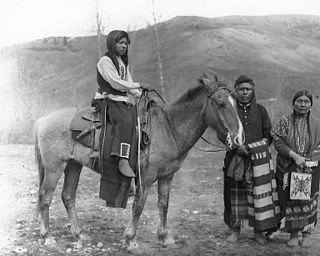

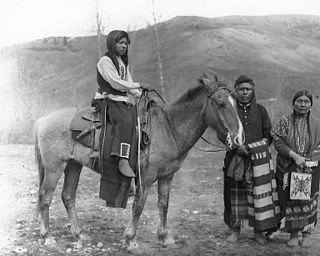

The Nez Perce are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who still live on a fraction of the lands on the southeastern Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest. This region has been occupied for at least 11,500 years.

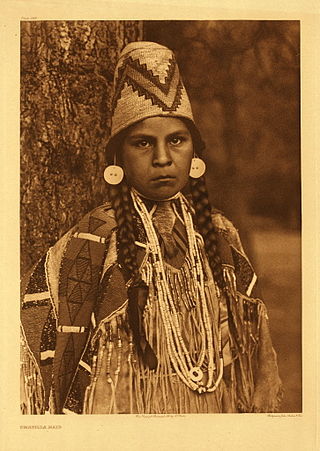

Walla Walla, Walawalałáma, sometimes Walúulapam, are a Sahaptin Indigenous people of the Northwest Plateau. The duplication in their name expresses the diminutive form. The name Walla Walla is translated several ways but most often as "many waters".

The Cayuse are a Native American tribe in what is now the state of Oregon in the United States. The Cayuse tribe shares a reservation and government in northeastern Oregon with the Umatilla and the Walla Walla tribes as part of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. The reservation is located near Pendleton, Oregon, at the base of the Blue Mountains.

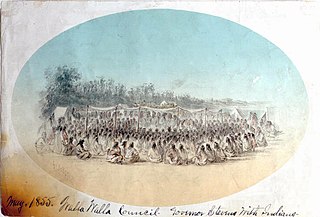

The Palouse are a Sahaptin tribe recognized in the Treaty of 1855 with the United States along with the Yakama. It was negotiated at the 1855 Walla Walla Council. A variant spelling is Palus. Today they are enrolled in the federally recognized Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation and some are also represented by the Colville Confederated Tribes, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation and Nez Perce Tribe.

The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation is the federally recognized tribe that controls the Colville Indian Reservation, which is located in northeastern Washington, United States. It is the government for its people.

The Umatilla are a Sahaptin-speaking Native American tribe who traditionally inhabited the Columbia Plateau region of the northwestern United States, along the Umatilla and Columbia rivers.

The Tamástslikt Cultural Institute is a museum and research institute located on the Umatilla Indian Reservation near Pendleton in eastern Oregon. It is the only Native American museum along the Oregon Trail. The institute is dedicated to the culture of the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla tribes of Native Americans. The main permanent exhibition of the museum provides a history of the culture of three tribes, and of the reservation itself. The museum also has a second hall for temporary exhibitions of specific types of Native American art, craftwork, history, and folklore related to the tribes.

The Umatilla Indian Reservation is an Indian reservation in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. It was created by The Treaty of 9 June 1855 between the United States and members of the Walla, Cayuse, and Umatilla tribes. It lies in northeastern Oregon, east of Pendleton. The reservation is mostly in Umatilla County, with a very small part extending south into Union County. It is managed by the three Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation.

The Whitman massacre was the killing of American missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, along with eleven others, on November 29, 1847. They were killed by a small group of Cayuse men who suspected that Whitman had poisoned the 200 Cayuse in his medical care during an outbreak of measles that included the Whitman household. The killings occurred at the Whitman Mission at the junction of the Walla Walla River and Mill Creek in what is now southeastern Washington near Walla Walla. The massacre became a decisive episode in the U.S. settlement of the Pacific Northwest, causing the United States Congress to take action declaring the territorial status of the Oregon Country. The Oregon Territory was established on August 14, 1848, to protect the white settlers.

Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Plateau, also referred to by the phrase Indigenous peoples of the Plateau, and historically called the Plateau Indians are Indigenous peoples of the Interior of British Columbia, Canada, and the non-coastal regions of the Northwestern United States.

Sahaptin, also called Ichishkiin, is one of the two-language Sahaptian branch of the Plateau Penutian family spoken in a section of the northwestern plateau along the Columbia River and its tributaries in southern Washington, northern Oregon, and southwestern Idaho, in the United States; the other language is Nez Perce (Niimi'ipuutímt).

The Wasco-Wishram are two closely related Chinook Indian tribes from the Columbia River in Oregon. Today the tribes are part of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs living in the Warm Springs Indian Reservation in Oregon and Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation living in the Yakama Indian Reservation in Washington.

The Umatilla River is an 89-mile (143 km) tributary of the Columbia River in northern Umatilla County, Oregon, United States. Draining a basin of 2,450 square miles (6,300 km2), it enters the Columbia near the city of Umatilla in the northeastern part of the state. In downstream order, beginning at the headwaters, major tributaries of the Umatilla River are the North Fork Umatilla River and the South Fork Umatilla River, then Meacham, McKay, Birch, and Butter creeks.

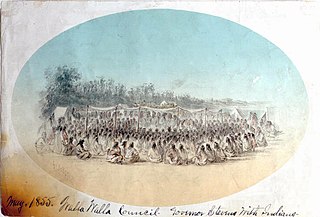

The Walla Walla Council (1855) was a meeting in the Pacific Northwest between the United States and sovereign tribal nations of the Cayuse, Nez Perce, Umatilla, Walla Walla, and Yakama. The council occurred on May 29 – June 11; the treaties signed at this council on June 9 were ratified by the U.S. Senate four years later in 1859.

Wildhorse Resort & Casino is a casino owned and operated since 1994 by the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation in the U.S. state of Oregon. It is located 5 mi (8 km) east of Pendleton, on the Umatilla Indian Reservation, near Interstate 84.

Umatilla is a variety of Southern Sahaptin, part of the Sahaptian subfamily of the Plateau Penutian group. It was spoken during late aboriginal times along the Columbia River and is therefore also called Columbia River Sahaptin. It is currently spoken as a first language by a few dozen elders and some adults in the Umatilla Reservation in Oregon. Some sources say that Umatilla is derived from imatilám-hlama: hlama means 'those living at' or 'people of' and there is an ongoing debate about the meaning of imatilám, but it is said to be an island in the Columbia River. B. Rigsby and N. Rude mention the village of ímatalam that was situated at the mouth of the Umatilla River and where the language was spoken.

The Oregon Superintendent of Indian Affairs was an official position of the U.S. state of Oregon, and previously of the Oregon Territory, that existed from 1848 to 1873.

The history of Walla Walla, Washington begins with the settling of Oregon Country, Fort Nez Percés, the Whitman Mission and Walla Walla County, Washington.

Charles F. Sams III is an American conservationist who is the 19th and current director of the National Park Service since 2021. A member of the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, Sams is the first Native American to serve as head of the NPS.

Roberta "Bobbie" Conner, also known as Sísaawipam, is a tribal historian, activist, and indigenous leader who traces her ancestry to the Umatilla, Cayuse, and Nez Perce tribes. Conner is known for her work as the Director of the Tamástslikt Cultural Institute in Pendleton, Oregon, which seeks to protect, preserve, and promote the culture of the Umatilla, Cayuse, and Walla Walla peoples. In her role at the Tamástslikt Cultural Institute Conner has worked to educate the public on and preserve Indigenous culture through the "We Are," "We Were," and "We Will Be" series of exhibits, and has mentored young scholars interested in tribal cultural preservation. Conner has also sought to educate the public and fight for Native American rights in her personal life as an activist, with a special emphasis on the impact of the division into Tribal Nations and segregation into boarding schools on indigenous cultures, tribal land rights, sustainability, and the repatriation of human remains and funerary objects to Native American lands.