Related Research Articles

Jupiter, also known as Jove, is the god of the sky and thunder, and king of the gods in ancient Roman religion and mythology. Jupiter was the chief deity of Roman state religion throughout the Republican and Imperial eras, until Christianity became the dominant religion of the Empire. In Roman mythology, he negotiates with Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, to establish principles of Roman religion such as offering, or sacrifice.

Vesta is the virgin goddess of the hearth, home, and family in Roman religion. She was rarely depicted in human form, and was more often represented by the fire of her temple in the Forum Romanum. Entry to her temple was permitted only to her priestesses, the Vestal Virgins. Their virginity was deemed essential to Rome's survival; if found guilty of inchastity, they were buried or entombed alive. As Vesta was considered a guardian of the Roman people, her festival, the Vestalia, was regarded as one of the most important Roman holidays. During the Vestalia privileged matrons walked barefoot through the city to the temple, where they presented food-offerings. Such was Vesta's importance to Roman religion that following the rise of Christianity, hers was one of the last non-Christian cults still active, until it was forcibly disbanded by the Christian emperor Theodosius I in AD 391.

In Roman mythology and religion, Quirinus is an early god of the Roman state. In Augustan Rome, Quirinus was also an epithet of Janus, as Janus Quirinus.

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Janus is the god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, frames, and endings. He is usually depicted as having two faces. The month of January is named for Janus (Ianuarius). According to ancient Roman farmers' almanacs, Juno was mistaken as the tutelary deity of the month of January, but Juno is the tutelary deity of the month of June.

Curia in ancient Rome referred to one of the original groupings of the citizenry, eventually numbering 30, and later every Roman citizen was presumed to belong to one. While they originally likely had wider powers, they came to meet for only a few purposes by the end of the Republic: to confirm the election of magistrates with imperium, to witness the installation of priests, the making of wills, and to carry out certain adoptions.

Festivals in ancient Rome were a very important part in Roman religious life during both the Republican and Imperial eras, and one of the primary features of the Roman calendar. Feriae were either public (publicae) or private (privatae). State holidays were celebrated by the Roman people and received public funding. Games (ludi), such as the Ludi Apollinares, were not technically feriae, but the days on which they were celebrated were dies festi, holidays in the modern sense of days off work. Although feriae were paid for by the state, ludi were often funded by wealthy individuals. Feriae privatae were holidays celebrated in honor of private individuals or by families. This article deals only with public holidays, including rites celebrated by the state priests of Rome at temples, as well as celebrations by neighborhoods, families, and friends held simultaneously throughout Rome.

The Robigalia was a festival in ancient Roman religion held April 25, named for the god Robigus. Its main ritual was a dog sacrifice to protect grain fields from disease. Games (ludi) in the form of "major and minor" races were held. The Robigalia was one of several agricultural festivals in April to celebrate and vitalize the growing season, but the darker sacrificial elements of these occasions are also fraught with anxiety about crop failure and the dependence on divine favor to avert it.

The Floralia was a festival in ancient Roman religious practice in honor of the goddess Flora, held on 27 April during the Republican era, or 28 April in the Julian calendar. The festival included Ludi Florae, the "Games of Flora", which lasted for six days under the empire.

In Roman religion, Terminus was the god who protected boundary markers; his name was the Latin word for such a marker. Sacrifices were performed to sanctify each boundary stone, and landowners celebrated a festival called the "Terminalia" in Terminus' honor each year on February 23. The Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill was thought to have been built over a shrine to Terminus, and he was occasionally identified as an aspect of Jupiter under the name "Jupiter Terminalis".

Juno was an ancient Roman goddess, the protector and special counsellor of the state. She was equated to Hera, queen of the gods in Greek mythology and a goddess of love and marriage. A daughter of Saturn and Ops, she was the sister and wife of Jupiter and the mother of Mars, Vulcan, Bellona, Lucina and Juventas. Like Hera, her sacred animal was the peacock. Her Etruscan counterpart was Uni, and she was said to also watch over the women of Rome. As the patron goddess of Rome and the Roman Empire, Juno was called Regina ("Queen") and was a member of the Capitoline Triad, centered on the Capitoline Hill in Rome, and also including Jupiter, and Minerva, goddess of wisdom.

In ancient Roman religion and mythology, Tellus Mater or Terra Mater is the personification of the Earth. Although Tellus and Terra are hardly distinguishable during the Imperial era, Tellus was the name of the original earth goddess in the religious practices of the Republic or earlier. The scholar Varro (1st century BC) lists Tellus as one of the di selecti, the twenty principal gods of Rome, and one of the twelve agricultural deities. She is regularly associated with Ceres in rituals pertaining to the earth and agricultural fertility.

Februarius, fully Mensis Februarius, was the shortest month of the Roman calendar from which the Julian and Gregorian month of February derived. It was eventually placed second in order, preceded by Ianuarius and followed by Martius. In the oldest Roman calendar, which the Romans believed to have been instituted by their legendary founder Romulus, March was the first month, and the calendar year had only ten months in all. Ianuarius and Februarius were supposed to have been added by Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, originally at the end of the year. It is unclear when the Romans reset the course of the year so that January and February came first.

A tribus, or tribe, was a division of the Roman people for military, censorial, and voting purposes. When constituted in the comitia tributa, the tribes were the voting units of a legislative assembly of the Roman Republic.

