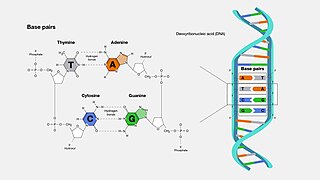

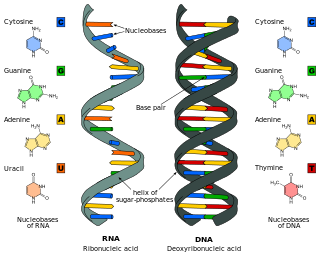

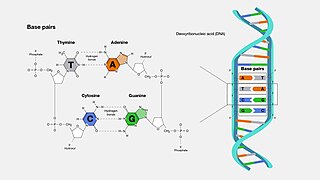

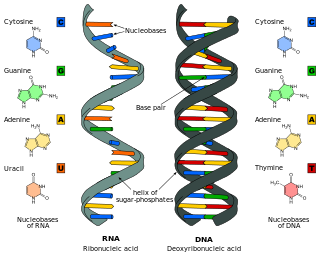

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA and RNA. Dictated by specific hydrogen bonding patterns, "Watson–Crick" base pairs allow the DNA helix to maintain a regular helical structure that is subtly dependent on its nucleotide sequence. The complementary nature of this based-paired structure provides a redundant copy of the genetic information encoded within each strand of DNA. The regular structure and data redundancy provided by the DNA double helix make DNA well suited to the storage of genetic information, while base-pairing between DNA and incoming nucleotides provides the mechanism through which DNA polymerase replicates DNA and RNA polymerase transcribes DNA into RNA. Many DNA-binding proteins can recognize specific base-pairing patterns that identify particular regulatory regions of genes.

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links proteinogenic amino acids in an order specified by messenger RNA (mRNA), using transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules to carry amino acids and to read the mRNA three nucleotides at a time. The genetic code is highly similar among all organisms and can be expressed in a simple table with 64 entries.

Nucleobases are nitrogen-containing biological compounds that form nucleosides, which, in turn, are components of nucleotides, with all of these monomers constituting the basic building blocks of nucleic acids. The ability of nucleobases to form base pairs and to stack one upon another leads directly to long-chain helical structures such as ribonucleic acid (RNA) and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). Five nucleobases—adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), thymine (T), and uracil (U)—are called primary or canonical. They function as the fundamental units of the genetic code, with the bases A, G, C, and T being found in DNA while A, G, C, and U are found in RNA. Thymine and uracil are distinguished by merely the presence or absence of a methyl group on the fifth carbon (C5) of these heterocyclic six-membered rings. In addition, some viruses have aminoadenine (Z) instead of adenine. It differs in having an extra amine group, creating a more stable bond to thymine.

A DNA polymerase is a member of a family of enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of DNA molecules from nucleoside triphosphates, the molecular precursors of DNA. These enzymes are essential for DNA replication and usually work in groups to create two identical DNA duplexes from a single original DNA duplex. During this process, DNA polymerase "reads" the existing DNA strands to create two new strands that match the existing ones. These enzymes catalyze the chemical reaction

DNA primase is an enzyme involved in the replication of DNA and is a type of RNA polymerase. Primase catalyzes the synthesis of a short RNA segment called a primer complementary to a ssDNA template. After this elongation, the RNA piece is removed by a 5' to 3' exonuclease and refilled with DNA.

DNA synthesis is the natural or artificial creation of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) molecules. DNA is a macromolecule made up of nucleotide units, which are linked by covalent bonds and hydrogen bonds, in a repeating structure. DNA synthesis occurs when these nucleotide units are joined to form DNA; this can occur artificially or naturally. Nucleotide units are made up of a nitrogenous base, pentose sugar (deoxyribose) and phosphate group. Each unit is joined when a covalent bond forms between its phosphate group and the pentose sugar of the next nucleotide, forming a sugar-phosphate backbone. DNA is a complementary, double stranded structure as specific base pairing occurs naturally when hydrogen bonds form between the nucleotide bases.

Xenobiology (XB) is a subfield of synthetic biology, the study of synthesizing and manipulating biological devices and systems. The name "xenobiology" derives from the Greek word xenos, which means "stranger, alien". Xenobiology is a form of biology that is not (yet) familiar to science and is not found in nature. In practice, it describes novel biological systems and biochemistries that differ from the canonical DNA–RNA-20 amino acid system. For example, instead of DNA or RNA, XB explores nucleic acid analogues, termed xeno nucleic acid (XNA) as information carriers. It also focuses on an expanded genetic code and the incorporation of non-proteinogenic amino acids, or “xeno amino acids” into proteins.

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA, that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protein-coding genes and non-coding genes.

