This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page . (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

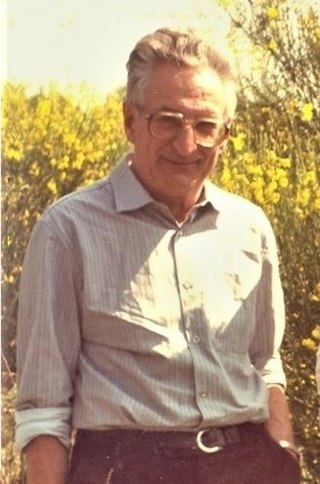

Daniel Elliot Stuntz (March 15, 1909 - March 5, 1983) was an American mycologist.

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page . (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Daniel Elliot Stuntz (March 15, 1909 - March 5, 1983) was an American mycologist.

Stuntz was born in Milford, Ohio, United States. Before he went to college, he studied in Queen Anne High School, Seattle. In autumn 1931, he enrolled at the University of Washington and received his Bachelor of Science degree in 1935. Stuntz began his undergraduate study as a forestry major. After taking a general mycology course offered by J. W. Hotson in the botany department, he developed an interest in fungi. Hence, he decided to change his major to Botany.

After he finished his bachelor's degree study, he began his master's degree with Dr. Hotson while working on Inocybe . (Stuntz and Hotson 1938) He did not finish his master's degree; instead, he went to Yale University for his doctoral degree. His transfer was encouraged by Professor T. C. Frye, who viewed Stuntz as a potential replacement of Dr. Hotson, whose health was becoming problematic. Amazingly, John S. Boyce accepted Stuntz as a student and allowed him continue to do Inocybe research, which is not Dr. Boyce's expertise. Stunz finished his doctoral degree at Yale in 1940.

The earliest record of Stuntz's research activities can be traced back to March 30, 1934, when he was a junior in college. By that time, he began to collect, photograph and describe agarics as well as other fungi. Later, Stuntz was influenced by Dr. Hotson to begin working on the agaric taxonomy. In addition, Alexander H. Smith was another person who had a great impact on Daniel's choice of profession. They met each other on the Olympic Mountains during collections and after that, they began a long friendship. Alex kept encouraging Stuntz to continue his work on Inocybe and other agaric genera, which laid the fundamental basis for Stuntz's taxonomy works in the future. Stuntz kept working on Inocybe during his master's and doctoral degree.

In 1940, after he finished his doctoral degree from Yale, he was hired as an instructor at the University of Washington. He retained this title until 1945 when he was promoted as an assistant professor and, later, in 1950 he became an associate professor. In 1958, he became a professor in the botany department and kept this title until he retired. At the beginning of his professional journey as a fungal taxonomist, he collected almost every agaric he could find. Later, due to teaching commitments, his collection was mainly limited to Pluteus , Hebeloma and Inocybe. Eventually, he spent all his efforts concentrating on Inocybe classification.

During his teaching process, Stuntz would collect almost every group of fungi he could find and try to identify it. He would write his own keys to his collections and a few of them were eventually published. One of his important publications was a book named How to identify mushrooms to Genus IV: keys to families and Genera, published in 1977. (Stuntz 1977) During his last several years, he developed an interest in the resupinate, nonporoid Aphyllophorales and enrolled several students working on those. (Libonati-Barnes 1981) Throughout his professional career, he had served as mentor for 39 graduate students and published 40 papers.

Stuntz has a wide interest in the fungi collection and identification. His personal collection number had over 20,000 specimens. Besides his personal interest and collections, he also developed an excellent fungal herbarium at the University of Washington, in which most of the materials were identified to genus and species. Some of the specimens were exchanged from other sources and this directly led to the wide diversity of fungal group collection of the herbarium though Stuntz was mainly focused on certain group studies.

Stuntz was a talented linguist, which offered him the potentiality to be a bibliophile of the first order. Benefiting from different literature resources such as University of Washington Libraries, Yale University Library, and Michigan mycological library, he deeply understood the importance of an extensive library to researchers, and decided to put both money and time into building a mycological library, which was later called the superb mycological library in the University of Washington. Stuntz purchased all the library items using his own money and many of them were fairly expensive relative to Stuntz's salary. Among the approximately 1300 books in his mycological library were also expensive and rare volumes. After he died, he donated his book collections to both the Department of Botany and Suzzallo Library. According to his intention, these books and papers are available to researchers and others.(Ammirati and Libonati-Barnes 1986)

One of the most noticeable gifts of Stuntz was his teaching ability. He could efficiently deliver the scientific information to a wide variety of people: from the mycological researchers to the amateurs. His lecture was described as well organized, beautifully illustrated, and appropriately-paced. In 1951, His evaluation was ranked fourth among all of the teachers in the University of Washington. In 1974, he received the Alumni Distinguished Teaching Award, which indicated the recognition to him by the public.(Information from winners of UW's distinguished teaching awards)

For years, Stuntz was a 'public servant.' Not only did he help with the identification of fungi, but he also spent considerable amount of time giving lectures to amateur mycologists. One of his major contributions to the amateur mycology is that he and the members of Pacific Northwest mushroom societies established the Pacific Northwest Key Council. In addition, Stuntz's most important tribute to the public service is the establishment of the Daniel Elliot Stuntz Memorial foundation by the amateur and professional mycologists in the Pacific Northwest. This foundation is aimed to provide financial support to students pursuing advanced degree in the fungal systematics and to provide financial support for travel expenses of amateur and professional mycologists in the Pacific Northwest. In the past 7 years, the foundation has contributed over $68,000 in grants to support the mycological studies.(Information from website of Puget Sound Mycological Society)

Stuntz had interest not only in science, but also in arts. He played the piano well and had a great love on classic chamber music. However, Stuntz's father did not think the art is a practical field, so the lack of encouragement from his family may have directly lead him to give up his musical interest. Besides the love of music, Stuntz also loved outdoor recreations such as hiking. In addition, he played badminton for several years and was known as an excellent player.

