Uzbekistan is a landlocked country in Central Asia. It is itself surrounded by five landlocked countries: Kazakhstan to the north; Kyrgyzstan to the northeast; Tajikistan to the southeast; Afghanistan to the south, Turkmenistan to the south-west. Its capital and largest city is Tashkent. Uzbekistan is part of the Turkic languages world, as well as a member of the Organization of Turkic States. While the Uzbek language is the majority spoken language in Uzbekistan, Russian is widely used as an inter-ethnic tongue and in government. Islam is the majority religion in Uzbekistan, most Uzbeks being non-denominational Muslims. In ancient times it largely overlapped with the region known as Sogdia, and also with Bactria.

The Uzbeks are a Turkic ethnic group native to the wider Central Asian region, being among the largest Turkic ethnic groups in the area. They comprise the majority population of Uzbekistan, next to Kazakh and Karakalpak minorities, and also form minority groups in Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Russia, and China. Uzbek diaspora communities also exist in Turkey, Saudi Arabia, United States, Ukraine, Pakistan, and other countries.

Chagatai, also known as Turki, Eastern Turkic, or Chagatai Turkic, is an extinct Turkic language that was once widely spoken across Central Asia. It remained the shared literary language in the region until the early 20th century. It was used across a wide geographic area including western or Russian Turkestan, Eastern Turkestan, Crimea, the Volga region, etc. Chagatai is the ancestor of the Uzbek and Uyghur languages. Turkmen, which is not within the Karluk branch but in the Oghuz branch of Turkic languages, was nonetheless heavily influenced by Chagatai for centuries.

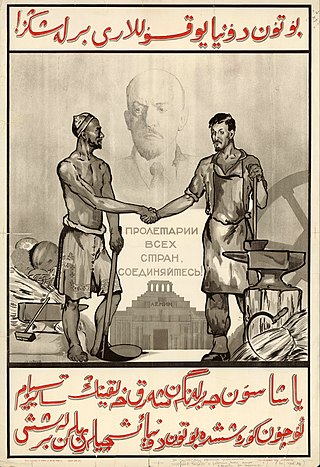

The Basmachi movement was an uprising against Imperial Russian and Soviet rule in Central Asia by rebel groups inspired by Islamic beliefs.

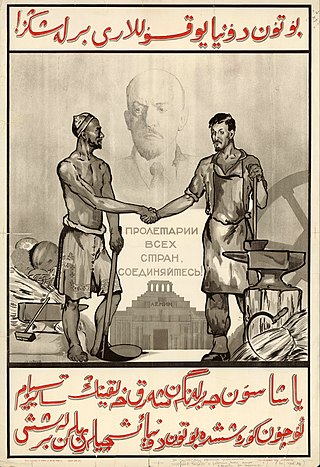

The flags of the Soviet Socialist Republics were all defaced versions of the flag of the Soviet Union, which featured a golden hammer and sickle and a gold-bordered red star on a red field.

Bukharan Jews, in modern times called Bukharian Jews, are the Mizrahi Jewish sub-group of Central Asia that historically spoke Bukharian, a Judeo-Persian dialect of the Tajik language, in turn a variety of the Persian language. Their name comes from the former Muslim-Uzbek polity Emirate of Bukhara, which once had a sizable Jewish population.

The Jadids were a political, religious, and cultural movement of Muslim modernist reformers within the Russian Empire in the late 19th and early 20th century. They normally referred to themselves by the Turkic terms Taraqqiparvarlar ("progressives"), Ziyalilar ("intellectuals"), or simply Yäşlär/Yoshlar ("youth"). The Jadid movement advocated for an Islamic social and cultural reformation through the revival of pristine Islamic beliefs and teachings, while simultaneously engaging with modernity. Jadids maintained that Turks in Tsarist Russia had entered a period of moral and societal decay that could only be rectified by the acquisition of a new kind of knowledge and modernist, European-modeled cultural reform.

The Emirate of Bukhara was a Muslim-Uzbek polity in Central Asia that existed from 1785 to 1920 in what is now Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. It occupied the land between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, known formerly as Transoxiana. Its core territory was the fertile land along the lower Zarafshon river, and its urban centres were the ancient cities of Samarqand and the emirate's capital, Bukhara. It was contemporaneous with the Khanate of Khiva to the west, in Khwarazm, and the Khanate of Kokand to the east, in Fergana. In 1920, it ceased to exist with the establishment of the Bukharan People's Soviet Republic.

National delimitation in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was the process of specifying well-defined national territorial units from the ethnic diversity of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) and its subregions.