Steven Albert Benner is an American chemist. He has been a professor at Harvard University, ETH Zurich, and most recently at the University of Florida, where he was the V.T. & Louise Jackson Distinguished Professor of Chemistry. In 2005, he founded The Westheimer Institute of Science and Technology (TWIST) and the Foundation For Applied Molecular Evolution. Benner has also founded the companies EraGen Biosciences and Firebird BioMolecular Sciences LLC.

Missense mRNA is a messenger RNA bearing one or more mutated codons that yield polypeptides with an amino acid sequence different from the wild-type or naturally occurring polypeptide. Missense mRNA molecules are created when template DNA strands or the mRNA strands themselves undergo a missense mutation in which a protein coding sequence is mutated and an altered amino acid sequence is coded for.

Synthetic genomics is a nascent field of synthetic biology that uses aspects of genetic modification on pre-existing life forms, or artificial gene synthesis to create new DNA or entire lifeforms.

Artificial gene synthesis, or simply gene synthesis, refers to a group of methods that are used in synthetic biology to construct and assemble genes from nucleotides de novo. Unlike DNA synthesis in living cells, artificial gene synthesis does not require template DNA, allowing virtually any DNA sequence to be synthesized in the laboratory. It comprises two main steps, the first of which is solid-phase DNA synthesis, sometimes known as DNA printing. This produces oligonucleotide fragments that are generally under 200 base pairs. The second step then involves connecting these oligonucleotide fragments using various DNA assembly methods. Because artificial gene synthesis does not require template DNA, it is theoretically possible to make a completely synthetic DNA molecule with no limits on the nucleotide sequence or size.

Nucleic acid analogues are compounds which are analogous to naturally occurring RNA and DNA, used in medicine and in molecular biology research. Nucleic acids are chains of nucleotides, which are composed of three parts: a phosphate backbone, a pentose sugar, either ribose or deoxyribose, and one of four nucleobases. An analogue may have any of these altered. Typically the analogue nucleobases confer, among other things, different base pairing and base stacking properties. Examples include universal bases, which can pair with all four canonical bases, and phosphate-sugar backbone analogues such as PNA, which affect the properties of the chain . Nucleic acid analogues are also called xeno nucleic acids and represent one of the main pillars of xenobiology, the design of new-to-nature forms of life based on alternative biochemistries.

An expanded genetic code is an artificially modified genetic code in which one or more specific codons have been re-allocated to encode an amino acid that is not among the 22 common naturally-encoded proteinogenic amino acids.

Genetic engineering is the science of manipulating genetic material of an organism. The first artificial genetic modification accomplished using biotechnology was transgenesis, the process of transferring genes from one organism to another, first accomplished by Herbert Boyer and Stanley Cohen in 1973. It was the result of a series of advancements in techniques that allowed the direct modification of the genome. Important advances included the discovery of restriction enzymes and DNA ligases, the ability to design plasmids and technologies like polymerase chain reaction and sequencing. Transformation of the DNA into a host organism was accomplished with the invention of biolistics, Agrobacterium-mediated recombination and microinjection. The first genetically modified animal was a mouse created in 1974 by Rudolf Jaenisch. In 1976 the technology was commercialised, with the advent of genetically modified bacteria that produced somatostatin, followed by insulin in 1978. In 1983 an antibiotic resistant gene was inserted into tobacco, leading to the first genetically engineered plant. Advances followed that allowed scientists to manipulate and add genes to a variety of different organisms and induce a range of different effects. Plants were first commercialized with virus resistant tobacco released in China in 1992. The first genetically modified food was the Flavr Savr tomato marketed in 1994. By 2010, 29 countries had planted commercialized biotech crops. In 2000 a paper published in Science introduced golden rice, the first food developed with increased nutrient value.

Xeno nucleic acids (XNA) are synthetic nucleic acid analogues that have a different backbone from the ribose and deoxyribose found in the nucleic acids of naturally occurring RNA and DNA.

d5SICS is an artificial nucleoside containing 6-methylisoquinoline-1-thione-2-yl group instead of a base.

Floyd E. Romesberg is an American biotechnologist, biochemist, and geneticist formerly at Scripps Research in San Diego, California. He is known for leading the team that created the first Unnatural Base Pair (UBP), thus expanding the genetic alphabet of four letters to six in 2012, the first semi-synthetic organism in 2014, and the first functional semi-synthetic organism that can reproduce its genetic material in successive offspring, in 2017. He left Scripps after a Title IX investigation.

Hachimoji DNA is a synthetic nucleic acid analog that uses four synthetic nucleotides in addition to the four present in the natural nucleic acids, DNA and RNA. This leads to four allowed base pairs: two unnatural base pairs formed by the synthetic nucleobases in addition to the two normal pairs. Hachimoji bases have been demonstrated in both DNA and RNA analogs, using deoxyribose and ribose respectively as the backbone sugar.

Philipp Holliger is a Swiss molecular biologist best known for his work on xeno nucleic acids (XNAs) and RNA engineering. Holliger is a program leader at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology.