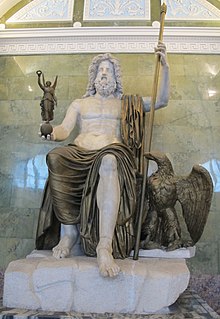

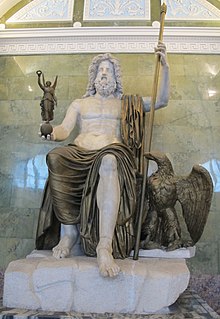

Jupiter, also known as Jove, is the god of the sky and thunder and king of the gods in Ancient Roman religion and mythology. Jupiter was the chief deity of Roman state religion throughout the Republican and Imperial eras, until Christianity became the dominant religion of the Empire. In Roman mythology, he negotiates with Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, to establish principles of Roman religion such as offering, or sacrifice.

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Luna is the divine embodiment of the Moon. She is often presented as the female complement of the Sun, Sol, conceived of as a god. Luna is also sometimes represented as an aspect of the Roman triple goddess, along with Proserpina and Hecate. Luna is not always a distinct goddess, but sometimes rather an epithet that specializes a goddess, since both Diana and Juno are identified as moon goddesses.

In Roman religion, Angerona or Angeronia was an old Roman goddess, whose name and functions are variously explained. She is sometimes identified with the goddess Feronia.

Mellona or Mellonia was an ancient Roman goddess said by St. Augustine to promote the supply of honey as Pomona did for apples and Bubona for cattle. Arnobius describes her as "a goddess important and powerful regarding bees, taking care of and protecting the sweetness of honey."

In ancient Roman religion, the diiNovensiles or Novensides are collective deities of obscure significance found in inscriptions, prayer formulary, and both ancient and early-Christian literary texts.

In ancient Roman religion, Strenua or Strenia was a goddess of the new year, purification, and wellbeing. She had a shrine (sacellum) and grove (lucus) at the top of the Via Sacra. Varro said she was a Sabine goddess. W.H. Roscher includes her among the indigitamenta, the lists of Roman deities maintained by priests to assure that the correct divinity was invoked in public rituals. The procession of the Argei began at her shrine.

Neptune is the god of freshwater and the sea in Roman religion. He is the counterpart of the Greek god Poseidon. In the Greek-influenced tradition, Neptune is the brother of Jupiter and Pluto; the brothers preside over the realms of Heaven, the earthly world, and the Underworld. Salacia is his wife.

The Robigalia was a festival in ancient Roman religion held April 25, named for the god Robigus. Its main ritual was a dog sacrifice to protect grain fields from disease. Games (ludi) in the form of "major and minor" races were held. The Robigalia was one of several agricultural festivals in April to celebrate and vitalize the growing season, but the darker sacrificial elements of these occasions are also fraught with anxiety about crop failure and the dependence on divine favor to avert it.

In ancient Roman religion, Averruncus or Auruncus is a god of averting harm. Aulus Gellius says that he is one of the potentially malignant deities who must be propitiated for their power to both inflict and withhold disaster from people and the harvests.

An Agonalia or Agonia was an obscure archaic religious observance celebrated in ancient Rome several times a year, in honor of various divinities. Its institution, like that of other religious rites and ceremonies, was attributed to Numa Pompilius, the semi-legendary second king of Rome. Ancient calendars indicate that it was celebrated regularly on January 9, May 21, and December 11.

The Acta Arvalia were the recorded protocols of the Arval Brothers (Arvales fratres), a priestly brotherhood (sodalitas) of ancient Roman religion.

Nenia Dea was an ancient funeral deity of Rome, who had a sanctuary outside of the Porta Viminalis. The cult of the Nenia is doubtlessly a very old one, but according to Georg Wissowa the location of Nenia's shrine (sacellum) outside of the center of early Rome indicates that she didn't belong to the earliest circle of Roman deities. In a different interpretation her shrine was located outside of the old city walls, because it had been custom for all gods connected to death or dying.

In ancient Roman religion, Mutunus Tutunus or Mutinus Titinus was a phallic marriage deity, in some respects equated with Priapus. His shrine was located on the Velian Hill, supposedly since the founding of Rome, until the 1st century BC.

In ancient Roman religion, Vagitanus or Vaticanus was one of a number of childbirth deities who influenced or guided some aspect of parturition, in this instance the newborn's crying. The name is related to the Latin noun vagitus, "crying, squalling, wailing," particularly by a baby or an animal, and the verb vagio, vagire. Vagitanus has thus been described as the god "who presided over the beginning of human speech," but a distinction should be made between the first cry and the first instance of articulate speech, in regard to which Fabulinus was the deity to invoke. Vagitanus has been connected to a remark by Pliny that only a human being is thrown naked onto the naked earth on his day of birth for immediate wails (vagitus) and weeping.

The Moles are goddesses who appear in an ancient Roman prayer formula in connection with Mars. The list of invocations given by Aulus Gellius pairs a god's name with a feminine nominative noun that personifies a quality or power of the god (Moles Martis, "Moles of Mars"). These pairings are often taken as "marriages" in the anthropomorphic mythological tradition. An inscription records a supplicatio Molibus Martis, supplication for the Moles of Mars.

Cornelius Labeo was an ancient Roman theologian and antiquarian who wrote on such topics as the Roman calendar and the teachings of Etruscan religion (Etrusca disciplina). His works survive only in fragments and testimonia. He has been dated "plausibly but not provably" to the 3rd century AD. Labeo has been called "the most important Roman theologian" after Varro, whose work seems to have influenced him strongly. He is usually considered a Neoplatonist.

Agenoria is a Roman goddess of activity (actus). Her name is presumably derived from the Latin verb agō, "to do, drive, go"; present participle agēns. She is named only by Augustine of Hippo, who places her among the deities who are concerned with childhood. She is thus one of the goddesses who endows the child with a developmental capacity, such as walking, singing, reasoning, and learning to count. W.H. Roscher includes Agenoria among the indigitamenta, the list of deities maintained by Roman priests to assure that the correct divinity was invoked for rituals.