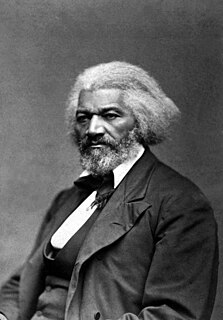

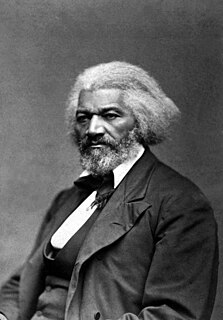

Frederick Douglass was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became a national leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York, gaining note for his oratory and incisive antislavery writings. In his time, he was described by abolitionists as a living counter-example to slaveholders' arguments that slaves lacked the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens. Northerners at the time found it hard to believe that such a great orator had once been a slave.

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, was the movement to end slavery. This term can be used both formally and informally. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and set slaves free. King Charles I of Spain, usually known as Emperor Charles V, was following the example of Louis X of France, who had abolished slavery within the Kingdom of France in 1315. He passed a law which would have abolished colonial slavery in 1542, although this law was not passed in the largest colonial states, and it was not enforced as a result. In the late 17th century, the Roman Catholic Church officially condemned the slave trade in response to a plea by Lourenço da Silva de Mendouça, and it was also vehemently condemned by Pope Gregory XVI in 1839. The abolitionist movement only started in the late 18th century, however, when English and American Quakers began to question the morality of slavery. James Oglethorpe was among the first to articulate the Enlightenment case against slavery, banning it in the Province of Georgia on humanitarian grounds, and arguing against it in Parliament, and eventually encouraging his friends Granville Sharp and Hannah More to vigorously pursue the cause. Soon after his death in 1785, Sharp and More united with William Wilberforce and others in forming the Clapham Sect.

Slavery in the United States was the legal institution of human chattel enslavement, primarily of Africans and African Americans, that existed in the United States of America from the beginning of the nation in 1776 until passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. Slavery had been practiced in British America from early colonial days, and was legal in all thirteen colonies at the time of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property and could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until 1865. As an economic system, slavery was largely replaced by sharecropping and convict leasing.

Mary Ann Shadd Cary was an American-Canadian anti-slavery activist, journalist, publisher, teacher, and lawyer. She was the first Black woman publisher in North America and the first woman publisher in Canada.

James William Charles Pennington was an African-American orator, minister, writer, and abolitionist active in Brooklyn, New York. He escaped at the age of 19 from slavery in western Maryland and reached New York. After working in Brooklyn and gaining some education, he was admitted to Yale University as its first black student. He completed studies and was ordained as a minister in the Congregational Church, later also serving in Presbyterian churches for congregations in Hartford, Connecticut; and New York. After the Civil War, he served congregations in Natchez, Mississippi; Portland, Maine; and Jacksonville, Florida.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is an 1845 memoir and treatise on abolition written by famous orator and former slave Frederick Douglass during his time in Lynn, Massachusetts. It is generally held to be the most famous of a number of narratives written by former slaves during the same period. In factual detail, the text describes the events of his life and is considered to be one of the most influential pieces of literature to fuel the abolitionist movement of the early 19th century in the United States.

In United States history, a free Negro or free black was the legal status, in the geographic area of the United States, of blacks who were not slaves. It included both freed slaves (freedmen) and those who had been born free.

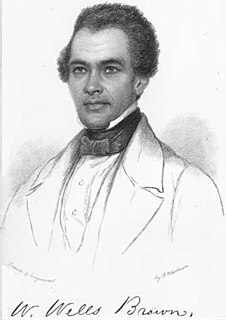

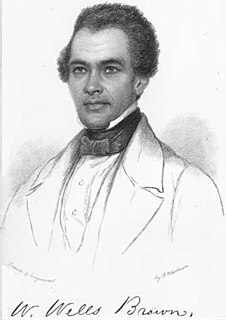

William Wells Brown was a prominent African-American abolitionist lecturer, novelist, playwright, and historian in the United States. Born into slavery in Montgomery County, Kentucky, near the town of Mount Sterling, Brown escaped to Ohio in 1834 at the age of 19. He settled in Boston, Massachusetts, where he worked for abolitionist causes and became a prolific writer. While working for abolition, Brown also supported causes including: temperance, women's suffrage, pacifism, prison reform, and an anti-tobacco movement. His novel Clotel (1853), considered the first novel written by an African American, was published in London, England, where he resided at the time; it was later published in the United States.

Antebellum South Carolina is typically defined by historians as South Carolina during the period between the War of 1812, which ended in 1815, and the American Civil War, which began in 1861.

Rev. Jermain Wesley Loguen, born Jarm Logue, in slavery, was an African-American abolitionist and bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, and an author of a slave narrative.

The systematic enslavement of African people in the United States began in New York as part of the Dutch slave trade. The Dutch West India Company imported eleven African slaves to New Amsterdam in 1626, with the first slave auction held in New Amsterdam in 1655. With the second-highest proportion of any city in the colonies after Charleston, South Carolina, more than 42 percent of New York City households held slaves, often as domestic servants and laborers by 1703. Others worked as artisans or in shipping and various trades in the city. Slaves were also used in farming on Long Island and in the Hudson Valley, as well as the Mohawk Valley region.

Thomas James (1804–1891) had been a slave who became an African Methodist Episcopal Zion minister, abolitionist, administrator and author. He was active in New York and Massachusetts with abolitionists, and served with the American Missionary Association and the Union Army during the American Civil War to supervise the contraband camp in Louisville, Kentucky. After the war, he held national offices in the AME Church and was a missionary to black churches in Ohio. While in Massachusetts, he challenged the railroad's custom of forcing blacks into second-class carriages and won a reversal of the rule in the State Supreme Court. He wrote a short memoir published in 1886.

