Alexios III Angelos, Latinized as Alexius III Angelus, was Byzantine Emperor from March 1195 to 17/18 July 1203. He reigned under the name Alexios Komnenos associating himself with the Komnenos dynasty.

Alexios V Doukas, Latinized as Alexius V Ducas, was Byzantine emperor from February to April 1204, just prior to the sack of Constantinople by the participants of the Fourth Crusade. His family name was Doukas, but he was also known by the nickname Mourtzouphlos or Murtzuphlus (Μούρτζουφλος), referring to either bushy, overhanging eyebrows or a sullen, gloomy character. He achieved power through a palace coup, killing his predecessors in the process. Though he made vigorous attempts to defend Constantinople from the crusader army, his military efforts proved ineffective. His actions won the support of the mass of the populace, but he alienated the elite of the city. Following the fall, sack, and occupation of the city, Alexios V was blinded by his father-in-law, the ex-emperor Alexios III, and later executed by the new Latin regime. He was the last Byzantine emperor to rule in Constantinople until the Byzantine recapture of Constantinople in 1261.

Pope Innocent III, born Lotario dei Conti di Segni, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 until his death on 16 July 1216.

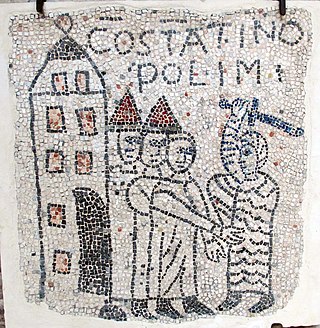

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid Sultanate. However, a sequence of economic and political events culminated in the Crusader army's 1202 siege of Zara and the 1204 sack of Constantinople, rather than the conquest of Egypt as originally planned. This led to the Partitio terrarum imperii Romaniae or the partition of the Byzantine Empire by the Crusaders and their Venetian allies leading to a period known as Frankokratia, or "Rule of the Franks" in Greek.

The Latin Empire, also referred to as the Latin Empire of Constantinople, was a feudal Crusader state founded by the leaders of the Fourth Crusade on lands captured from the Byzantine Empire. The Latin Empire was intended to replace the Byzantine Empire as the Western-recognized Roman Empire in the east, with a Catholic emperor enthroned in place of the Eastern Orthodox Roman emperors. The main objective of the Latin Empire was planned by Venice, which promoted the creation of this state for their self-benefit.

Alexios IV Angelos, Latinized as Alexius IV Angelus, was Byzantine Emperor from August 1203 to January 1204. He was the son of Emperor Isaac II Angelos and his first wife, an unknown Palaiologina, who became a nun with the name Irene. His paternal uncle was his predecessor Emperor Alexios III Angelos. He is widely regarded as one of the worst Byzantine emperors for calling upon the Fourth Crusade to help him gain power, which ultimately led to the sack of Constantinople.

Boniface I, usually known as Boniface of Montferrat, was the ninth Marquis of Montferrat, a leader of the Fourth Crusade (1201–04) and the king of Thessalonica.

Geoffrey of Villehardouin was a French knight and historian who participated in and chronicled the Fourth Crusade. He is considered one of the most important historians of the time period, best known for writing the eyewitness account De la Conquête de Constantinople, about the battle for Constantinople between the Christians of the West and the Christians of the East on 13 April 1204. The Conquest is the earliest French historical prose narrative that has survived to modern times. Ηis full title was: "Geoffroi of Villehardouin, Marshal of Champagne and of Romania".

The Kingdom of Thessalonica was a short-lived Crusader State founded after the Fourth Crusade over conquered Byzantine lands in Macedonia and Thessaly.

Marco Sanudo was the creator and first Duke of the Duchy of the Archipelago, in Italian: "Duca del Mare Egeo e Re di Candia", Barone delle Isole di Nasso, Pario, Milo, Marine ed Andri, duchy granted by the Republic of Venice to him and all his descendants, after the Fourth Crusade his lineage became named Sanudo de Candia.

