Related Research Articles

John Milton was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem Paradise Lost, written in blank verse and including over ten books, was written in a time of immense religious flux and political upheaval. It addressed the fall of man, including the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and God's expulsion of them from the Garden of Eden. Paradise Lost elevated Milton's reputation as one of history's greatest poets. He also served as a civil servant for the Commonwealth of England under its Council of State and later under Oliver Cromwell.

Polygamy is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is married to more than one husband at a time, it is called polyandry. In sociobiology and zoology, researchers use polygamy in a broad sense to mean any form of multiple mating.

Polygamy was practiced by leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for more than half of the 19th century, and practiced publicly from 1852 to 1890 by between 20 and 30 percent of Latter-day Saint families.

John Selden was an English jurist, a scholar of England's ancient laws and constitution and scholar of Jewish law. He was known as a polymath; John Milton hailed Selden in 1644 as "the chief of learned men reputed in this land".

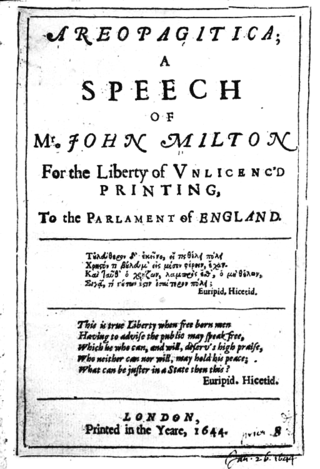

Areopagitica; A speech of Mr. John Milton for the Liberty of Unlicenc'd Printing, to the Parlament of England is a 1644 prose polemic by the English poet, scholar, and polemical author John Milton opposing licensing and censorship. Areopagitica is among history's most influential and impassioned philosophical defences of the principle of a right to freedom of speech and expression. Many of its expressed principles have formed the basis for modern justifications of that right.

Spiritual wifery is a term first used in America by the Immortalists in and near the Blackstone Valley of Rhode Island and Massachusetts in the 1740s. The term describes the idea that certain people are divinely destined to meet and share their love after receiving a spiritual confirmation, and regardless of previous civil marital bonds. Its history in Europe among various Christian primitivistic movements has been well documented. The followers of Jacob Cochran as early as 1818 used "spiritual wifery" to describe their religious doctrine of free love. Often confused with polygamy, spiritual wifery among the Cochranites was the practice in which communal mates were temporarily assigned and reassigned, either by personal preference or religious authority.

The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates is a book by John Milton, in which he defends the right of people to execute a guilty sovereign, whether tyrannical or not.

Tetrachordon was published by John Milton with his Colasterion on 4 March 1645. The title symbolizes Milton's attempt to connect four passages of Biblical scripture to rationalize the legalization of divorce.

Milton's divorce tracts refer to the four interlinked polemical pamphlets—The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce, The Judgment of Martin Bucer, Tetrachordon, and Colasterion—written by John Milton from 1643 to 1645. They argue for the legitimacy of divorce on grounds of spousal incompatibility. Arguing for divorce at all, let alone a version of no-fault divorce, was extremely controversial and religious figures sought to ban his tracts. Although the tracts were met with nothing but hostility and he later rued publishing them in English at all, they are important for analysing the relationship between Adam and Eve in his epic Paradise Lost. Spanning three years characterised by turbulent changes in the English printing business, they also provide an important context for the publication of Areopagitica, Milton's most famous work of prose.

Colasterion was published by John Milton with his Tetrachordon on 4 March 1645. The tract is a response to an anonymous pamphlet attacking the first edition of The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce. Milton makes no new arguments, but harshly takes to task the "trivial author".

Judgement of Martin Bucer by John Milton was published on 15 July 1644. The work consists mostly of Milton's translations of pro-divorce arguments from Martin Bucer's De Regno Christi. By finding support for his views among orthodox writers, Milton hoped to sway the members of Parliament Protestant ministers who had condemned him.

Polygamy is "the practice or custom of having more than one wife or husband at the same time." Polygamy has been practiced by many cultures throughout history.

Joseph Smith, the founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, privately taught and practiced polygamy. After Smith's death in 1844, the church he established splintered into several competing groups. Disagreement over Smith's doctrine of "plural marriage" has been among the primary reasons for multiple church schisms.

Defension Secunda was a 1654 political tract by John Milton, a sequel to his Defensio pro Populo Anglicano. It is a defence of the Parliamentary regime, then controlled by Oliver Cromwell; and also defense of his own reputation against a royalist tract published under the name Salmasius in 1652, and other criticism lodged against him.

The Ready and Easy Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth was a political tract by John Milton published in London at the end of February 1660. The full title is "The readie & easie way to establish a Free Commonwealth, and the excellence therof compar'd with the inconveniences and dangers of readmitting kingship in this nation. The author J[ohn] M[ilton]". In the tract, Milton warns against the dangers inherent in a monarchical form of government. A second edition, published in March 1660, steps up the prophetic rhetoric against a monarchy. The book can be seen as an expression of Milton's own antimonarchism.

The religious views of John Milton influenced many of his works focusing on the nature of religion and of the divine. He differed in important ways from the Calvinism with which he is associated, particularly concerning the doctrines of grace and predestination. The unusual nature of his own Protestant Christianity has been characterized as both Puritan and Independent.

John Milton wrote poetry during the English Renaissance. He was born on 9 December 1608 to John and Sara Milton. Only three of their children survived infancy. Anne was the oldest, John was the middle child, and Christopher was the youngest.

John Milton was involved in many relationships, romantic and not, that impacted his various works and writings.

The Republic of Afghanistan, which is an Islamic Republic under Sharia Law, allows for polygyny. Afghan men may take up to four wives, as Islam allows for such. A man must treat all of his wives equally; however, it has been reported that these regulations are rarely followed. While the Qur'an states that a man is allowed a maximum of four wives, there is an unspecified number of women allowed to be his 'concubines'. These women are considered unprotected and need a man as a guardian.

In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, marriage between a man and a woman is considered to be "ordained of God". Marriage is thought to consist of a covenant between the man, the woman, and God. The church teaches that in addition to civil marriage, which ends at death, a man and woman can enter into a celestial marriage, performed in a temple by priesthood authority, whereby the marriage and parent–child relationships resulting from the marriage will last forever in the afterlife.

References

- Miller, Leo. John Milton among the Polygamophiles. New York: Loewenthal Press, 1974.

- Milton, John. Complete Prose Works of John Milton Vol II ed. Don Wolfe. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959.

- Patterson, Annabel. "Milton, Marriage and Divorce" in A Companion to Milton. Ed. Thomas Corns. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003.