Related Research Articles

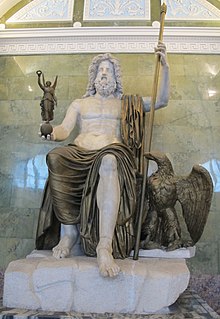

Jupiter, also known as Jove, is the god of the sky and thunder and king of the gods in Ancient Roman religion and mythology. Jupiter was the chief deity of Roman state religion throughout the Republican and Imperial eras, until Christianity became the dominant religion of the Empire. In Roman mythology, he negotiates with Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, to establish principles of Roman religion such as offering, or sacrifice.

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Luna is the divine embodiment of the Moon. She is often presented as the female complement of the Sun, Sol, conceived of as a god. Luna is also sometimes represented as an aspect of the Roman triple goddess, along with Proserpina and Hecate. Luna is not always a distinct goddess, but sometimes rather an epithet that specializes a goddess, since both Diana and Juno are identified as moon goddesses.

Neptune is the god of freshwater and the sea in Roman religion. He is the counterpart of the Greek god Poseidon. In the Greek-influenced tradition, Neptune is the brother of Jupiter and Pluto; the brothers preside over the realms of Heaven, the earthly world, and the Underworld. Salacia is his wife.

Saturnalia was an ancient Roman festival and holiday in honour of the god Saturn, held on 17 December of the Julian calendar and later expanded with festivities through to 23 December. The holiday was celebrated with a sacrifice at the Temple of Saturn, in the Roman Forum, and a public banquet, followed by private gift-giving, continual partying, and a carnival atmosphere that overturned Roman social norms: gambling was permitted, and masters provided table service for their slaves as it was seen as a time of liberty for both slaves and freedmen alike. A common custom was the election of a "King of the Saturnalia", who would give orders to people, which were to be followed and preside over the merrymaking. The gifts exchanged were usually gag gifts or small figurines made of wax or pottery known as sigillaria. The poet Catullus called it "the best of days".

Festivals in ancient Rome were a very important part of Roman religious life during both the Republican and Imperial eras, and one of the primary features of the Roman calendar. Feriae were either public (publicae) or private (privatae). State holidays were celebrated by the Roman people and received public funding. Games (ludi), such as the Ludi Apollinares, were not technically feriae, but the days on which they were celebrated were dies festi, holidays in the modern sense of days off work. Although feriae were paid for by the state, ludi were often funded by wealthy individuals. Feriae privatae were holidays celebrated in honor of private individuals or by families. This article deals only with public holidays, including rites celebrated by the state priests of Rome at temples, as well as celebrations by neighborhoods, families, and friends held simultaneously throughout Rome.

The Robigalia was a festival in ancient Roman religion held April 25, named for the god Robigus. Its main ritual was a dog sacrifice to protect grain fields from disease. Games (ludi) in the form of "major and minor" races were held. The Robigalia was one of several agricultural festivals in April to celebrate and vitalize the growing season, but the darker sacrificial elements of these occasions are also fraught with anxiety about crop failure and the dependence on divine favor to avert it.

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Tellus Mater or Terra Mater is a goddess of the earth. Although Tellus and Terra are hardly distinguishable during the Imperial era, Tellus was the name of the original earth goddess in the religious practices of the Republic or earlier. The scholar Varro (1st century BC) lists Tellus as one of the di selecti, the twenty principal gods of Rome, and one of the twelve agricultural deities. She is regularly associated with Ceres in rituals pertaining to the earth and agricultural fertility.

Februarius, fully Mensis Februarius, was the shortest month of the Roman calendar from which the Julian and Gregorian month of February derived. It was eventually placed second in order, preceded by Ianuarius and followed by Martius. In the oldest Roman calendar, which the Romans believed to have been instituted by their legendary founder Romulus, March was the first month, and the calendar year had only ten months in all. Ianuarius and Februarius were supposed to have been added by Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, originally at the end of the year. It is unclear when the Romans reset the course of the year so that January and February came first.

In ancient Roman religion, the Furrinalia was an annual festival held on 25 July to celebrate the rites (sacra) of the goddess Furrina. Varro notes that the festival was a public holiday (feriae publicae dies). Both the festival and the goddess had become obscure even to the Romans of the Late Republic; Varro notes that few people in his day even know her name. One of the fifteen flamines was assigned to her, indicating her archaic stature, and she had a sacred grove (lucus) on the Janiculum, which may have been the location of the festival. Furrina was associated with water, and the Furrinalia follows the Lucaria on 19 and 21 July and the Neptunalia on 23 July, a grouping that may reflect a concern for summer drought.

In ancient Roman religion, the Epulum Jovis was a sumptuous ritual feast offered to Jove on the Ides of September and a smaller feast on the Ides of November. It was celebrated during the Ludi Romani and the Ludi Plebeii.