Agnes of France, renamed Anna, was Byzantine empress by marriage to Alexios II Komnenos and Andronikos I Komnenos. She was a daughter of Louis VII of France and Adèle of Champagne.

Michael I Komnenos Doukas, Latinized as Comnenus Ducas, and in modern sources often recorded as Michael I Angelos, a name he never used, was the founder and first ruler of the Despotate of Epirus from c. 1205 until his assassination in 1214/15.

The siege of Zara or siege of Zadar was the first major action of the Fourth Crusade and the first attack against a Catholic city by Catholic crusaders. The crusaders had an agreement with Venice for transport across the sea, but the price far exceeded what they were able to pay. Venice set the condition that the crusaders help them capture Zadar, a constant battleground between Venice on one side and Croatia and Hungary on the other, whose king, Emeric, pledged himself to join the Crusade. Although some of the crusaders refused to take part in the siege, the attack on Zadar began in November 1202 despite letters from Pope Innocent III forbidding such an action and threatening excommunication. Zadar fell on 24 November and the Venetians and the crusaders sacked the city. After wintering in Zadar, the Fourth Crusade continued its campaign, which led to the siege of Constantinople.

Constantine Laskaris may have been Byzantine Emperor for a few months from 1204 to early 1205. He is sometimes called "Constantine XI", a numeral now usually reserved for Constantine Palaiologos.

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by emperors of the Angelos dynasty between 1185 and 1204 AD. The Angeloi rose to the throne following the deposition of Andronikos I Komnenos, the last male-line Komnenos to rise to the throne. The Angeloi were female-line descendants of the previous dynasty. While in power, the Angeloi were unable to stop the invasions of the Turks by the Sultanate of Rum, the uprising and resurrection of the Bulgarian Empire, and the loss of the Dalmatian coast and much of the Balkan areas won by Manuel I Komnenos to the Kingdom of Hungary.

The sack of Constantinople occurred in April 1204 and marked the culmination of the Fourth Crusade. Crusader armies captured, looted, and destroyed parts of Constantinople, then the capital of the Byzantine Empire. After the capture of the city, the Latin Empire was established and Baldwin of Flanders was crowned Emperor Baldwin I of Constantinople in the Hagia Sophia.

The Siege of Constantinople in 1203 was a crucial episode of the Fourth Crusade, marking the beginning of a series of events that would ultimately lead to the fall of the Byzantine capital. The crusaders, diverted from their original mission to reclaim Jerusalem, found themselves in Constantinople, in support of the deposed emperor Isaac II Angelos and his son Alexios IV Angelos. The besieging forces, primarily composed of Western European knights faced initial setbacks, but their determination and advanced siege weaponry played a pivotal role in pressuring the Byzantine defenders.

Martin was the abbot of the Cistercian monastery of Pairis in Alsace, then part of the German kingdom in the Holy Roman Empire. Martin played a supporting role on the Fourth Crusade. He was a major source for the Historia Constantinopolitana, a history of the Fourth Crusade written by the monk Gunther of Pairis. Gunther's Historia serves as both a eulogy on the life of Martin and also an account of the translation of relics Martin brought to Pairis from the crusade. Gunther describes Martin as pleasant-looking, affable, eloquent, humble and wise.

Peter was an Italian Cistercian monk and prelate. He was the abbot of Rivalta from 1180 until 1185, abbot of Lucedio from 1185 until 1205, abbot of La Ferté from 1205 until 1206, bishop of Ivrea from 1206 until 1208 and patriarch of Antioch from 1209 until his death. He is known as Peter of Magnano, Peter of Lucedio or Peter of Ivrea.

The timeline of the Latin Empire is a chronological list of events of the history of the Latin Empire—the crusader state that developed on the ruins of the Byzantine Empire after the Fourth Crusade in the 13th century.