Fontus or Fons was a god of wells and springs in ancient Roman religion. A religious festival called the Fontinalia was held on October 13 in his honor. Throughout the city, fountains and wellheads were adorned with garlands.

In ancient Roman religion, the diiNovensiles or Novensides are collective deities of obscure significance found in inscriptions, prayer formulary, and both ancient and early-Christian literary texts.

In Roman mythology and religion, Quirinus is an early god of the Roman state. In Augustan Rome, Quirinus was also an epithet of Janus, as Janus Quirinus.

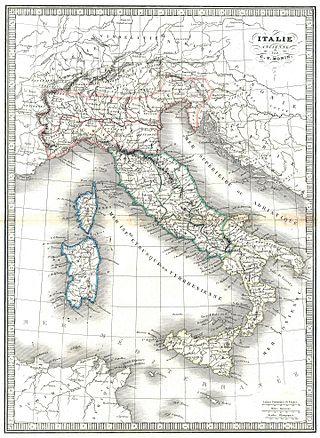

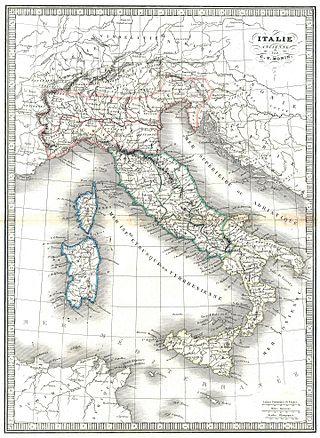

The Sabines were an Italic people who lived in the central Apennine Mountains of the ancient Italian Peninsula, also inhabiting Latium north of the Anio before the founding of Rome.

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Janus is the god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, frames, and endings. He is usually depicted as having two faces. The month of January is named for Janus (Ianuarius). According to ancient Roman farmers' almanacs, Juno was mistaken as the tutelary deity of the month of January, but Juno is the tutelary deity of the month of June.

The Salii, Salians, or Salian priests were the "leaping priests" of Mars in ancient Roman religion, supposed to have been introduced by King Numa Pompilius. They were twelve patrician youths dressed as archaic warriors with an embroidered tunic, a breastplate, a short red cloak, a sword, and a spiked headdress called an apex. They were charged with the twelve bronze shields called ancilia, which—like those of the Mycenaeans—resembled a figure eight. One of the shields was said to have fallen from heaven in the reign of King Numa and eleven copies were made to protect the identity of the sacred shield on the advice of the nymph Egeria, consort of Numa, who prophesied that wherever that shield was preserved, the people would be the dominant people of the earth.

Festivals in ancient Rome were a very important part in Roman religious life during both the Republican and Imperial eras, and one of the primary features of the Roman calendar. Feriae were either public (publicae) or private (privatae). State holidays were celebrated by the Roman people and received public funding. Games (ludi), such as the Ludi Apollinares, were not technically feriae, but the days on which they were celebrated were dies festi, holidays in the modern sense of days off work. Although feriae were paid for by the state, ludi were often funded by wealthy individuals. Feriae privatae were holidays celebrated in honor of private individuals or by families. This article deals only with public holidays, including rites celebrated by the state priests of Rome at temples, as well as celebrations by neighborhoods, families, and friends held simultaneously throughout Rome.

The Floralia was a festival in ancient Roman religious practice in honor of the goddess Flora, held on 27 April during the Republican era, or 28 April in the Julian calendar. The festival included Ludi Florae, the "Games of Flora", which lasted for six days under the empire.

In ancient Roman religion and mythology, Tellus Mater or Terra Mater is the personification of the Earth. Although Tellus and Terra are hardly distinguishable during the Imperial era, Tellus was the name of the original earth goddess in the religious practices of the Republic or earlier. The scholar Varro (1st century BC) lists Tellus as one of the di selecti, the twenty principal gods of Rome, and one of the twelve agricultural deities. She is regularly associated with Ceres in rituals pertaining to the earth and agricultural fertility.

The Equirria were two ancient Roman festivals of chariot racing, or perhaps horseback racing, held in honor of the god Mars, one 27 February and the other 14 March.

