Cryptozoology is a pseudoscience and subculture that searches for and studies unknown, legendary, or extinct animals whose present existence is disputed or unsubstantiated, particularly those popular in folklore, such as Bigfoot, the Loch Ness Monster, Yeti, the chupacabra, the Jersey Devil, or the Mokele-mbembe. Cryptozoologists refer to these entities as cryptids, a term coined by the subculture. Because it does not follow the scientific method, cryptozoology is considered a pseudoscience by mainstream science: it is neither a branch of zoology nor of folklore studies. It was originally founded in the 1950s by zoologists Bernard Heuvelmans and Ivan T. Sanderson.

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable claims; reliance on confirmation bias rather than rigorous attempts at refutation; lack of openness to evaluation by other experts; absence of systematic practices when developing hypotheses; and continued adherence long after the pseudoscientific hypotheses have been experimentally discredited. It is not the same as junk science.

Skepticism, also spelled scepticism in British English, is a questioning attitude or doubt toward knowledge claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. For example, if a person is skeptical about claims made by their government about an ongoing war then the person doubts that these claims are accurate. In such cases, skeptics normally recommend not disbelief but suspension of belief, i.e. maintaining a neutral attitude that neither affirms nor denies the claim. This attitude is often motivated by the impression that the available evidence is insufficient to support the claim. Formally, skepticism is a topic of interest in philosophy, particularly epistemology.

The Skeptic's Dictionary is a collection of cross-referenced skeptical essays by Robert Todd Carroll, published on his website skepdic.com and in a printed book. The skepdic.com site was launched in 1994 and the book was published in 2003 with nearly 400 entries. As of January 2011 the website has over 700 entries. A comprehensive single-volume guides to skeptical information on pseudoscientific, paranormal, and occult topics, the bibliography contains some seven hundred references for more detailed information. According to the back cover of the book, the on-line version receives approximately 500,000 hits per month.

Scientism is the view that science and the scientific method are the best or only way to render truth about the world and reality.

Scientific skepticism or rational skepticism, sometimes referred to as skeptical inquiry, is a position in which one questions the veracity of claims lacking empirical evidence. In practice, the term most commonly refers to the examination of claims and theories that appear to be beyond mainstream science, rather than the routine discussions and challenges among scientists. Scientific skepticism differs from philosophical skepticism, which questions humans' ability to claim any knowledge about the nature of the world and how they perceive it, and the similar but distinct methodological skepticism, which is a systematic process of being skeptical about the truth of one's beliefs.

Michael Brant Shermer is an American science writer, historian of science, executive director of The Skeptics Society, and founding publisher of Skeptic magazine, a publication focused on investigating pseudoscientific and supernatural claims. The author of over a dozen books, Shermer is known for engaging in debates on pseudoscience and religion in which he emphasizes scientific skepticism.

Duane Tolbert Gish was an American biochemist and a prominent member of the creationist movement. A young Earth creationist, Gish was a former vice-president of the Institute for Creation Research (ICR) and the author of numerous publications about creation science.

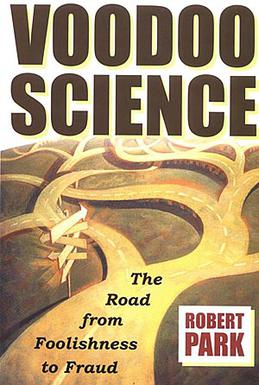

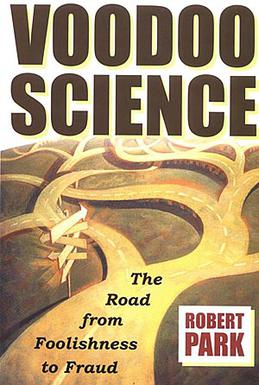

Voodoo Science: The Road from Foolishness to Fraud is a book published in 2000 by physics professor Robert L. Park, critical of research that falls short of adhering to the scientific method. Other people have used the term "voodoo science", but amongst academics it is most closely associated with Park. Park offers no explanation as to why he appropriated the word voodoo to describe the four categories detailed below. The book is critical of, among other things, homeopathy, cold fusion and the International Space Station.

Robert Lee Park was an American emeritus professor of physics at the University of Maryland, College Park, and a former director of public information at the Washington office of the American Physical Society. Park was most noted for his critical commentaries on alternative medicine and pseudoscience, as well as his criticism of how legitimate science is distorted or ignored by the media, some scientists, and public policy advocates as expressed in his book Voodoo Science. He was also noted for his preference for robotic over crewed space exploration.

The Skeptics Society is a nonprofit, member-supported organization devoted to promoting scientific skepticism and resisting the spread of pseudoscience, superstition, and irrational beliefs. The Skeptics Society was co-founded by Michael Shermer and Pat Linse as a Los Angeles-area skeptical group to replace the defunct Southern California Skeptics. After the success of its Skeptic magazine, introduced in early 1992, it became a national and then international organization. Their stated mission "is the investigation of science and pseudoscience controversies, and the promotion of critical thinking."

Skeptic, colloquially known as Skeptic magazine, is a quarterly science education and science advocacy magazine published internationally by The Skeptics Society, a nonprofit organization devoted to promoting scientific skepticism and resisting the spread of pseudoscience, superstition, and irrational beliefs. First published in 1992, the magazine had a circulation of over 40,000 subscribers in 2000.

Courtney Brown is an American political scientist and parapsychologist who is an associate professor in the political science department at Emory University. He is known for promoting the use of nonlinear mathematics in social scientific research, and as a proponent of remote viewing, a form of extrasensory perception.

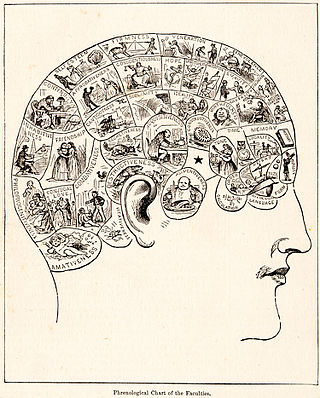

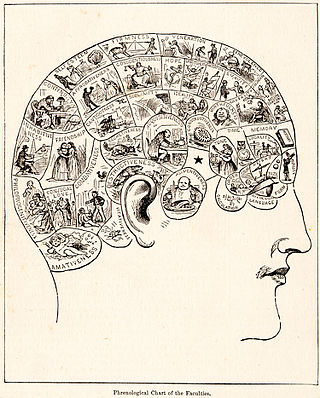

The history of pseudoscience is the study of pseudoscientific theories over time. A pseudoscience is a set of ideas that presents itself as science, while it does not meet the criteria to properly be called such.

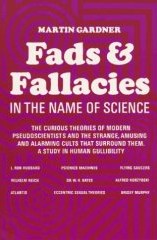

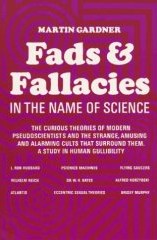

Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science (1957)—originally published in 1952 as In the Name of Science: An Entertaining Survey of the High Priests and Cultists of Science, Past and Present—was Martin Gardner's second book. A survey of what it described as pseudosciences and cult beliefs, it became a founding document in the nascent scientific skepticism movement. Michael Shermer said of it: "Modern skepticism has developed into a science-based movement, beginning with Martin Gardner's 1952 classic".

Criticism of religion involves criticism of the validity, concept, or ideas of religion.

Antireligion is opposition to religion or traditional religious beliefs and practices. It involves opposition to organized religion, religious practices or religious institutions. The term antireligion has also been used to describe opposition to specific forms of supernatural worship or practice, whether organized or not. The Soviet Union adopted the political ideology of Marxism–Leninism and by extension the policy of state atheism which opposed the growth of religions.

Gullibility is a failure of social intelligence in which a person is easily tricked or manipulated into an ill-advised course of action. It is closely related to credulity, which is the tendency to believe unlikely propositions that are unsupported by evidence.

The Science Network (TSN) is a non-profit virtual forum dedicated to science and its impact on society. It was initially conceived in 2003 by Roger Bingham and Terry Sejnowski as a cable science TV network modeled on C-SPAN. TSN later became a global digital platform hosting videos of lectures from scientific meetings and long form one-on-one conversations with prominent scientists and communicators of science, including Neil deGrasse Tyson, V.S. Ramachandran, Helen S. Mayberg, and Barbara Landau. TSN has also sponsored and co-sponsored scientific forums, such as Stem cells: science, ethics and politics at the crossroads, held at the Salk Institute in 2004 and the Beyond Belief conference series.

A superstition is any belief or practice considered by non-practitioners to be irrational or supernatural, attributed to fate or magic, perceived supernatural influence, or fear of that which is unknown. It is commonly applied to beliefs and practices surrounding luck, amulets, astrology, fortune telling, spirits, and certain paranormal entities, particularly the belief that future events can be foretold by specific unrelated prior events.