The cuisine of ancient Rome changed greatly over the duration of the civilization's existence. Dietary habits were affected by the political changes from kingdom to republic to empire, and Roman trading with foreigners along with the empire's enormous expansion exposed Romans to many new foods, provincial culinary habits and cooking methods.

The early history of gardening is largely entangled with the history of agriculture, with gardens that were mainly ornamental generally the preserve of the elite until quite recent times. Smaller gardens generally had being a kitchen garden as their first priority, as is still often the case.

In ancient Greek and Roman architecture, a peristyle is a continuous porch formed by a row of columns surrounding the perimeter of a building or a courtyard. Tetrastoön is a rarely used archaic term for this feature. The peristyle in a Greek temple is a peristasis. In the Christian ecclesiastical architecture that developed from the Roman basilica, a courtyard peristyle and its garden came to be known as a cloister.

The Villa of the Papyri was an ancient Roman villa in Herculaneum, in what is now Ercolano, southern Italy. It is named after its unique library of papyri scrolls, discovered in 1750. The Villa was considered to be one of the most luxurious houses in all of Herculaneum and in the Roman world. Its luxury is shown by its exquisite architecture and by the large number of outstanding works of art discovered, including frescoes, bronzes and marble sculpture which constitute the largest collection of Greek and Roman sculptures ever discovered in a single context.

Nerium oleander, commonly known as oleander or rosebay, is a shrub or small tree cultivated worldwide in temperate and subtropical areas as an ornamental and landscaping plant. It is the only species currently classified in the genus Nerium, belonging to subfamily Apocynoideae of the dogbane family Apocynaceae. It is so widely cultivated that no precise region of origin has been identified, though it is usually associated with the Mediterranean Basin.

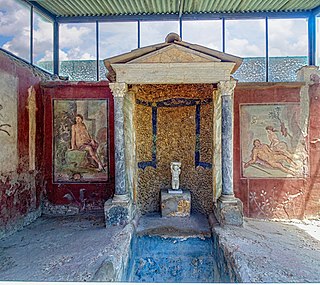

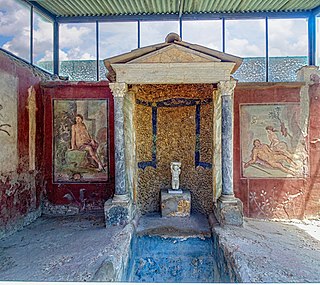

A nymphaeum or nymphaion, in ancient Greece and Rome, was a monument consecrated to the nymphs, especially those of springs.

A distinction is made between Greek gardens, made in ancient Greece, and Hellenistic gardens, made under the influence of Greek culture in late classical times. Little is known about either.

The Getty Villa is an educational center and art museum located at the easterly end of the Malibu coast in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, United States. One of two campuses of the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Villa is dedicated to the study of the arts and cultures of ancient Greece, Rome, and Etruria. The collection has 44,000 Greek, Roman, and Etruscan antiquities dating from 6,500 BC to 400 AD, including the Lansdowne Heracles and the Victorious Youth. The UCLA/Getty Master's Program in Archaeological and Ethnographic Conservation is housed on this campus.

The Villa Poppaea is an ancient luxurious Roman seaside villa located in Torre Annunziata between Naples and Sorrento, in Southern Italy. It is also called the Villa Oplontis or Oplontis Villa A as it was situated in the ancient Roman town of Oplontis.

Wilhelmina Mary Feemster Jashemski was an American scholar of the ancient site of Pompeii, where her archaeological investigations focused on the evidence of gardens and horticulture in the ancient city. She is remembered for her contributions to archaeobotany at Pompeiian sites, as she developed methods for preserving the remains of roots from antiquity, known as root casting.

The House of the Tragic Poet is a Roman house in Pompeii, Italy dating to the 2nd century BCE. The house is famous for its elaborate mosaic floors and frescoes depicting scenes from Greek mythology.

The House of Loreius Tiburtinus is renowned for well-preserved art, mainly in wall-paintings as well as its large gardens.

Villa Boscoreale is a name given to any of several Roman villas discovered in the district of Boscoreale, Italy. They were all buried and preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, along with Pompeii and Herculaneum. The only one visible in situ today is the Villa Regina, the others being reburied soon after their discovery. Although these villas can be classified as "rustic" rather than of otium due to their agricultural sections and sometimes lack of the most luxurious amenities, they were often embellished with extremely luxurious decorations such as frescoes, testifying to the wealth of the owners. Among the most important finds are the exquisite frescoes from the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor and the sumptuous Boscoreale Treasure of the Villa della Pisanella, which is now displayed in several major museums.

Pompeii was a city in what is now the municipality of Pompei, near Naples, in the Campania region of Italy. Along with Herculaneum, Stabiae, and many surrounding villas, the city was buried under 4 to 6 m of volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Stabiae was an ancient city situated near the modern town of Castellammare di Stabia and approximately 4.5 km southwest of Pompeii. Like Pompeii, and being only 16 km (9.9 mi) from Mount Vesuvius, it was largely buried by tephra ash in the 79 AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius, in this case at a shallower depth of up to 5 m.

Herculaneum is an ancient Roman town located in the modern-day comune of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under a massive pyroclastic flow in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

The House of the Centenary was the house of a wealthy resident of Pompeii, preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. The house was discovered in 1879, and was given its modern name to mark the 18th centenary of the disaster. Built in the mid-2nd century BC, it is among the largest houses in the city, with private baths, a nymphaeum, a fish pond (piscina), and two atria. The Centenary underwent a remodeling around 15 AD, at which time the bath complex and swimming pool were added. In the last years before the eruption, several rooms had been extensively redecorated with a number of paintings.

Foodscaping is a modern term for integrating edible plants into ornamental landscapes. It is also referred to as edible landscaping and has been described as a crossbreed between landscaping and farming. As an ideology, foodscaping aims to show that edible plants are not only consumable but can also be appreciated for their aesthetic qualities. Foodscaping spaces are seen as multi-functional landscapes that are visually attractive and also provide edible returns. Foodscaping is a method of providing fresh food affordably and sustainably.

The Pompeii Lakshmi is an ivory statuette that was discovered in the ruins of Pompeii, a Roman city destroyed in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius 79 CE. It was found by Amedeo Maiuri, an Italian scholar, in 1938. The statuette has been dated to the first-century CE. The statuette is thought of as representing an Indian goddess of feminine beauty and fertility. It is possible that the sculpture originally formed the handle of a mirror. The yakshi is evidence of commercial trade between India and Rome in the first century CE.

Several non-native societies had an influence on Ancient Pompeian culture. Historians’ interpretation of artefacts, preserved by the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79, identify that such foreign influences came largely from Greek and Hellenistic cultures of the Eastern Mediterranean, including Egypt. Greek influences were transmitted to Pompeii via the Greek colonies in Magna Graecia, which were formed in the 8th century BC. Hellenistic influences originated from Roman commerce, and later conquest of Egypt from the 2nd century BC.