Lycia was a historical region in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean Sea in what is today the provinces of Antalya and Muğla in Turkey as well some inland parts of Burdur Province. The region was known to history from the Late Bronze Age records of ancient Egypt and the Hittite Empire.

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus or Tomb of Mausolus was a tomb built between 353 and 350 BC in Halicarnassus for Mausolus, an Anatolian from Caria and a satrap in the Achaemenid Persian Empire, and his sister-wife Artemisia II of Caria. The structure was designed by the Greek architects Satyros and Pythius of Priene. Its elevated tomb structure is derived from the tombs of neighbouring Lycia, a territory Mausolus had invaded and annexed c. 360 BC, such as the Nereid Monument.

Xanthos or Xanthus, also referred to by scholars as Arna, its Lycian name, was an ancient city near the present-day village of Kınık, in Antalya Province, Turkey. The ruins are located on a hill on the left bank of the River Xanthos. The number and quality of the surviving tombs at Xanthos are a notable feature of the site, which, together with nearby Letoon, was declared to be a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1988.

A chaitya, chaitya hall, chaitya-griha, refers to a shrine, sanctuary, temple or prayer hall in Indian religions. The term is most common in Buddhism, where it refers to a space with a stupa and a rounded apse at the end opposite the entrance, and a high roof with a rounded profile. Strictly speaking, the chaitya is the stupa itself, and the Indian buildings are chaitya halls, but this distinction is often not observed. Outside India, the term is used by Buddhists for local styles of small stupa-like monuments in Nepal, Cambodia, Indonesia and elsewhere. In Thailand a stupa, not a stupa hall, is called a chedi. In the historical texts of Jainism and Hinduism, including those relating to architecture, chaitya refers to a temple, sanctuary or any sacred monument.

The Trirashmi Caves, or Nashik Caves, are a group of 23 caves carved between the 1st century BCE and the 3rd century CE, though additional sculptures were added up to about the 6th century, reflecting changes in Buddhist devotional practices. The Buddhist sculptures are a significant group of early examples of Indian rock-cut architecture initially representing the Early Buddhist schools tradition.

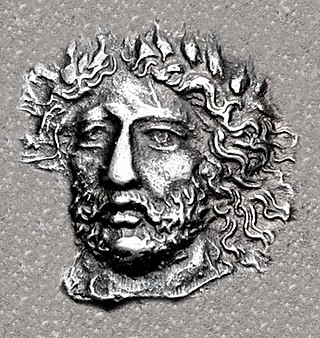

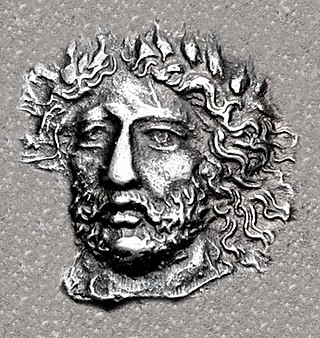

Antiphellus or Antiphellos, known originally as Habesos, was an ancient coastal city in Lycia. The earliest occurrence of its Greek name is on a 4th-century-BCE inscription. Initially settled by the Lycians, the city was occupied by the Persians during the 6th century BCE. It rose in importance under the Greeks, when it served as the port of the nearby inland city of Phellus, but once Phellus started to decline in importance, Antiphellus became the region's largest city, with the ability to mint its own coins. During the Roman period, Antiphellus received funds from the civic benefactor Opramoas of Rhodiapolis that may have been used to help rebuild the city following the earthquake that devastated the region in 141.

Phellus is the site of an ancient Lycian city, situated in a mountainous area near Çukurbağ in Antalya Province,Turkey. The city was mentioned by the Greek geographer and philosopher Strabo in his Geographica. Antiphellus served as the city's port.

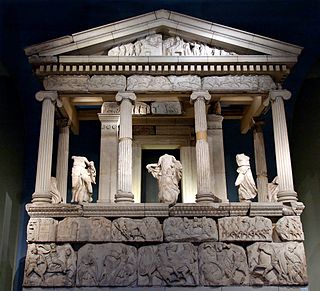

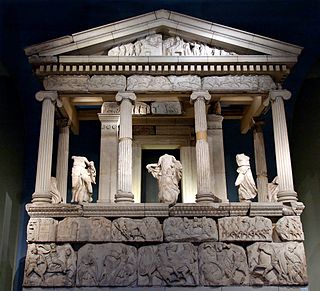

The Nereid Monument is a sculptured tomb from Xanthos in Lycia, close to present-day Fethiye in Mugla Province, Turkey. It took the form of a Greek temple on top of a base decorated with sculpted friezes, and is thought to have been built in the early fourth century BC as a tomb for Arbinas, the Xanthian dynast who ruled western Lycia under the Achaemenid Empire.