Slavery in Maryland lasted around 200 years, from its beginnings in 1642 when the first Africans were brought as slaves to St. Mary's City, to its end after the Civil War. While Maryland developed similarly to neighboring Virginia, slavery declined here as an institution earlier, and it had the largest free black population by 1860 of any state. The early settlements and population centers of the province tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay. Maryland planters cultivated tobacco as the chief commodity crop, as the market was strong in Europe. Tobacco was labor-intensive in both cultivation and processing, and planters struggled to manage workers as tobacco prices declined in the late 17th century, even as farms became larger and more efficient. At first, indentured servants from England supplied much of the necessary labor but, as their economy improved at home, fewer made passage to the colonies. Maryland colonists turned to importing indentured and enslaved Africans to satisfy the labor demand.

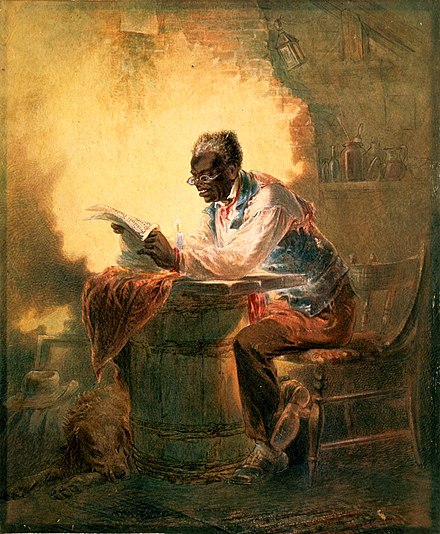

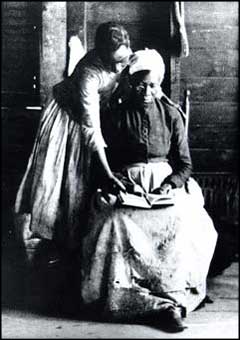

Anti literacy laws in many slave states before and during the American Civil War, affected slaves, freedmen, and in some cases all people of color. Some laws arose from concerns that literate slaves could forge the documents required to escape to a free state. According to William M. Banks, "Many slaves who learned to write did indeed achieve freedom by this method. The wanted posters for runaways often mentioned whether the escapee could write." Anti-literacy laws also arose from fears of slave insurrection, particularly around the time of abolitionist David Walker's 1829 publication of Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World, which openly advocated rebellion, and Nat Turner's slave rebellion of 1831.

John Sella Martin was a noted abolitionist in Boston, Massachusetts and a pastor, who had escaped from slavery in Alabama. He was a leading African-American preacher and activist for equality before the American Civil War, traveling to England to lecture against slavery. When he returned, he preached in Presbyterian churches in Washington, DC.

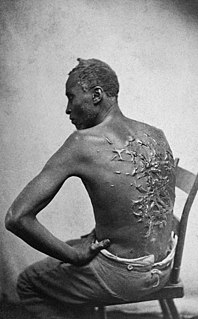

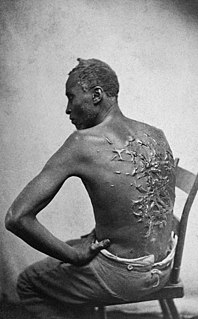

The treatment of slaves in the United States varied by time and place, but was generally brutal, especially on plantations. Whipping and rape were routine, but usually not in front of white outsiders, or even the plantation owner's family. A slave could not be a witness against a white; slaves were sometimes required to whip other slaves, even family members. There were also businesses to which a slave owner could turn over the whipping. Families were often split up by the sale of one or more members. There were certainly some kind and relatively enlightened slave owners — Nat Turner said his master was kind — but not on large plantations. Only a small minority of slaves received anything resembling decent treatment, and even that could vanish on such occasion as an owner's death. As put by William T. Allan, a slaveowner's abolitionist son who could not safely return to Alabama, "cruelty was the rule, and kindness the exception".

Abolitionism in the United States of America was the movement which sought to end slavery in the United States immediately, active both before and during the American Civil War. In the Americas and western Europe, abolitionism was a movement which sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and set slaves free. In the 18th century, enlightenment thinkers condemned slavery on humanistic grounds and English Quakers and some Evangelical denominations condemned slavery as un-Christian. At that time, most slaves were Africans, but thousands of Native Americans were also enslaved. In the 18th century, as many as six million Africans were transported to the Americas as slaves, at least a third of them on British ships to North America. The colony of Georgia originally prohibited slavery.

Margaret Crittendon Douglass was a Southern white woman who served one month in jail in 1854 for teaching free black children to read in Norfolk, Virginia. Refusing to hire a defense attorney, she defended herself in court and later published a book about her experiences. The case drew public attention to the highly restrictive laws against black literacy in the pre-Civil War American South.

James Bradley was an African slave in the United States who purchased his freedom and became an anti-slavery activist in Ohio.

Abolitionism in New Bedford, Massachusetts is about the ways in which the residents of New Bedford, Massachusetts fought for the end of slavery and provided support to fugitive slaves who sought freedom. Positioned on the East Coast of the United States, New Bedford was called the "whaling capital of the world". Ships were returning to port, with crew members with diverse backgrounds, languages, and ethnicity. This made it easy for fugitive slaves to "mix in" with crew members. The whaling and shipping industries were also uniquely open to people of color.