Related Research Articles

Year 962 (CMLXII) was a common year starting on Wednesday of the Julian calendar.

Bobbio is a small town and comune in the province of Piacenza in Emilia-Romagna, northern Italy. It is located in the Trebbia River valley southwest of the town Piacenza. There is also an abbey and a diocese of the same name. Bobbio is the administrative center of the Unione Montana Valli Trebbia e Luretta. It is a member of the I Borghi più belli d'Italia association.

Lambert was the King of Italy from 891, Holy Roman Emperor, co-ruling with his father from 892, and Duke of Spoleto and Camerino from his father's death in 894. He was the son of Guy III of Spoleto and Ageltrude, born in San Rufino. He was the last ruler to issue a capitulary in the Carolingian tradition.

Boso was a Frankish nobleman of the Bosonid family who was related to the Carolingian dynasty and who rose to become King of Lower Burgundy and Provence.

Adalbert II, called the Rich, son of Adalbert I, Margrave of Tuscany and Rothild of Spoleto. He was a grandson of Boniface II, and was concerned with the troubles of Lombardy, at a time when so many princes were contending for the wreckage of the Carolingian Empire. Before his father died in 884 or 886, he is accredited the title of "count". He inherited from his father the titles of Count and Duke of Lucca and Margrave of Tuscany.

Hugh, called the Great, was the Margrave of Tuscany from 969 until his death in 1001, and the Duke of Spoleto and Margrave of Camerino from 989 to 996. He was known for his restoration of the state apparatus in Tuscany after decades of neglect from various Margraves, whose main interests lay elsewhere. Hugh was also noted for his support of the new Ottonian dynasty, and has been praised for his justice by the contemporary theologian Peter Damian in his De principis officio. Hugh's rule has also been remembered for its close cooperation with the Papal States in the resolution of territorial disputes and his generosity in gifting marchesal (public) lands for the foundation of monasteries of the Catholic Church.

The March of Ivrea was a large frontier county (march) in the northwest of the medieval Italian kingdom from the late 9th to the early 11th century. Its capital was Ivrea in present-day Piedmont, and it was held by a Burgundian family of margraves called the Anscarids. The march was the primary frontier between Italy and Upper Burgundy and served as a defense against any interference from that state.

The House of Ardenne–Verdun was a branch of the House of Ardenne, one of the first documented medieval European noble families, centered on Verdun. The family dominated in the Duchy of Lotharingia (Lorraine) in the 10th and 11th centuries. All members descended from Cunigunda of France, a granddaughter of the West Frankish king Louis the Stammerer. She married twice but all or most of her children were children of her first husband, Count Palatine Wigeric of Lotharingia. The other main branches of the House of Ardennes were the House of Ardenne–Luxembourg, and the House of Ardenne–Bar.

The Supponids were a Frankish noble family of prominence in the Carolingian regnum Italicum in the ninth century. They were descended from Suppo I, who appeared for the first time in 817 as a strong ally of the Emperor Louis the Pious. He and his descendants were on and off dukes of Spoleto, commonly in opposition to the Guideschi clan, another Frankish family powerful in central Italy.

The House of Obertenghi were a prominent Italian noble family of Frankish origin descended from Viscount Adalbert III, first Margrave of Milan.

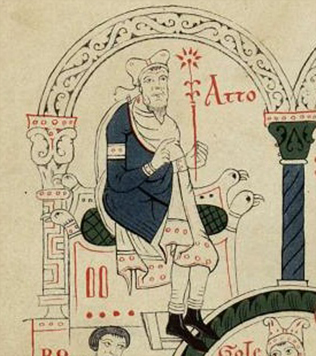

Adalbert Atto was the first Count of Canossa and founder of that noble house which eventually was to play a determinant role in the political settling of Regnum Italicum and the Investiture Controversy in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

Albert Azzo I was an Italian nobleman. He was a member of the Obertenghi family. From 1014 onward, he was margrave of Milan and count of Luni, Genoa and Tortona.

The March of Tuscany was a march of the Kingdom of Italy and the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages. Located in northwestern central Italy, it bordered the Papal States to the south, the Ligurian Sea to the west and Lombardy to the north. It comprised a collection of counties, largely in the valley of the Arno River, originally centered on Lucca.

The Italian Catholic Diocese of Piacenza-Bobbio has existed since 1989. In northern Italy, it is a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Modena-Nonantola. The historic Diocese of Piacenza was combined with the territory of the diocese of Bobbio-San Colombano, which was briefly united with the archdiocese of Genoa.

Anscar was a magnate in the Kingdom of Italy who served as Count of Pavia, Margrave of Ivrea (929–36) and Duke of Spoleto (936–40). He is sometimes numbered "Anscar II" to distinguish him from his grandfather, Anscar I of Ivrea. Described by Liutprand of Cremona as courageous and impulsive, he died in the battle of Spoleto.

Milo was the Count of Verona from 931 until 955. He was a vassal of four successive kings of Italy from 910. Under Berengar I he became a courtier (familiaris) and by 924 head of the bodyguard. By 927 he had expanded his landholdings to have vassals of his own. Under Hugh, he revolted twice but kept his position in Verona. Under Berengar II, he was raised to the rank of margrave (marchio) in 953.

Gandulf or Gandolf was a Frankish nobleman in the medieval kingdom of Italy. He rose from relatively low rank to become the count of Piacenza and finally a marchio (marquis). He is an ancestor of the Da Palazzo family.

Adela of Milan was a northern Italian noblewoman. Through her marriage to Albert Azzo I, Margrave of Milan, Adela was Margravine of Milan.

References

- 1 2 3 François Bougard, "Entre Gandolfinigi et Obertenghi: les comtes de Plaisance aux Xe et XIe siècles", Mélanges de l'Ecole française de Rome: Moyen-Âge, 101,1 (1989), pp. 11–66.

- ↑ Charles E. Odegaard, "The Empress Engelberge", Speculum , 26, 1 (1951), pp. 77–103, at p. 88.

- ↑ Alexander O'Hara and Faye Taylor, "Aristocratic and Monastic Conflict in Tenth-Century Italy: The Case of Bobbio and the Miracula sancti Columbani", Viator, 44, 3 (2013), pp. 43–62.

- ↑ Piacenza entry (in Italian) by Mario Longhena, Alda Levi Spinazzola, Arturo Pettorelli, Luigi Pairig, Tammaro De Marinis and Natale Carotti in the Enciclopedia italiana (1935).

- ↑ Chris Wickham, Medieval Rome: Stability and Crisis of a City, 900–1150 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 253.

- ↑ John W. Barker and Christopher Kleinhenz, "Piacenza", in Christopher Kleinhenz, ed., Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia (New York and London: Routledge, 2004), pp. 892–93.