1721 Bach dedicated the final form of the concerto to Margrave Christian Ludwig of Brandenburg.

The Harpsichord Concerto in A major, BWV 1055, is a concerto for harpsichord and string orchestra by Johann Sebastian Bach. It is the fourth keyboard concerto in Bach's autograph score of c. 1738.

The Harpsichord Concerto in E major, BWV 1053, is a concerto for harpsichord and string orchestra by Johann Sebastian Bach. It is the second of Bach's keyboard concerto composed in 1738, scored for keyboard and baroque string orchestra. The movements were reworkings of parts of two of Bach's church cantatas composed in 1726: the solo obbligato organ played the sinfonias for the two fast movements; and the remaining alto aria provided the slow movement.

The Harpsichord Concerto in D minor, BWV 1052, is a concerto for harpsichord and Baroque string orchestra by Johann Sebastian Bach. In three movements, marked Allegro, Adagio and Allegro, it is the first of Bach's harpsichord concertos, BWV 1052–1065.

The Concerto for Viola and Orchestra is a viola concerto by Soviet and German composer Alfred Schnittke. It was written in the summer of 1985. Its dedicatee is viola player Yuri Bashmet, who gave the work its world premiere with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra conducted by Lukas Vis at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam on 9 January 1986.

The Concerto no. 4 for Violin and Orchestra is a violin concerto by Soviet and German composer Alfred Schnittke. It was commissioned by the 34th Berlin Festival and written in 1984. Its first performance was given in Berlin on 11 September 1984 with dedicatee Gidon Kremer as soloist and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Christoph von Dohnányi.

Symphony No. 6 by Russian composer Alfred Schnittke was composed in 1992. It was commissioned by cellist and conductor Mstislav Rostropovich and the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington, who together gave its first performance in Moscow on 25 September 1993.

References

- ↑ Lindemann Malone, Andrew. Concerto Grosso No. 3, for 2... at AllMusic

- ↑ Simeone, Nigel (2015). Liner notes from Decca 478 8355. Decca Music Group Limited.

- 1 2 Schnittke, Alfred (1991). Liner notes in BIS-CD-537 (PDF). Åkersberga: BIS Records AB. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ↑ Schmelz, Peter J. (2019). Alfred Schnittke's Concerto Grosso No. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 124. ISBN 9780190653712 . Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sullivan, Tim (2010). "Structural Layers in Alfred Schnittke's Concerto Grosso No. 3". Perspectives of New Music . 48 (2): 21–46. ISSN 0031-6016. JSTOR 23076965.