The Fasti, sometimes translated as The Book of Days or On the Roman Calendar, is a six-book Latin poem written by the Roman poet Ovid and published in AD 8. Ovid is believed to have left the Fasti incomplete when he was exiled to Tomis by the emperor Augustus in 8 AD. Written in elegiac couplets and drawing on conventions of Greek and Latin didactic poetry, the Fasti is structured as a series of eye-witness reports and interviews by the first-person vates with Roman deities, who explain the origins of Roman holidays and associated customs—often with multiple aetiologies. The poem is a significant, and in some cases unique, source of fact in studies of religion in ancient Rome; and the influential anthropologist and ritualist J.G. Frazer translated and annotated the work for the Loeb Classical Library series. Each book covers one month, January through June, of the Roman calendar, and was written several years after Julius Caesar replaced the old system of Roman time-keeping with what would come to be known as the Julian calendar.

Vestalia was a Roman religious festival in honor of Vesta, the goddess of the hearth and the burning continuation of the sacred fire of Rome. It was held from 7-15 June.

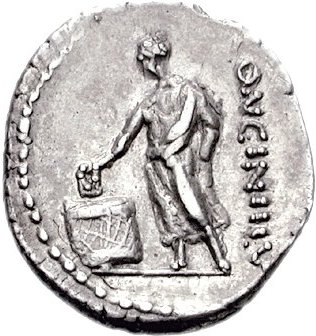

In ancient Roman religion, Fornax was the divine personification of the oven (fornāx), the patroness of bakers, and a goddess of baking. She ensured that the heat of ovens did not get hot enough to burn the corn or bread. People would pray to Fornax for help whilst baking. Her festival, the Fornacalia, was celebrated on February 17 among the thirty curiae, the most ancient divisions of the city made by Romulus from the original three tribes of Rome. The Fornacalia was the second of two festivals involving the curiae, the other being the Fordicidia on April 19. The goddess was probably conceived of to explain the festival, which was instituted for toasting the spelt used to bake sacrificial cakes. Her role was eventually merged with the goddess Vesta.

The curio maximus was an obscure priesthood in ancient Rome that had oversight of the curiae, groups of citizens loosely affiliated within what was originally a tribe. Each curia was led by a curio, who was admitted only after the age of 50 and held his office for life. The curiones were required to be in good health and without physical defect, and could not hold any other civil or military office; the pool of willing candidates was thus neither large nor eager. In the early Republic, the curio maximus was always a patrician, and officiated as the senior interrex. The earliest curio maximus identified as such is Servius Sulpicius, who held the office in 463. The first plebeian to hold the office was elected in 209 BC.

In ancient Roman religion, the Flamen Quirinalis was the flamen or high priest of the god Quirinus. He was one of the three flamines maiores, third in order of importance after the Flamen Dialis and the Flamen Martialis. Like the other two high priests, he was subject to numerous ritual taboos, such as not being allowed to touch metal, ride a horse, or spend the night outside Rome. His wife functioned as an assistant priestess with the title Flaminicia Quirinalis.

In ancient Roman religion, the Fordicidia was a festival of fertility, held on the Ides of April, that pertained to farming and animal husbandry. It involved the sacrifice of a pregnant cow to Tellus, the ancient Roman goddess of the Earth, in proximity to the festival of Ceres (Cerealia) on April 19.

References

- ↑ Varro, On the Latin Language, 6.13

- ↑ Fastorum libri sex. Cambridge University Press. 5 March 2015. p. 430. ISBN 978-1-108-08247-1.

- ↑ Paris, John Ayrton (2013). Philosophy in Sport Made Science in Earnest: Being an Attempt to Illustrate the First Principles of Natural Philosophy by the Aid of the Popular Toys and Sports. Cambridge University Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-1-108-05740-0.

- ↑ Ovid, Fasti , 2.525-6

- ↑ Note on p. 186 of the Loeb edition of Varro's , On the Latin Language, Vol 1

- ↑ Roy, Christian (2005). Traditional Festivals: A Multicultural Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-57607-089-5.

- ↑ Smith, C. J. (2006). The Roman Clan: The Gens from Ancient Ideology to Modern Anthropology. Cambridge University Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-139-45087-4.

- ↑ Mayeske, Betty (1972). Bakeries, Bakers, And Bread At Pompeii: A Study in Social and Economic History (Thesis). OCLC 1067729413.

- ↑ Rousseau, G. S. (1979). "Ephebi, Epigoni, and Fornacalia: Some Meditations on the Contemporary Historiography of the Eighteenth Century". The Eighteenth Century. 20 (3): 203–226. JSTOR 41467196. PMID 11614432. ProQuest 1306612456.

- ↑ Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther, eds. (2012). "Fornacalia". The Oxford Classical Dictionary. OUP Oxford. p. 585. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8.

- ↑ Ovid, Fasti , 2.527-30

- ↑ DiLuzio, Meghan J. (2020). A Place at the Altar: Priestesses in Republican Rome. Princeton University Press. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-691-20232-7.

- ↑ Smith, Christopher J. (2012). "Fornacalia". The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah17168. ISBN 978-1-4051-7935-5.

- ↑ Phillips, C. Robert (2015). "Fornacalia". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.2705. ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5.

- ↑ Ovid, Fasti , 2.531-2

- ↑ Cornell, The Beginnings of Rome, p. 115

- ↑ Cornell, Tim (2012). The Beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (c.1000–264 BC). Routledge. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-136-75495-1.

- ↑ Smith, W., Wayte, W., Marindin, G. E., (Eds), A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890): Fornacalia