An Agonalia or Agonia was an obscure archaic religious observance celebrated in ancient Rome several times a year, in honor of various divinities. Its institution, like that of other religious rites and ceremonies, was attributed to Numa Pompilius, the semi-legendary second king of Rome. Ancient calendars indicate that it was celebrated regularly on January 9, May 21, and December 11.

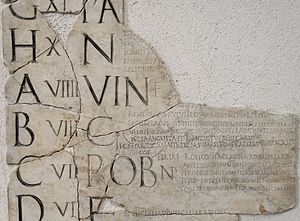

The Fasti, sometimes translated as The Book of Days or On the Roman Calendar, is a six-book Latin poem written by the Roman poet Ovid and published in AD 8. Ovid is believed to have left the Fasti incomplete when he was exiled to Tomis by the emperor Augustus in 8 AD. Written in elegiac couplets and drawing on conventions of Greek and Latin didactic poetry, the Fasti is structured as a series of eye-witness reports and interviews by the first-person vates with Roman deities, who explain the origins of Roman holidays and associated customs—often with multiple aetiologies. The poem is a significant, and in some cases unique, source of fact in studies of religion in ancient Rome; and the influential anthropologist and ritualist J.G. Frazer translated and annotated the work for the Loeb Classical Library series. Each book covers one month, January through June, of the Roman calendar, and was written several years after Julius Caesar replaced the old system of Roman time-keeping with what would come to be known as the Julian calendar.

Romulus was the legendary founder and first king of Rome. Various traditions attribute the establishment of many of Rome's oldest legal, political, religious, and social institutions to Romulus and his contemporaries. Although many of these traditions incorporate elements of folklore, and it is not clear to what extent a historical figure underlies the mythical Romulus, the events and institutions ascribed to him were central to the myths surrounding Rome's origins and cultural traditions.

In ancient Roman religion and mythology, Mars was the god of war and also an agricultural guardian, a combination characteristic of early Rome. He was the son of Jupiter and Juno, and was pre-eminent among the Roman army's military gods. Most of his festivals were held in March, the month named for him, and in October, the months which traditionally began and ended the season for both military campaigning and farming.

In ancient Roman religion, the Flamen Quirinalis was the flamen or high priest of the god Quirinus. He was one of the three flamines maiores, third in order of importance after the Flamen Dialis and the Flamen Martialis. Like the other two high priests, he was subject to numerous ritual taboos, such as not being allowed to touch metal, ride a horse, or spend the night outside Rome. His wife functioned as an assistant priestess with the title Flaminicia Quirinalis.

In ancient Roman religion, the Fordicidia was a festival of fertility, held on the Ides of April, that pertained to farming and animal husbandry. It involved the sacrifice of a pregnant cow to Tellus, the ancient Roman goddess of the Earth, in proximity to the festival of Ceres (Cerealia) on April 19.

The Aventine Triad is a modern term for the joint cult of the Roman deities Ceres, Liber and Libera. The cult was established c. 493 BC within a sacred district (templum) on or near the Aventine Hill, traditionally associated with the Roman plebs. Later accounts describe the temple building and rites as "Greek" in style. Some modern historians describe the Aventine Triad as a plebeian parallel and self-conscious antithesis to the Archaic Triad of Jupiter, Mars and Quirinus and the later Capitoline Triad of Jupiter, Minerva and Juno. The Aventine Triad, temple and associated ludi served as a focus of plebeian identity, sometimes in opposition to Rome's original ruling elite, the patricians.

Roman mythology is the body of myths of ancient Rome as represented in the literature and visual arts of the Romans. One of a wide variety of genres of Roman folklore, Roman mythology may also refer to the modern study of these representations, and to the subject matter as represented in the literature and art of other cultures in any period. Roman mythology draws from the mythology of the Italic peoples and ultimately from Proto-Indo-European mythology.

Aprilis or mensis Aprilis (April) was the second month of the ancient Roman calendar, following Martius (March) and preceding Maius (May). On the oldest Roman calendar that had begun with March, Aprilis was the second of ten months in the year. April had 29 days on calendars of the Roman Republic, with a day added to the month during the reform in the mid-40s BC that produced the Julian calendar.