The Tomb of Payava is a Lycian tall rectangular free-standing barrel-vaulted stone sarcophagus, and one of the most famous tombs of Xanthos. It was built in the Achaemenid Persian Empire, for Payava, who was probably the ruler of Xanthos, Lycia at the time, in around 360 BC. The tomb was discovered in 1838 and brought to England in 1844 by the explorer Sir Charles Fellows. He described it as a 'Gothic-formed Horse Tomb'. According to Melanie Michailidis, though bearing a "Greek appearance", the Tomb of Payava, the Harpy Tomb and the Nereid Monument were built according to the main Zoroastrian criteria "by being composed of thick stone, raised on plinths off the ground, and having single windowless chambers".

The Harpy Tomb is a marble chamber from a pillar tomb that stands in the abandoned city of Xanthos, capital of ancient Lycia, a region of southwestern Anatolia in what is now Turkey. Built in the Persian Achaemenid Empire, and dating to approximately 480–470 BC, the chamber topped a tall pillar and was decorated with marble panels carved in bas-relief. The tomb was built for an Iranian prince or governor of Xanthus, perhaps Kybernis.

The Xanthian Obelisk, also known as the Xanthos or Xanthus Stele, the Xanthos or Xanthus Bilingual, the Inscribed Pillar of Xanthos or Xanthus, the Harpagus Stele, the Pillar of Kherei and the Columna Xanthiaca, is a stele bearing an inscription currently believed to be trilingual, found on the acropolis of the ancient Lycian city of Xanthos, or Xanthus, near the modern town of Kınık in southern Turkey. It was created when Lycia was part of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, and dates in all likelihood to c. 400 BC. The pillar is seemingly a funerary marker of a dynastic satrap of Achaemenid Lycia. The dynast in question is mentioned on the stele, but his name had been mostly defaced in the several places where he is mentioned: he could be Kherei (Xerei) or more probably his predecessor Kheriga.

Around 535 BCE, the Persian king Cyrus the Great initiated a protracted campaign to absorb parts of India into his nascent Achaemenid Empire. In this initial incursion, the Persian army annexed a large region to the west of the Indus River, consolidating the early eastern borders of their new realm. With a brief pause after Cyrus' death around 530 BCE, the campaign continued under Darius the Great, who began to re-conquer former provinces and further expand the Achaemenid Empire's political boundaries. Around 518 BCE, the Persian army pushed further into India to initiate a second period of conquest by annexing regions up to the Jhelum River in what is today known as Punjab. At peak, the Persians managed to take control of most of modern-day Pakistan and incorporate it into their territory.

Hellenistic influence on Indian art and architecture reflects the artistic and architectural influence of the Greeks on Indian art following the conquests of Alexander the Great, from the end of the 4th century BCE to the first centuries of the common era. The Greeks in effect maintained a political presence at the doorstep, and sometimes within India, down to the 1st century CE with the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom and the Indo-Greek Kingdoms, with many noticeable influences on the arts of the Maurya Empire especially. Hellenistic influence on Indian art was also felt for several more centuries during the period of Greco-Buddhist art.

The theme of death within ancient Greek art has continued from the Early Bronze Age all the way through to the Hellenistic period. The Greeks used architecture, pottery, and funerary objects as different mediums through which to portray death. These depictions include mythical deaths, deaths of historical figures, and commemorations of those who died in war. This page includes various examples of the different types of mediums in which death is presented in Greek art.

The Lycian sarcophagus of Sidon is a sarcophagus discovered in the Royal necropolis of Ayaa near Sidon, Lebanon. It is made of Parian marble, and resembles the shapes of ogival Lycian tombs, such as the Tomb of Payava, hence its name. It is now located in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum. It is dated to circa 430–420 BC. This sarcophagus, as well as others in the Sidon necropolis, belonged to a succession of kings who ruled in the area of Phoenicia between the mid-5th century BC to the end of the 4th century BC.

Arbinas, also Erbinas, Erbbina, was a Lycian Dynast who ruled circa 430/20-400 BCE. He is most famous for his tomb, the Nereid Monument, now on display in the British Museum. Coinage seems to indicate that he ruled in the western part of Lycia, around Telmessos, while his tomb was established in Xanthos. He was a subject of the Achaemenid Empire.

Kybernis or Kubernis, also abbreviated KUB on his coins in Lycian, called Cyberniscus son of Sicas by Herodotus, was a dynast of Lycia, at the beginning of the time it was under the domination of the Achaemenid Empire. He is best known through his tomb, the Harpy Tomb, the decorative remains of which are now in the British Museum. According to Melanie Michailidis, though bearing a "Greek appearance", the Harpy Tomb, the Nereid Monument and the Tomb of Payava were built according main Zoroastrian criteria "by being composed of thick stone, raised on plinths off the ground, and having single windowless chambers".

Perikles, was the last known independent dynast of Lycia. A dynast of Limyra in eastern Lycia c. 375–362 BCE, he eventually ruled the entire country during the Revolt of the Satraps, in defiance of the Achaemenid Empire.

Kheriga was a Dynast of Lycia, who ruled circa 450-410 BCE. Kheriga is mentioned on the succession list of the Xanthian Obelisk, and is probably the owner of the sarcophagus that was standing on top of it.

Kuprlli was a dynast of Lycia, at a time when this part of Anatolia was subject to the Persian, or Achaemenid, Empire. Kuprlli ruled at the time of the Athenian alliance, the Delian League.