All Souls' Day, also called The Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed, is a day of prayer and remembrance for the faithful departed, observed by Christians on 2 November. Through prayer, intercessions, alms and visits to cemeteries, people commemorate the poor souls in purgatory and gain them indulgences.

The liturgical year, also called the church year, Christian year or kalendar, consists of the cycle of liturgical days and seasons that determines when feast days, including celebrations of saints, are to be observed, and which portions of scripture are to be read.

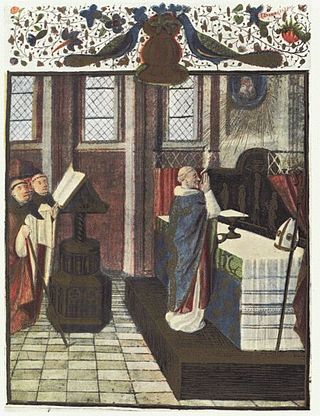

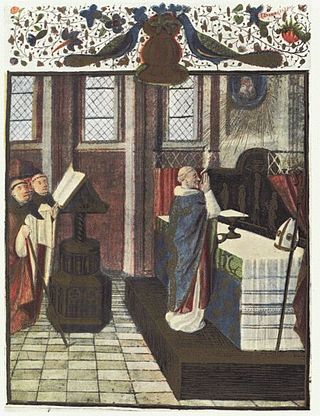

Mass is the main Eucharistic liturgical service in many forms of Western Christianity. The term Mass is commonly used in the Catholic Church, Western Rite Orthodoxy, Old Catholicism, and Independent Catholicism. The term is also used in some Lutheran churches, as well as in some Anglican churches, and on rare occasion by other Protestant churches.

Ash Wednesday is a holy day of prayer and fasting in many Western Christian denominations. It is preceded by Shrove Tuesday and marks the first day of Lent, the six weeks of penitence before Easter.

Maundy Thursday or Holy Thursday, among other names, is the day during Holy Week that commemorates the Washing of the Feet (Maundy) and Last Supper of Jesus Christ with the Apostles, as described in the canonical gospels.

Holy Week is the most sacred week in the liturgical year in Christianity. For all Christian traditions, it is a moveable observance. In Eastern Christianity, which also calls it Great Week, it is the week following Great Lent and Lazarus Saturday, starting on the evening of Palm Sunday and concluding on the evening of Great Saturday. In Western Christianity, Holy Week is the sixth and last week of Lent, beginning with Palm Sunday and concluding on Holy Saturday.

The Feast of Corpus Christi, also known as the Solemnity of the Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ, is a Christian liturgical solemnity celebrating the Real Presence of the Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity of Jesus in the elements of the Eucharist; it is observed by the Latin Church, in addition to certain Western Orthodox, Lutheran, and Anglican churches. Two months earlier, the institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper is observed on Maundy Thursday in a sombre atmosphere leading to Good Friday. The liturgy on that day also commemorates Christ's washing of the disciples' feet, the institution of the priesthood, and the agony in the Garden of Gethsemane.

Trinity Sunday is the first Sunday after Pentecost in the Western Christian liturgical calendar, and the Sunday of Pentecost in Eastern Christianity. Trinity Sunday celebrates the Christian doctrine of the Trinity, the three Persons of God: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Ember days are quarterly periods of prayer and fasting in the liturgical calendar of Western Christian churches. These fasts traditionally take place on the Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday of the weeks following St Lucy's Day, the first Sunday in Lent, Pentecost (Whitsun), and Holy Cross Day, though some areas follow a different pattern. The Catholic Church ended its practice of fasting on these days in 1966, and the Anglican Communion made fasting optional in 1976. Ordination ceremonies are often held on Ember Saturdays or the following Sunday.

The Paschal Triduum or Easter Triduum, Holy Triduum, or the Three Days, is the period of three days that begins with the liturgy on the evening of Maundy Thursday, reaches its high point in the Easter Vigil, and closes with evening prayer on Easter Sunday. It is a moveable observance recalling the Passion, Crucifixion, Death, burial, and Resurrection of Jesus, as portrayed in the canonical Gospels.

Litany, in Christian worship and some forms of Jewish worship, is a form of prayer used in services and processions, and consisting of a number of petitions. The word comes through Latin litania from Ancient Greek λιτανεία (litaneía), which in turn comes from λιτή (litḗ), meaning "prayer, supplication".

Eastertide or Paschaltide is a festal season in the liturgical year of Christianity that focuses on celebrating the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. Preceded by Lent, it begins on Easter Sunday, which initiates Easter Week in Western Christianity, and Bright Week in Eastern Christianity.

Christian liturgy is a pattern for worship used by a Christian congregation or denomination on a regular basis. The term liturgy comes from Greek and means "public work". Within Christianity, liturgies descending from the same region, denomination, or culture are described as ritual families.

The Easter Vigil, also called the Paschal Vigil, the Great Vigil of Easter, or Holy Saturday in the Easter Vigil on the Holy Night of Easter is a liturgy held in traditional Christian churches as the first official celebration of the Resurrection of Jesus. Historically, it is during this liturgy that people are baptized and that adult catechumens are received into full communion with the Church. It is held in the hours of darkness between sunset on Holy Saturday and sunrise on Easter Day – most commonly in the evening of Holy Saturday or midnight – and is the first celebration of Easter, days traditionally being considered to begin at sunset.

A procession is an organized body of people walking in a formal or ceremonial manner.

The Feast of the Transfiguration is celebrated by various Christian communities in honor of the transfiguration of Jesus. The origins of the feast are less than certain and may have derived from the dedication of three basilicas on Mount Tabor. The feast was present in various forms by the 9th century, and in the Western Church was made a universal feast celebrated on 6 August by Pope Callixtus III to commemorate the raising of the siege of Belgrade (1456).

"Octave" has two senses in Christian liturgical usage. In the first sense, it is the eighth day after a feast, reckoning inclusively, and so always falls on the same day of the week as the feast itself. The word is derived from Latin octava (eighth), with dies (day) understood. In the second sense, the term is applied to the whole period of these eight days, during which certain major feasts came to be observed.

The Mass is the central liturgical service of the Eucharist in the Catholic Church, in which bread and wine are consecrated and become the body and blood of Christ. As defined by the Church at the Council of Trent, in the Mass "the same Christ who offered himself once in a bloody manner on the altar of the cross, is present and offered in an unbloody manner". The Church describes the Mass as the "source and summit of the Christian life", and teaches that the Mass is a sacrifice, in which the sacramental bread and wine, through consecration by an ordained priest, become the sacrificial body, blood, soul, and divinity of Christ as the sacrifice on Calvary made truly present once again on the altar. The Catholic Church permits only baptised members in the state of grace to receive Christ in the Eucharist.

The Lutheran liturgical calendar is a listing which details the primary annual festivals and events that are celebrated liturgically by various Lutheran churches. The calendars of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada (ELCIC) are from the 1978 Lutheran Book of Worship and the calendar of the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod (LCMS) and the Lutheran Church–Canada (LCC) use the Lutheran Book of Worship and the 1982 Lutheran Worship. Elements unique to the ELCA have been updated from the Lutheran Book of Worship to reflect changes resulting from the publication of Evangelical Lutheran Worship in 2006. The elements of the calendar unique to the LCMS have also been updated from Lutheran Worship and the Lutheran Book of Worship to reflect the 2006 publication of the Lutheran Service Book.

A liturgical book, or service book, is a book published by the authority of a church body that contains the text and directions for the liturgy of its official religious services.