Nucleotides are organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules within all life-forms on Earth. Nucleotides are obtained in the diet and are also synthesized from common nutrients by the liver.

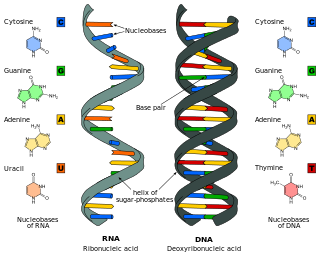

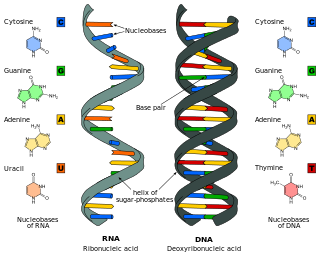

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself or by forming a template for the production of proteins. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) are nucleic acids. The nucleic acids constitute one of the four major macromolecules essential for all known forms of life. RNA is assembled as a chain of nucleotides. Cellular organisms use messenger RNA (mRNA) to convey genetic information that directs synthesis of specific proteins. Many viruses encode their genetic information using an RNA genome.

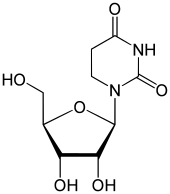

Thymine is one of the four nucleotide bases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The others are adenine, guanine, and cytosine. Thymine is also known as 5-methyluracil, a pyrimidine nucleobase. In RNA, thymine is replaced by the nucleobase uracil. Thymine was first isolated in 1893 by Albrecht Kossel and Albert Neumann from calf thymus glands, hence its name.

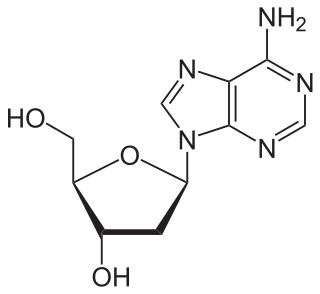

Nucleotide bases are nitrogen-containing biological compounds that form nucleosides, which, in turn, are components of nucleotides, with all of these monomers constituting the basic building blocks of nucleic acids. The ability of nucleobases to form base pairs and to stack one upon another leads directly to long-chain helical structures such as ribonucleic acid (RNA) and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). Five nucleobases—adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), thymine (T), and uracil (U)—are called primary or canonical. They function as the fundamental units of the genetic code, with the bases A, G, C, and T being found in DNA while A, G, C, and U are found in RNA. Thymine and uracil are distinguished by merely the presence or absence of a methyl group on the fifth carbon (C5) of these heterocyclic six-membered rings. In addition, some viruses have aminoadenine (Z) instead of adenine. It differs in having an extra amine group, creating a more stable bond to thymine.

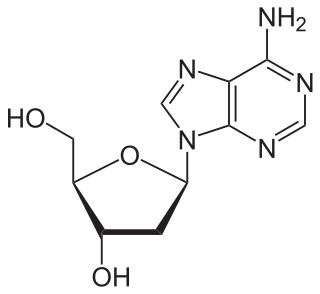

Nucleosides are glycosylamines that can be thought of as nucleotides without a phosphate group. A nucleoside consists simply of a nucleobase and a five-carbon sugar whereas a nucleotide is composed of a nucleobase, a five-carbon sugar, and one or more phosphate groups. In a nucleoside, the anomeric carbon is linked through a glycosidic bond to the N9 of a purine or the N1 of a pyrimidine. Nucleotides are the molecular building blocks of DNA and RNA.

In biochemistry, a ribonucleotide is a nucleotide containing ribose as its pentose component. It is considered a molecular precursor of nucleic acids. Nucleotides are the basic building blocks of DNA and RNA. Ribonucleotides themselves are basic monomeric building blocks for RNA. Deoxyribonucleotides, formed by reducing ribonucleotides with the enzyme ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), are essential building blocks for DNA. There are several differences between DNA deoxyribonucleotides and RNA ribonucleotides. Successive nucleotides are linked together via phosphodiester bonds.

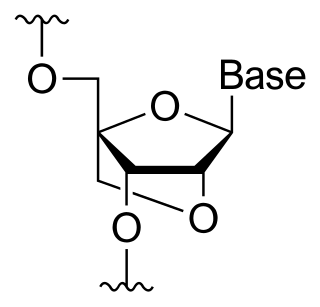

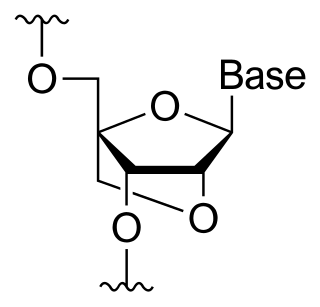

A locked nucleic acid (LNA), also known as bridged nucleic acid (BNA), and often referred to as inaccessible RNA, is a modified RNA nucleotide in which the ribose moiety is modified with an extra bridge connecting the 2' oxygen and 4' carbon. The bridge "locks" the ribose in the 3'-endo (North) conformation, which is often found in the A-form duplexes. This structure provides for increased stability against enzymatic degradation. LNA also offers improved specificity and affinity in base-pairing as a monomer or a constituent of an oligonucleotide. LNA nucleotides can be mixed with DNA or RNA residues in a oligonucleotide.

