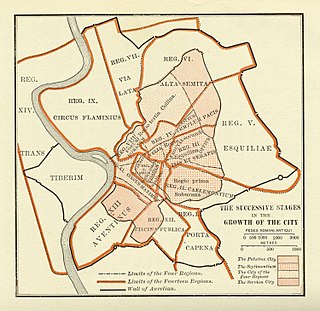

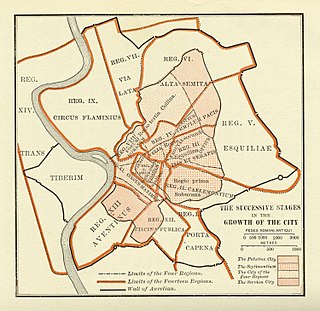

The Roman Kingdom was the earliest period of Roman history when the city and its territory were ruled by kings. According to oral accounts, the Roman Kingdom began with the city's founding c. 753 BC, with settlements around the Palatine Hill along the river Tiber in central Italy, and ended with the overthrow of the kings and the establishment of the Republic c. 509 BC.

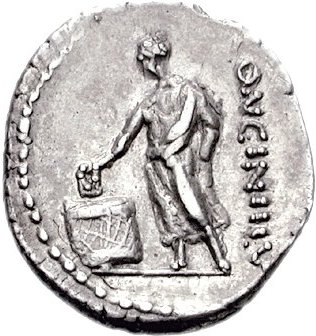

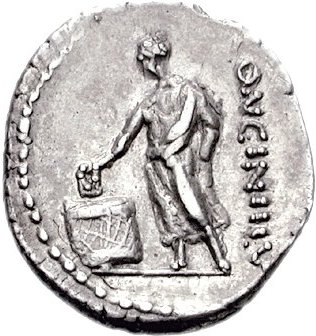

The pontifex maximus was the chief high priest of the College of Pontiffs in ancient Rome. This was the most important position in the ancient Roman religion, open only to patricians until 254 BC, when a plebeian first occupied this post. Although in fact the most powerful office in the Roman priesthood, the pontifex maximus was officially ranked fifth in the ranking of the highest Roman priests, behind the rex sacrorum and the flamines maiores.

The legislative assemblies of the Roman Republic were political institutions in the ancient Roman Republic. According to the contemporary historian Polybius, it was the people who had the final say regarding the election of magistrates, the enactment of Roman laws, the carrying out of capital punishment, the declaration of war and peace, and the creation of alliances. Under the Constitution of the Roman Republic, the people held the ultimate source of sovereignty.

The College of Pontiffs was a body of the ancient Roman state whose members were the highest-ranking priests of the state religion. The college consisted of the pontifex maximus and the other pontifices, the rex sacrorum, the fifteen flamens, and the Vestals. The College of Pontiffs was one of the four major priestly colleges; originally their responsibility was limited to supervising both public and private sacrifices, but as time passed their responsibilities increased. The other colleges were the augures, the quindecimviri sacris faciundis , and the epulones.

In ancient Roman religion, the rex sacrorum was a senatorial priesthood reserved for patricians. Although in the historical era, the pontifex maximus was the head of Roman state religion, Festus says that in the ranking of the highest Roman priests, the rex sacrorum was of highest prestige, followed by the flamines maiores and the pontifex maximus. The rex sacrorum was based in the Regia.

A Roman dictator was an extraordinary magistrate in the Roman Republic endowed with full authority to resolve some specific problem to which he had been assigned. He received the full powers of the state, subordinating the other magistrates, consuls included, for the specific purpose of resolving that issue, and that issue only, and then dispensing with those powers forthwith.

The Conflictof the Orders, sometimes referred to as the Struggle of the Orders, was a political struggle between the plebeians (commoners) and patricians (aristocrats) of the ancient Roman Republic lasting from 500 BC to 287 BC in which the plebeians sought political equality with the patricians. It played a major role in the development of the Constitution of the Roman Republic. Shortly after the founding of the Republic, this conflict led to a secession from Rome by Plebeians to the Sacred Mount at a time of war. The result of this first secession was the creation of the office of plebeian tribune, and with it the first acquisition of real power by the plebeians.

The interrex was literally a ruler "between kings" during the Roman Kingdom and the Roman Republic. He was in effect a short-term regent.

The Concilium Plebis was the principal assembly of the common people of the ancient Roman Republic. It functioned as a legislative/judicial assembly, through which the plebeians (commoners) could pass legislation, elect plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles, and try judicial cases. The Plebeian Council was originally organized on the basis of the Curia but in 471 BC adopted an organizational system based on residential districts or tribes. The Plebeian Council usually met in the well of the Comitium and could only be convoked by the tribune of the plebs. The patricians were excluded from the Council.