In ancient Roman religion, a lūcus is a sacred grove.

An Agonalia or Agonia was an obscure archaic religious observance celebrated in ancient Rome several times a year, in honor of various divinities. Its institution, like that of other religious rites and ceremonies, was attributed to Numa Pompilius, the semi-legendary second king of Rome. Ancient calendars indicate that it was celebrated regularly on January 9, May 21, and December 11.

Saturn was a god in ancient Roman religion, and a character in Roman mythology. He was described as a god of generation, dissolution, plenty, wealth, agriculture, periodic renewal and liberation. Saturn's mythological reign was depicted as a Golden Age of plenty and peace. After the Roman conquest of Greece, he was conflated with the Greek Titan Cronus. Saturn's consort was his sister Ops, with whom he fathered Jupiter, Neptune, Pluto, Juno, Ceres and Vesta.

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Mars was the god of war and also an agricultural guardian, a combination characteristic of early Rome. He was the son of Jupiter and Juno, and he was the most prominent of the military gods in the religion of the Roman army. Most of his festivals were held in March, the month named for him, and in October, which began the season for military campaigning and ended the season for farming.

In ancient Roman religion, a sacellum is a small shrine. The word is a diminutive from sacer. The numerous sacella of ancient Rome included both shrines maintained on private properties by families, and public shrines. A sacellum might be square or round.

In ancient Roman religion, the Flamen Quirinalis was the flamen or high priest of the god Quirinus. He was one of the three flamines maiores, third in order of importance after the Flamen Dialis and the Flamen Martialis. Like the other two high priests, he was subject to numerous ritual taboos, such as not being allowed to touch metal, ride a horse, or spend the night outside Rome. His wife functioned as an assistant priestess with the title Flaminicia Quirinalis.

The vocabulary of ancient Roman religion was highly specialized. Its study affords important information about the religion, traditions and beliefs of the ancient Romans. This legacy is conspicuous in European cultural history in its influence on later juridical and religious vocabulary in Europe, particularly of the Western Church. This glossary provides explanations of concepts as they were expressed in Latin pertaining to religious practices and beliefs, with links to articles on major topics such as priesthoods, forms of divination, and rituals.

In ancient Roman religion, the Fordicidia was a festival of fertility, held two days after the Ides of April, that pertained to farming and animal husbandry. It involved the sacrifice of a pregnant cow to Tellus, the ancient Roman goddess of the Earth, in proximity to the festival of Ceres (Cerealia) on April 19.

The Amburbium was an ancient Roman festival for purifying the city; that is, a lustration (lustratio urbis). It took the form of a procession, perhaps along the old Servian Wall, though the length of 10 kilometers would seem impractical to circumambulate. If it was a distinct festival held annually, the most likely month is February, but no date is recorded and the ritual may have been performed as a "crisis rite" when needed.

References

- ↑ Varro, De lingua latina 6.3.

- ↑ Kurt Latte, Römische Religionsgeschicte (C.H. Beck, 1992), p. 88.

- ↑ Cato, On Agriculture 139; Robert E.A. Palmer, The Archaic Community of the Romans (Cambridge University Press, 2009), p. 106.

- ↑ Jörg Rüpke, Religion of the Romans (Polity Press, 2007, originally published in German 2001), p. 189

- ↑ As recorded by Festus: Lucaria festa in luco colebant Romani, qui permagnus inter viam Salariam et Tiberim fuit, pro eo, quod victi e Gallis fugientes e praelio ibi se occultaverint.

- ↑ William Warde Fowler, The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic (London, 1908), p. 182.

- ↑ Fowler, Roman Festivals, p. 183.

- ↑ Fowler, Roman Festivals, pp. 182–183.

- ↑ Ken Dowden, European Paganism: The Realities of Cult from Antiquity to the Middle Ages (Routledge, 2000), p. 107.

- ↑ Martin Henig, Religion in Roman Britain (Taylor & Francis, 1984, 2005), p. 15.

- ↑ Michael Lipka, Roman Gods: A Conceptual Approach (Brill, 2009), pp. 38–39

- ↑ Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.4.15.

- ↑ According to Julius Caesar, Bellum Gallicum 6.18, the Gauls regularly reckoned time by nights rather than days: "They compute the divisions of every season, not by the number of days, but of nights; they keep birthdays and the beginnings of months and years in such an order that the day follows the night" (spatia omnis temporis non numero dierum sed noctium finiunt; dies natales et mensum et annorum initia sic observant ut noctem dies subsequatur).

- ↑ Sarolta A. Takács, Vestal Virgins, Sibyls, and Matrons: Women in Roman Religion (University of Texas Press, 2008), p. 53.

- ↑ Robert Schilling, "Neptune," Roman and European Mythologies (University of Chicago Press, 1992, from the French edition of 1981), p. 138.