Pottery, due to its relative durability, comprises a large part of the archaeological record of ancient Greece, and since there is so much of it, it has exerted a disproportionately large influence on our understanding of Greek society. The shards of pots discarded or buried in the 1st millennium BC are still the best guide available to understand the customary life and mind of the ancient Greeks. There were several vessels produced locally for everyday and kitchen use, yet finer pottery from regions such as Attica was imported by other civilizations throughout the Mediterranean, such as the Etruscans in Italy. There were a multitude of specific regional varieties, such as the South Italian ancient Greek pottery.

Exekias was an ancient Greek vase painter and potter who was active in Athens between roughly 545 BC and 530 BC. Exekias worked mainly in the black-figure technique, which involved the painting of scenes using a clay slip that fired to black, with details created through incision. Exekias is regarded by art historians as an artistic visionary whose masterful use of incision and psychologically sensitive compositions mark him as one of the greatest of all Attic vase painters. The Andokides painter and the Lysippides Painter are thought to have been students of Exekias.

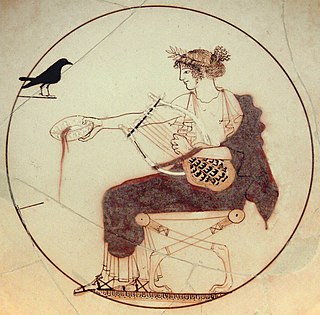

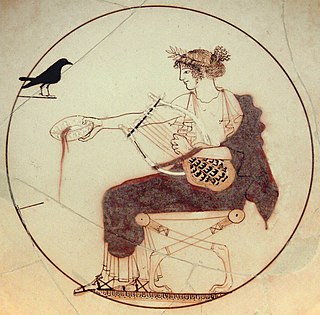

Red-figure pottery is a style of ancient Greek pottery in which the background of the pottery is painted black while the figures and details are left in the natural red or orange color of the clay.

A krater or crater was a large two-handled type of vase in Ancient Greek pottery and metalwork, mostly used for the mixing of wine with water.

A lekythos is a type of ancient Greek vessel used for storing oil, especially olive oil. It has a narrow body and one handle attached to the neck of the vessel, and is thus a narrow type of jug, with no pouring lip; the oinochoe is more like a modern jug. In the "shoulder" and "cylindrical" types which became the most common, especially the latter, the sides of the body are usually vertical by the shoulder, and there is then a sharp change of direction as the neck curves in; the base and lip are normally prominent and flared. However, there are a number of varieties, and the word seems to have been used even more widely in ancient times than by modern archeologists. They are normally in pottery, but there are also carved stone examples.

White-ground technique is a style of white ancient Greek pottery and the painting in which figures appear on a white background. It developed in the region of Attica, dated to about 500 BC. It was especially associated with vases made for ritual and funerary use, if only because the painted surface was more fragile than in the other main techniques of black-figure and red-figure vase painting. Nevertheless, a wide range of subjects are depicted.

Geometric art is a phase of Greek art, characterized largely by geometric motifs in vase painting, that flourished towards the end of the Greek Dark Ages and a little later, c. 1050–700 BC. Its center was in Athens, and from there the style spread among the trading cities of the Aegean. The so-called Greek Dark Ages were considered to last from c. 1100 to 800 BC and include the phases from the Protogeometric period to the Middle Geometric I period, which Knodell (2021) calls Prehistoric Iron Age. The vases had various uses or purposes within Greek society, including, but not limited to, funerary vases and symposium vases.

The pottery of ancient Greece has a long history and the form of Greek vase shapes has had a continuous evolution from Minoan pottery down to the Hellenistic period. As Gisela Richter puts it, the forms of these vases find their "happiest expression" in the 5th and 6th centuries BC, yet it has been possible to date vases thanks to the variation in a form’s shape over time, a fact particularly useful when dating unpainted or plain black-gloss ware.

Etruscan art was produced by the Etruscan civilization in central Italy between the 10th and 1st centuries BC. From around 750 BC it was heavily influenced by Greek art, which was imported by the Etruscans, but always retained distinct characteristics. Particularly strong in this tradition were figurative sculpture in terracotta, wall-painting and metalworking especially in bronze. Jewellery and engraved gems of high quality were produced.

The Archaeological Museum of Nafplio is a museum in the town of Nafplio of the Argolis region in Greece. It has exhibits of the Neolithic, Chalcolithic, Helladic, Mycenaean, Classical, Hellenistic and Roman periods from all over southern Argolis. The museum is situated in the central square of Nafplion. It is housed in two floors of the old Venetian barracks.

