Related Research Articles

Post-capitalism is in part a hypothetical state in which the economic systems of the world can no longer be described as forms of capitalism. Various individuals and political ideologies have speculated on what would define such a world. According to classical Marxist and social evolutionary theories, post-capitalist societies may come about as a result of spontaneous evolution as capitalism becomes obsolete. Others propose models to intentionally replace capitalism, most notably socialism, communism, anarchism, nationalism and degrowth.

An online marketplace is a type of e-commerce website where product or service information is provided by multiple third parties. Online marketplaces are the primary type of multichannel ecommerce and can be a way to streamline the production process.

Open data are data that are openly accessible, exploitable, editable and shareable by anyone for any purpose. Open data are generally licensed under an open license.

Shoshana Zuboff is an American author, professor, social psychologist, philosopher, and scholar.

PublicAffairs is a book publishing company located in New York City and has been a part of the Hachette Book Group since 2016.

Urban informatics refers to the study of people creates , applying and using information and communication technology and data in the context of cities and urban environments. It sits at the conjunction of urban science, geomatics, and informatics, with an ultimate goal of creating more smart and sustainable cities. Various definitions are available, some provided in the Definitions section.

Cross-device tracking is technology that enables the tracking of users across multiple devices such as smartphones, television sets, smart TVs, and personal computers.

Data activism is a social practice that uses technology and data. It emerged from existing activism sub-cultures such as hacker an open-source movements. Data activism is a specific type of activism which is enabled and constrained by the data infrastructure. It can use the production and collection of digital, volunteered, open data to challenge existing power relations. It is a form of media activism; however, this is not to be confused with slacktivism. It uses digital technology and data politically and proactively to foster social change. Forms of data activism can include digital humanitarianism and engaging in hackathons. Data activism is a social practice that is becoming more well known with the expansion of technology, open-sourced software and the ability to communicate beyond an individual's immediate community. The culture of data activism emerged from previous forms of media activism, such as hacker movements. A defining characteristic of data activism is that ordinary citizens can participate, in comparison to previous forms of media activism where elite skill sets were required to participate. By increasingly involving average users, they are a signal of a change in perspective and attitude towards massive data collection emerging within the civil society realm.

Data exhaust or exhaust data is the trail of data left by the activities of an Internet or other computer system users during their online activity, behavior, and transactions. This is part of a broader category of unconventional data that includes geospatial, network, and time-series data and may be useful for predictive analytics. Every visited website, clicked link, and even hovering with a mouse is collected, leaving behind a trail of data. An enormous amount of often raw data are created, which can be in the form of cookies, temporary files, logfiles, storable choices, and more. This information can help to improve the online experience, for example through customized content. It can be used to improve tracking trends and studying data exhaust also improves the user interface and the layout design. On the other hand, they can also compromise privacy, as they offer a valuable insight into the user's habits. For example, as the world's most popular website, Google, uses this data exhaust to refine the predictive value of their products.

Surveillance capitalism is a concept in political economics which denotes the widespread collection and commodification of personal data by corporations. This phenomenon is distinct from government surveillance, although the two can be mutually reinforcing. The concept of surveillance capitalism, as described by Shoshana Zuboff, is driven by a profit-making incentive, and arose as advertising companies, led by Google's AdWords, saw the possibilities of using personal data to target consumers more precisely.

Big data ethics, also known simply as data ethics, refers to systemizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong conduct in relation to data, in particular personal data. Since the dawn of the Internet the sheer quantity and quality of data has dramatically increased and is continuing to do so exponentially. Big data describes this large amount of data that is so voluminous and complex that traditional data processing application software is inadequate to deal with them. Recent innovations in medical research and healthcare, such as high-throughput genome sequencing, high-resolution imaging, electronic medical patient records and a plethora of internet-connected health devices have triggered a data deluge that will reach the exabyte range in the near future. Data ethics is of increasing relevance as the quantity of data increases because of the scale of the impact.

Data shadows refer to the information that a person leaves behind unintentionally while taking part in daily activities such as checking their e-mails, scrolling through social media or even by using their debit or credit card.

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power is a 2019 non-fiction book by Shoshana Zuboff which looks at the development of digital companies like Google and Amazon, and suggests that their business models represent a new form of capitalist accumulation that she calls "surveillance capitalism".