A nucleoside triphosphate is a nucleoside containing a nitrogenous base bound to a 5-carbon sugar, with three phosphate groups bound to the sugar. They are the molecular precursors of both DNA and RNA, which are chains of nucleotides made through the processes of DNA replication and transcription. Nucleoside triphosphates also serve as a source of energy for cellular reactions and are involved in signalling pathways.

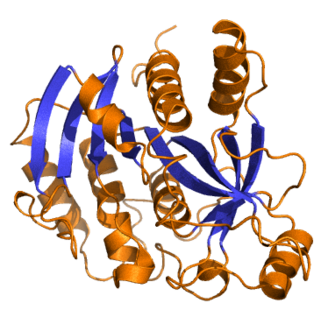

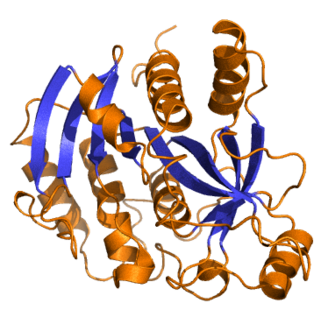

Purine nucleoside phosphorylase, PNP, PNPase or inosine phosphorylase is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the NP gene. It catalyzes the chemical reaction

Deoxycytidine kinase (dCK) is an enzyme which is encoded by the DCK gene in humans. dCK predominantly phosphorylates deoxycytidine (dC) and converts dC into deoxycytidine monophosphate. dCK catalyzes one of the initial steps in the nucleoside salvage pathway and has the potential to phosphorylate other preformed nucleosides, specifically deoxyadenosine (dA) and deoxyguanosine (dG), and convert them into their monophosphate forms. There has been recent biomedical research interest in investigating dCK's potential as a therapeutic target for different types of cancer.

Nucleic acid analogues are compounds which are analogous to naturally occurring RNA and DNA, used in medicine and in molecular biology research. Nucleic acids are chains of nucleotides, which are composed of three parts: a phosphate backbone, a pentose sugar, either ribose or deoxyribose, and one of four nucleobases. An analogue may have any of these altered. Typically the analogue nucleobases confer, among other things, different base pairing and base stacking properties. Examples include universal bases, which can pair with all four canonical bases, and phosphate-sugar backbone analogues such as PNA, which affect the properties of the chain . Nucleic acid analogues are also called xeno nucleic acids and represent one of the main pillars of xenobiology, the design of new-to-nature forms of life based on alternative biochemistries.

In enzymology, a preQ1 synthase (EC 1.7.1.13) is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reaction

Uridine-cytidine kinase 2 (UCK2) is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the UCK2 gene.

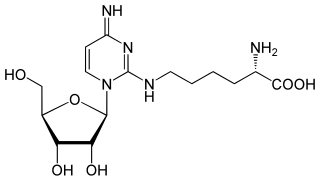

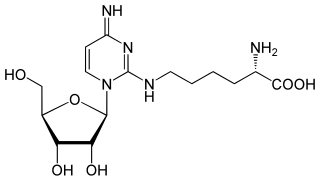

Lysidine is an uncommon nucleoside, rarely seen outside of tRNA. It is a derivative of cytidine in which the carbonyl is replaced by the amino acid lysine. The third position in the anti-codon of the Isoleucine-specific tRNA, is typically changed from a cytidine which would pair with guanosine to a lysidine which will base pair with adenosine. Lysidine improves translation fidelity because uridine cannot be used at this position even though it is a conventional partner for adenosine since it will also "wobble base pair" with guanosine. Lysidine is denoted as L or k2C.