Funerary art is any work of art forming, or placed in, a repository for the remains of the dead. The term encompasses a wide variety of forms, including cenotaphs, tomb-like monuments which do not contain human remains, and communal memorials to the dead, such as war memorials, which may or may not contain remains, and a range of prehistoric megalithic constructs. Funerary art may serve many cultural functions. It can play a role in burial rites, serve as an article for use by the dead in the afterlife, and celebrate the life and accomplishments of the dead, whether as part of kinship-centred practices of ancestor veneration or as a publicly directed dynastic display. It can also function as a reminder of the mortality of humankind, as an expression of cultural values and roles, and help to propitiate the spirits of the dead, maintaining their benevolence and preventing their unwelcome intrusion into the lives of the living.

Ancient Greek funerary practices are attested widely in literature, the archaeological record, and in ancient Greek art. Finds associated with burials are an important source for ancient Greek culture, though Greek funerals are not as well documented as those of the ancient Romans.

The Archaeological Museum of Chora is a museum in Chora, Messenia, in southern Greece, whose collections focus on the Mycenaean civilization, particularly from the excavations at the Palace of Nestor and other regions of Messenia. The museum was founded in 1969 by the Greek Archaeological Service under the auspices of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Olympia. At the time, the latter included in its jurisdiction the larger part of Messenia.

There were a number of grave stelai or stelae found among the six shaft graves at Grave Circle A in the site of Mycenae. These stelai mark the burial sites of the Mycenaean dead, much like modern headstones. At least 21 stelai have been discovered from Grave Circle A, with 12 having identifiable relief sculpture. Most were upright, rectangular slabs of oolithic limestone, ranging in date from 1600 to 1500 BCE. The iconography depicted on these stelai include chariot scenes, hunting scenes, and circular and spiral designs characteristic of the Greek Mycenaean Period. Scholars argue that these scenes demonstrate the prevalence of warfare in Mycenaean culture, in addition to signifying a socially stratified society.

Dipylon Kraters are Geometric period Greek terracotta funerary vases found at the Dipylon cemetery; near the Dipylon Gate, in Kerameikos. Kerameikos is known as the ancient potters quarter on the northwest side of the ancient city of Athens and translates to "the city of clay." A krater is a large Ancient Greek painted vase used to mix wine and water, but the large kraters at the Dipylon cemetery served as grave markers.

The Thanatos Painter was an Athenian Ancient Greek vase painter who painted scenes of death on white-ground cylindrical lekythoi. All of the Thanatos Painter's found lekythoi have scenes of or related to death on them, including the eponymous god of death Thanatos carrying away dead bodies.

A pelike was a ceramic container that the Greeks used as storage/transportation for wine and olive oil. As seen in the picture on the right, it had a large belly with thin, open handles. Unlike other transportation jars, a pelike would have a flattened bottom so that it could stand on its own. Pelikes often had one large scene across the belly of the jar with minimal distractions around. This would focus the viewers eyes to the center of the pelike which was often a mythological scene of sorts.

Ancient Greek funerary vases are decorative grave markers made in ancient Greece that were designed to resemble liquid-holding vessels. These decorated vases were placed on grave sites as a mark of elite status. There are many types of funerary vases, such as amphorae, kraters, oinochoe, and kylix cups, among others. One famous example is the Dipylon amphora. Every-day vases were often not painted, but wealthy Greeks could afford luxuriously painted ones. Funerary vases on male graves might have themes of military prowess, or athletics. However, allusions to death in Greek tragedies was a popular motif. Famous centers of vase styles include Corinth, Lakonia, Ionia, South Italy, and Athens.

The Dipylon Amphora is a large Ancient Greek painted vase, made around 760–750 BC, and is now held by the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Discovered at the Dipylon cemetery, this stylistic vessel belonging to the Geometric period is credited to an unknown artist: the Dipylon Master. The amphora is covered entirely in ornamental and geometric patterns, as well as human figures and animal-filled motifs. It is also structurally precise, being that it is as tall as it is wide. These decorations use up every inch of space, and are painted on using the black-figure technique to create the silhouetted shapes. Inspiration for the Greek vase derived not only from its intended purpose as a funerary vessel, but also from artistic remnants of Mycenaean civilization prior to its collapse around 1100 BC. The Dipylon Amphora signifies the passing of an aristocratic woman, who is illustrated along with the procession of her funeral consisting of mourning family and friends situated along the belly of the vase. The woman's nobility and status is further emphasized by the plethora of detail and characterized animals, all which remain in bands circling the neck and belly of the amphora.

The Eleusis Amphora is an ancient Greek neck amphora, now in the Archaeological Museum of Eleusis, that dates back to the Middle Protoattic. The painter of the Eleusis Amphora is known as the Polyphemos Painter. It is decorated with black and white painted figures on a light colored background, which is characteristic of the "Black and White" style commonly seen in Middle Protoattic pottery. The amphora's decoration reflects the pottery of the Orientalizing period, a style in which human and animal figures depict mythological scenes.