Platform capitalism is an economic and business model in which digital platforms play a central role in facilitating interactions, transactions, and services between different user groups, typically consumers and producers. This model of capitalism has emerged and expanded with the rise of the Internet and digital technologies, transforming various sectors of the economy from retail and transportation to media and labor markets. Four main facets of platform capitalism are: crowdsourcing, sharing economy, gig economy and platform economy. Key characteristics of platform capitalism include:

Ethics of quantification is the study of the ethical issues associated to different forms of visible or invisible forms of quantification. These could include algorithms, metrics/indicators, statistical and mathematical modelling, as noted in a review of various aspects of sociology of quantification.

A digital platform is a software-based online infrastructure that facilitates user interactions and transactions.

Data imaginaries are a form of cultural imaginary related to social conceptions of data, a concept that comes from the field of critical data studies. A data imaginary is a particular framing of data that defines what data are and what can be done with them. Imaginaries are produced by social institutions and practices and they influence how people understand and use the object of the imaginary, in this case data.

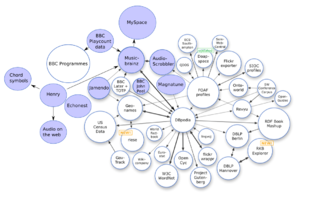

A data ecosystem is the complex environment of co-dependent networks and actors that contribute to data collection, transfer and use. It can span multiple sectors – such as healthcare or finance, to inform one another's practices. A data ecosystem often consists of numerous data assemblages. Research into data ecosystems has developed in response to the rapid proliferation and availability of information through the web, which has contributed to the commodification of data.

Data universalism is an epistemological framework that assumes a single universal narrative of any dataset without any consideration of geographical borders and social contexts. This assumption is enabled by a generalized approach in data collection. Data are used in universal endeavours across social, political, and physical sciences unrestricted from their local source and people. Data are gathered and transformed into a mutual understanding of knowing the world which forms theories of knowledge. One of many fields of critical data studies explores the geologies and histories of data by investigating data assemblages and tracing data lineage which unfolds data histories and geographies (p. 35). This reveals intersections of data politics, praxes, and powers at play which challenges data universalism as a misguided concept.

Benedetta Brevini is an Italian academic, author, journalist, and media and technology reformer. Brevini is currently an associate professor of political economy of communication at The University of Sydney and a Senior Visiting Fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

References

- ↑ Leonelli, Sabrina (5 October 2015). "The Politics of Data:The rising prominence of a data-centric approach to scientific research". The London School of Economics and Political Science.

- ↑ Crawford, Kate (2014). "Critiquing Big Data: Politics, Ethics, Epistemology". International Journal of Communication. 8: 1663–1672.

- ↑ Zuboff, Shoshana (2015). "Big Other: surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization". Journal of Information Technology. 30: 75–89. doi: 10.1057/jit.2015.5 . S2CID 15329793. SSRN 2594754.

- ↑ Srnicek, Nick (2017). Platform Capitalism. Polity.

- ↑ Srnicek, Nick (2017). Platform Capitalism. Polity. p. 99.

- ↑ Chander, Anupam (May 16, 2012). "Facebookistan". North Carolina Law Review. 90 (295). Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ↑ Zuboff, Shoshana (2015). "Big Other: Surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization". Journal of Information Technology. 30: 75–89. doi: 10.1057/jit.2015.5 . S2CID 15329793. SSRN 2594754.

- ↑ Kitchin, Rob (2014). The data revolution. Sage.

- ↑ Gurstein, M (2013-02-03). "Should "open government data" be a product or service (and why does it matter?)". Gurstein's community informatics. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ↑ Simone Noveck, Beth (2011-04-07). "What's in a Name? Open Gov and Good Gov". Huffington Post. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ Kitchin, Rob (2014). The Data Revolution. Sage. p. 52.

- ↑ "About OGP". Open Government Partnership. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ "Methodology". Global Open Data Index. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ Milan, Stefania (2016). "The alternative epistemologies of data activism". Digital Culture & Society. 2 (2): 2. doi:10.14361/dcs-2016-0205. S2CID 152166960. SSRN 2850470.

- ↑ Milan, Stefania (2016). "The alternative epistemologies of data activism". Digital Culture & Society. 2 (2): 2, 3. doi:10.14361/dcs-2016-0205. S2CID 152166960. SSRN 2850470.

- ↑ Milan, Stefania (2016). "The alternative epistemologies of data activism". Digital Culture & Society. 2 (2): 6, 7. doi:10.14361/dcs-2016-0205. S2CID 152166960. SSRN 2850470.

- ↑ Lauriault, Tracey. "datalibre.ca". Data Libre. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ↑ Kannengießer, Sigrid (December 2020). "Reflecting and acting on datafication – CryptoParties as an example of re-active data activism". Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies. 26 (5–6): 1060–1073. doi: 10.1177/1354856519893357 . ISSN 1354-8565.