The Lombards or Longobards were a Germanic people who conquered most of the Italian Peninsula between 568 and 774.

Anselm was the Lombard duke of Friuli (749–751) and the founding abbot of the monastery of Nonantula.

The Duchy of Benevento was the southernmost Lombard duchy in the Italian Peninsula that was centered in Benevento, a city in Southern Italy. Lombard dukes ruled Benevento from 571 to 774, when the Kingdom of the Lombards was conquered by the Kingdom of the Franks. Being cut off from the rest of the Lombard possessions by the papal Duchy of Rome, Benevento always had held some degree of independence. Only during the reigns of Grimoald and the kings from Liutprand on was the duchy closely tied to the Kingdom of the Lombards. After the fall of the in 774, the duchy became the sole Lombard territory which continued to exist as a rump state, maintaining its de facto independence for nearly 300 years as the Principality of Benevento.

Ratchis was the Duke of Friuli (739–744) and then King of the Lombards (744–749).

The Origo Gentis Langobardorum is a short, 7th-century AD Latin account offering a founding myth of the Longobard people. The first part describes the origin and naming of the Lombards, the following text more resembles a king-list, up until the rule of Perctarit (672–688).

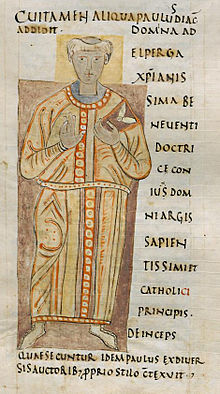

The History of the Lombards or the History of the Langobards is the chief work by Paul the Deacon, written in the late 8th century. This incomplete history in six books was written after 787 and at any rate no later than 796, maybe at Montecassino.

Arechis II was a Duke of Benevento, in Southern Italy. He sought to expand the Beneventos' influence into areas of Italy that were still under Byzantine control, but he also had to defend against Charlemagne, who had conquered northern Italy.

The Rule of the Dukes was an interregnum in the Lombard Kingdom of Italy (574/5–584/5) during which part of Italy was ruled by the Lombard dukes of the old Roman provinces and urban centres. The interregnum is said to have lasted a decade according to Paul the Deacon, but all other sources—the Fredegarii Chronicon, the Origo Gentis Langobardorum, the Chronicon Gothanum, and the Copenhagen continuator of Prosper Tiro—accord it twelve years. Here is how Paul describes the dukes' rule:

After his death the Langobards had no king for ten years but were under dukes, and each one of the dukes held possession of his own city, Zaban of Ticinum, Wallari of Bergamus, Alichis of Brexia, Euin of Tridentum, Gisulf of Forum Julii. But there were thirty other dukes besides these in their own cities. In these days many of the noble Romans were killed from love of gain, and the remainder were divided among their "guests" and made tributaries, that they should pay the third part of their products to the Langobards. By these dukes of the Langobards in the seventh year from the coming of Alboin and of his whole people, the churches were despoiled, the priests killed, the cities overthrown, the people who had grown up like crops annihilated, and besides those regions which Alboin had taken, the greater part of Italy was seized and subjugated by the Langobards.

Gisulf I was the duke of Benevento from 689, when his brother Grimoald II died. His father was Romuald I. His mother was Theodrada, daughter of Duke Lupus of Friuli, and she exercised the regency for him for the first years of his reign.

Pemmo was the Duke of Friuli for twenty-six years, from about 705 to his death. He was the son of Billo of Belluno.

Marepaphias was a Lombard title of Germanic origin meaning "master of the horse", probably somewhat analogous to the Latin title comes stabuli or constable. According to Grimm, it came from mar or mare meaning "horse" and paizan meaning "to put on the bit".

Ansa was a noblewoman who became the Queen of the Lombards in 756 and reigned until their fall to the Franks in 774 AD. She, like other Medieval Queens at the time, played a significant role in the stability and preservation of the later Lombard Kingdom, particularly through her religious contributions, donations, and political relationships with neighboring Kingdoms. She reigned alongside her husband, King Desiderius, in Northern Italy. She lived her final years exiled to a monastery until her death.

The Kingdom of the Lombards, also known as the Lombard Kingdom and later as the Kingdom of all Italy, was an early medieval state established by the Lombards, a Germanic people, on the Italian Peninsula in the latter part of the 6th century. The king was traditionally elected by the very highest-ranking aristocrats, the dukes, as several attempts to establish a hereditary dynasty failed. The kingdom was subdivided into a varying number of duchies, ruled by semi-autonomous dukes, which were in turn subdivided into gastaldates at the municipal level. The capital of the kingdom and the center of its political life was Pavia in the modern northern Italian region of Lombardy.

Garibald I was Duke of Bavaria from 555 until 591. He was the head of the Agilolfings, and the ancestor of the Bavarian dynasty that ruled the Kingdom of the Lombards.

The Duchy of Friuli was a Lombard duchy in present-day Friuli, the first to be established after the conquest of the Italian peninsula in 568. It was one of the largest domains in Langobardia Major and an important buffer between the Lombard kingdom and the Slavs, Avars, and the Byzantine Empire. The original chief city in the province was Roman Aquileia, but the Lombard capital of Friuli was Forum Julii, modern Cividale.

Wechtar, a Lombard from Vicenza, was the Duke of Friuli from 666 to 678. He took control of Friuli at the command of King Grimoald following the rebellion of Lupus and Arnefrit and the invasion of the Avars. According to Paul the Deacon, he was a mild and fair ruler.

Landolfus Sagax or Landolfo Sagace was a Langobard historian who wrote a Historia Romana in the Beneventan Duchy.

Corvulus was the Duke of Friuli for a brief spell in the early eighth century AD. Virtually nothing is known about his origin and life; he replaced Ferdulf, but he apparently offended King Aripert II and was arrested and had his eyes gouged out. He "lived ignominiously" in shame as an obscure, blind exile thereafter, according to Paul the Deacon. He was ultimately replaced by Pemmo.

Adelperga was a Lombard noblewoman, Duchess of Benevento by marriage to Arechis II of Benevento. She acted as regent of Benevento for her son Grimoald in 787-788. She was the third of four daughters of Desiderius, King of the Lombards, and his wife Ansa. Her elder sister Desiderata was a wife of Charlemagne.

Among the Lombards, the duke or dux was the man who acted as political and military commander of a set of "military families", irrespective of any territorial appropriation.