Mycology is the branch of biology concerned with the study of fungi, including their taxonomy, genetics, biochemical properties, and use by humans. Fungi can be a source of tinder, food, traditional medicine, as well as entheogens, poison, and infection. Yeasts are among the most heavily utilized members of the Kingdom Fungi, particularly in food manufacturing.

Edred John Henry Corner FRS was an English mycologist and botanist who occupied the posts of assistant director at the Singapore Botanic Gardens (1929–1946) and Professor of Tropical Botany at the University of Cambridge (1965–1973). Corner was a Fellow of Sidney Sussex College from 1959.

Inocybe is a large genus of mushroom-forming fungi with over 1400 species, including all forms and varieties. Members of Inocybe are mycorrhizal, and some evidence shows that the high degree of speciation in the genus is due to adaptation to different trees and perhaps even local environments.

Christopher Edmund Broome was a British mycologist. The standard author abbreviation Broome is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.

Narcisse Théophile Patouillard was a French pharmacist and mycologist.

Alexander Hanchett Smith was an American mycologist known for his extensive contributions to the taxonomy and phylogeny of the higher fungi, especially the agarics.

Squamanita is a genus of parasitic fungi in the family Squamanitaceae. Basidiocarps superficially resemble normal agarics but emerge from parasitized fruit bodies of deformed host agarics.

Richard William George Dennis, PhD, was an English mycologist and plant pathologist.

Derek Agutter Reid was an English mycologist.

Arthur Anselm Pearson was an English mycologist. He often published under the name A. A. Pearson. The standard author abbreviation A.Pearson is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.

Gertrude Simmons Burlingham was an early 20th-century mycologist best known for her work on American Russula and Lactarius and pioneering the use of microscopic spore features and iodine staining for species identification.

Meinhard Michael Moser was an Austrian mycologist. His work principally concerned the taxonomy, chemistry, and toxicity of the gilled mushrooms (Agaricales), especially those of the genus Cortinarius, and the ecology of ectomycorrhizal relationships. His contributions to the Kleine Kryptogamenflora von Mitteleuropa series of mycological guidebooks were well regarded and widely used. In particular, his 1953 Blätter- und Bauchpilze [The Gilled and Gasteroid Fungi ], which became known as simply "Moser", saw several editions in both the original German and in translation. Other important works included a 1960 monograph on the genus Phlegmacium and a 1975 study of members of Cortinarius, Dermocybe, and Stephanopus in South America, co-authored with the mycologist Egon Horak.

Robert Lee Gilbertson was a distinguished American mycologist and educator. He was a faculty member at University of Arizona for 26 years until his retirement from teaching in 1995; he was a Professor Emeritus at U of A until his death on October 26, 2011, in Tucson, Arizona. 2011. He held concurrent positions as Plant Pathologist, Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Arizona (1967–95) for a project Research on wood-rotting fungi and other fungi associated with southwestern plants and was collaborator and consultant with Center for Forest Mycology Research, US Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wisconsin (1957–1981).

James Martin Trappe is a mycologist and expert in the field of North American truffle species. He has authored or co-authored 450 scientific papers and written three books on the subject. MycoBank lists him as either author or co-author of 401 individual species, and over the course of his career he has helped guide research on mycorrhizal fungi, and reshaped truffle taxonomy: establishing a new order, two new families, and 40 individual genera.

Lois Hattery Tiffany (1924–2009) was a mycologist who taught for over 50 years at Iowa State University (ISU) and was known as "Iowa's mushroom lady". She won a number of awards, including becoming the first recipient of both the Mycological Society of America's Weston Award and the Iowa Governor’s Medal for Science Teaching. She published on many different aspects of fungal life, but her special area of research was Iowa's prairie fungi.

David Norman Pegler is a British mycologist. Until his retirement in 1998, he served as the Head of Mycology and assistant keeper of the herbarium at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew. Pegler received his BSc from London University in 1960, thereafter studying tropical Agaricales with R.W.G. Dennis as his graduate supervisor. He earned a master's degree in 1966, and a PhD in 1974. His graduate thesis was on agarics of east Africa, later published as A preliminary agaric flora of East Africa in 1977. In 1989, London University awarded him a DSc for his research into the Agaricales.

Kenneth A. Harrison was a Canadian mycologist. He was for many years a plant pathologist at what is now the Atlantic Food and Horticulture Research Centre in Nova Scotia. After retirement, he contributed to the taxonomy of the Agaricomycotina, particularly the tooth fungi of the families Hydnaceae and Bankeraceae, in which he described several new species.

Robert W. Lichtwardt was a Brazilian-born American mycologist specializing in the study of arthropod-associated, gut-dwelling fungi (trichomycetes). He is known for his online monograph and interactive keys to trichomycete taxa.

Stanley John Hughes (1918–2019) was a Canadian scientist who is known throughout the global field of mycology for developing and introducing a precise and meticulous system for classifying fungi that is still used today. A naturalized Canadian, he was a federal research scientist for Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada at what is today the Ottawa Research and Development Centre.

John William Hotson was an American botanist and a professor of botany at University of Washington. He was a founder of the herbarium at the University of Washington and a pioneer of the systematic study of bulbiliferous anamorphic fungi. He was the first to make a comprehensive study of plant rust in the state of Washington.