The Curiate Assembly was the principal assembly that evolved in shape and form over the course of the Roman Kingdom until the Comitia Centuriata organized by Servius Tullius. During these first decades, the people of Rome were organized into thirty units called "Curiae". The Curiae were ethnic in nature, and thus were organized on the basis of the early Roman family, or, more specifically, on the basis of the thirty original patrician (aristocratic) clans. The Curiae formed an assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial purposes. The Curiate Assembly passed laws, elected Consuls, and tried judicial cases. Consuls always presided over the assembly. While plebeians (commoners) could participate in this assembly, only the patricians could vote.

Lucius Papirius Cursor was a celebrated politician and general of the early Roman Republic, who was five times consul, three times magister equitum, and twice dictator. He was the most important Roman commander during the Second Samnite War, during which he received three triumphs.

A tribus, or tribe, was a division of the Roman people for military, censorial, and voting purposes. When constituted in the comitia tributa, the tribes were the voting units of a legislative assembly of the Roman Republic.

Publius Licinius Crassus Dives was consul in 205 BC with Scipio Africanus; he was also Pontifex Maximus since 213 or 212 BC, and held several other important positions. Licinius Crassus is mentioned several times in Livy's Histories. He is first mentioned in connection with his surprising election as Pontifex Maximus, and then several times since in various other capacities.

The constitution of the Roman Republic was a set of uncodified norms and customs which, together with various written laws, guided the procedural governance of the Roman Republic. The constitution emerged from that of the Roman kingdom, evolved substantively and significantly—almost to the point of unrecognisability—over the almost five hundred years of the republic. The collapse of republican government and norms from 133 BC would lead to the rise of Augustus and his principate.

The Roman Assemblies were institutions in ancient Rome. They functioned as the machinery of the Roman legislative branch, and thus passed all legislation. Since the assemblies operated on the basis of a direct democracy, ordinary citizens, and not elected representatives, would cast all ballots. The assemblies were subject to strong checks on their power by the executive branch and by the Roman Senate. Laws were passed by Curia, Tribes, and century.

The Constitution of the Roman Kingdom was an unwritten set of guidelines and principles originating mainly through precedent. During the years of the Roman Kingdom, the constitutional arrangement was centered on the king, who had the power to appoint assistants, and delegate to them their specific powers. The Roman Senate, which was dominated by the aristocracy, served as the advisory council to the king. Often, the king asked the Senate to vote on various matters, but he was free to ignore any advice they gave him. The king could also request a vote on various matters by the popular assembly, which he was also free to ignore. The popular assembly functioned as a vehicle through which the People of Rome could express their opinions. In it, the people were organized according to their respective curiae. However, the popular assembly did have other functions. For example, it was a forum used by citizens to hear announcements. It could also serve as a trial court for both civil and criminal matters.

The Senate of the Roman Kingdom was a political institution in the ancient Roman Kingdom. The word senate derives from the Latin word senex, which means "old man". Therefore, senate literally means "board of old men" and translates as "Council of Elders". The prehistoric Indo-Europeans who settled Rome in the centuries before the legendary founding of Rome in 753 BC were structured into tribal communities. These tribal communities often included an aristocratic board of tribal elders, who were vested with supreme authority over their tribe. The early tribes that had settled along the banks of the Tiber eventually aggregated into a loose confederation, and later formed an alliance for protection against invaders.

The Legislative Assemblies of the Roman Kingdom were political institutions in the ancient Roman Kingdom. While one assembly, the Curiate Assembly, had some legislative powers, these powers involved nothing more than a right to symbolically ratify decrees issued by the king. The functions of the other assembly, the Calate Assembly, was purely religious. During the years of the kingdom, the People of Rome were organized on the basis of units called curiae. All of the People of Rome were divided amongst a total of thirty curia, and membership in an individual curia was hereditary. Each member of a particular family belonged to the same curia. Each curia had an organization similar to that of the early Roman family, including specific religious rites and common festivals. These curia were the basic units of division in the two popular assemblies. The members in each curia would vote, and the majority in each curia would determine how that curia voted before the assembly. Thus, a majority of the curia was needed during any vote before either the Curiate Assembly or the Calate Assembly.

Aulus Sempronius Atratinus was a Roman Republican politician during the beginning of the 5th century BC. He served as Consul of Rome in 497 BC and again in 491 BC. He was of the patrician branch of his gens although the Sempronia gens also included certain plebeian families.

Gaius Julius Iulus was a member of the Roman gens Julia, and was nominated dictator in 352 BC.