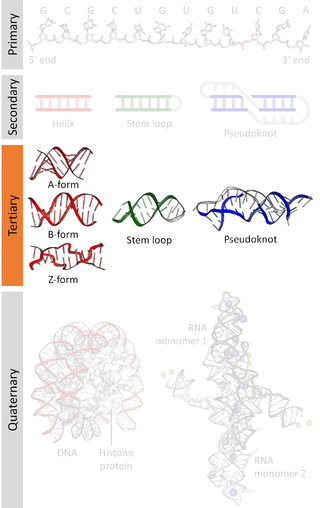

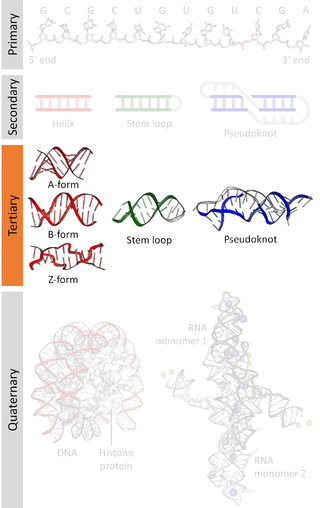

Nucleic acid tertiary structure is the three-dimensional shape of a nucleic acid polymer. RNA and DNA molecules are capable of diverse functions ranging from molecular recognition to catalysis. Such functions require a precise three-dimensional structure. While such structures are diverse and seemingly complex, they are composed of recurring, easily recognizable tertiary structural motifs that serve as molecular building blocks. Some of the most common motifs for RNA and DNA tertiary structure are described below, but this information is based on a limited number of solved structures. Many more tertiary structural motifs will be revealed as new RNA and DNA molecules are structurally characterized.

Nucleic acid structure refers to the structure of nucleic acids such as DNA and RNA. Chemically speaking, DNA and RNA are very similar. Nucleic acid structure is often divided into four different levels: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary.

Nucleic acid secondary structure is the basepairing interactions within a single nucleic acid polymer or between two polymers. It can be represented as a list of bases which are paired in a nucleic acid molecule. The secondary structures of biological DNAs and RNAs tend to be different: biological DNA mostly exists as fully base paired double helices, while biological RNA is single stranded and often forms complex and intricate base-pairing interactions due to its increased ability to form hydrogen bonds stemming from the extra hydroxyl group in the ribose sugar.

A bridged nucleic acid (BNA) is a modified RNA nucleotide. They are sometimes also referred to as constrained or inaccessible RNA molecules. BNA monomers can contain a five-membered, six-membered or even a seven-membered bridged structure with a "fixed" C3'-endo sugar puckering. The bridge is synthetically incorporated at the 2', 4'-position of the ribose to afford a 2', 4'-BNA monomer. The monomers can be incorporated into oligonucleotide polymeric structures using standard phosphoramidite chemistry. BNAs are structurally rigid oligo-nucleotides with increased binding affinities and stability.

Non-canonical base pairs are planar hydrogen bonded pairs of nucleobases, having hydrogen bonding patterns which differ from the patterns observed in Watson-Crick base pairs, as in the classic double helical DNA. The structures of polynucleotide strands of both DNA and RNA molecules can be understood in terms of sugar-phosphate backbones consisting of phosphodiester-linked D 2’ deoxyribofuranose sugar moieties, with purine or pyrimidine nucleobases covalently linked to them. Here, the N9 atoms of the purines, guanine and adenine, and the N1 atoms of the pyrimidines, cytosine and thymine, respectively, form glycosidic linkages with the C1’ atom of the sugars. These nucleobases can be schematically represented as triangles with one of their vertices linked to the sugar, and the three sides accounting for three edges through which they can form hydrogen bonds with other moieties, including with other nucleobases. The side opposite to the sugar linked vertex is traditionally called the Watson-Crick edge, since they are involved in forming the Watson-Crick base pairs which constitute building blocks of double helical DNA. The two sides adjacent to the sugar-linked vertex are referred to, respectively, as the Sugar and Hoogsteen edges.

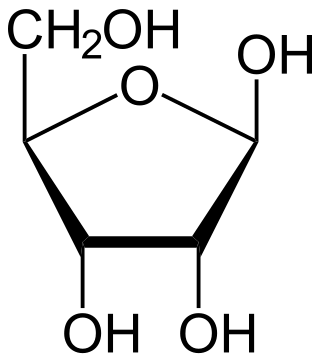

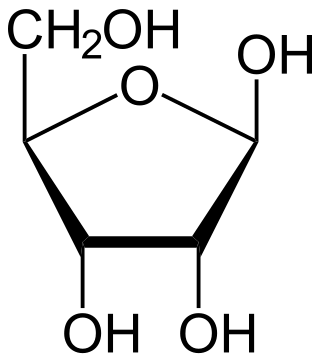

Ribose is a simple sugar and carbohydrate with molecular formula C5H10O5 and the linear-form composition H−(C=O)−(CHOH)4−H. The naturally-occurring form, d-ribose, is a component of the ribonucleotides from which RNA is built, and so this compound is necessary for coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. It has a structural analog, deoxyribose, which is a similarly essential component of DNA. l-ribose is an unnatural sugar that was first prepared by Emil Fischer and Oscar Piloty in 1891. It was not until 1909 that Phoebus Levene and Walter Jacobs recognised that d-ribose was a natural product, the enantiomer of Fischer and Piloty's product, and an essential component of nucleic acids. Fischer chose the name "ribose" as it is a partial rearrangement of the name of another sugar, arabinose, of which ribose is an epimer at the 2' carbon; both names also relate to gum arabic, from which arabinose was first isolated and from which they prepared l-ribose.