The Tajik language has been written in three alphabets over the course of its history: an adaptation of the Perso-Arabic script, an adaptation of the Latin script and an adaptation of the Cyrillic script. Any script used specifically for Tajik may be referred to as the Tajik alphabet, which is written as алифбои тоҷикӣ in Cyrillic characters, الفبای تاجیکی with Perso-Arabic script and alifboji toçikī in Latin script.

Soviet Central Asia was the part of Central Asia administered by the Russian SFSR and then the Soviet Union between 1918 and 1991, when the Central Asian republics declared independence. It is nearly synonymous with Russian Turkestan in the Russian Empire. Soviet Central Asia went through many territorial divisions before the current borders were created in the 1920s and 1930s.

After it was established on most of the territory of the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union remained the world's largest country until it was dissolved in 1991. It covered a large part of Eastern Europe while also spanning the entirety of the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Northern Asia. During this time, Islam was the country's second-largest religion; 90% of Muslims in the Soviet Union were adherents of Sunni Islam, with only around 10% adhering to Shia Islam. Excluding the Azerbaijan SSR, which had a Shia-majority population, all of the Muslim-majority Union Republics had Sunni-majority populations. In total, six Union Republics had Muslim-majority populations: the Azerbaijan SSR, the Kazakh SSR, the Kyrgyz SSR, the Tajik SSR, the Turkmen SSR, and the Uzbek SSR. There was also a large Muslim population across Volga–Ural and in the northern Caucasian regions of the Russian SFSR. Across Siberia, Muslims accounted for a significant proportion of the population, predominantly through the presence of Tatars. Many autonomous republics like the Karakalpak ASSR, the Chechen-Ingush ASSR, the Bashkir ASSR and others also had Muslim majorities.

The Young Bukharans or Mladobukharans were a secret society founded in Bukhara in 1909, which was part of the jadidist movement seeking to reform and modernize Central Asia along Western-scientific lines.

Shukrullo was an Uzbek poet.

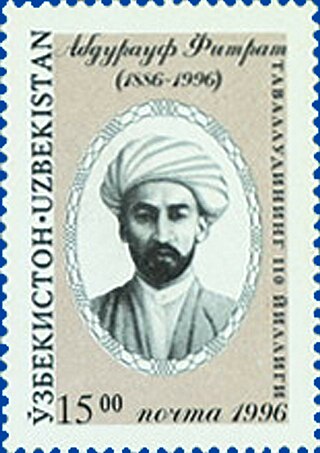

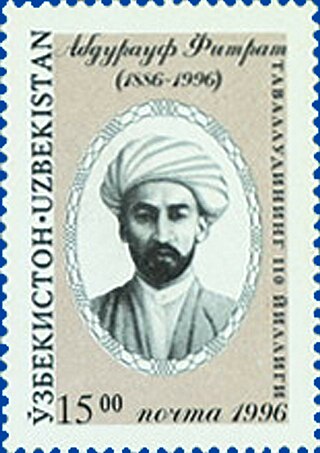

Abdurauf Fitrat was an Uzbek author, journalist, politician and public intellectual in Central Asia under Russian and Soviet rule.

The Uzbek Soviet Encyclopedia is the largest and most comprehensive encyclopedia in the Uzbek language, comprising 14 volumes. It is the first general-knowledge encyclopedia in Uzbek.

Edward A. Allworth was an American historian specializing in Central Asia. Allwarth is widely regarded as the West’s leading scholar on Central Asian studies. He extensively studied the various ethnic groups of the region, including Uzbeks, Tajiks, and Bukharan Jews. He wrote numerous books on the history of Central Asia.

Sorojon Mikhailovna Yusufova was a Tajik geologist and academic of the Soviet era.

Timur Kocaoğlu is an American and Turkish historian and political scientist of Uzbek descent. He was the first Uzbek scientist to defend his doctoral dissertation at Columbia University. He was born in Istanbul in 1947 in the family of Osman Kocaoğlu, one of the leaders of the Bukharan People's Soviet Republic. In 1971, he graduated from the Faculty of Literature, Department of Turkish Language and Literature of Istanbul University. In 1977, he studied at the Department of Arts, Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures (MELAC) at Columbia University, and in 1979 he defended two master's theses in political science at the Department of International Studies of Columbia University. In 1982, he defended his doctoral dissertation on the topic "National Identity in Soviet Central Asian Prose Fiction of the Post-Stalin Period: 1953-1982" under the scientific supervision of the famous professor Edward Allworth, who was founding director at Columbia of both the Program on Soviet Nationality Problems and the Center for the Study of Central Asia. After Timur Kocaoğlu defended this dissertation, he worked at Radio Liberty for many years.

Oyina was a bilingual Turki-Persian newspaper published from Samarkand, Russian Turkestan 1913-1915. The newspaper was published by Mahmudkhodja Behbudiy. It functioned as an organ of the Jadid social reform movement.