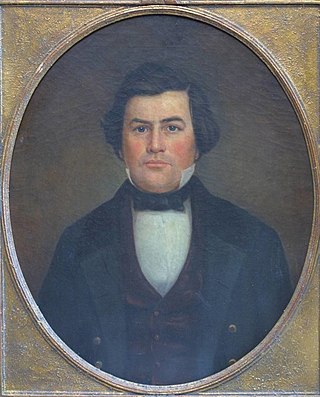

Biography

Edward W. Gantt was born in Maury County, Tennessee in 1829. His father, George, was a preacher and teacher. [2] Becoming a lawyer, Gantt practiced in Williamsport, Tennessee, and was along with his brother was a delegate to the Nashville Convention in 1850, which considered secession. [2] Gantt was one of the convention's youngest delegates and did not participate extensively. In 1854 [2] or 1853, he moved to Washington, Arkansas, where he also practiced law. Gantt had ambitions to become a prominent figure, and did not believe that Tennessee or eastern Arkansas gave him an adequate opportunity for that. Gantt was elected as prosecuting attorney for the Sixth Judicial District of Arkansas in 1854, 1856, and 1858. He married Margaret Reid in 1855; the couple had four children. [2] Her family was prominent in Dallas County, Arkansas. In 1858, he was reported to own three carriages, eight slaves, and $10,000 of real estate. As an opponent of Arkansas's ruling political "Family", Gantt ran for a seat in the United States House of Representatives in 1860. His campaign received the support of Thomas C. Hindman. [2] The Democratic Party was unable to decide on a nominee between Gantt and Charles B. Mitchel, so both candidates ran. Gantt won the general election, [2] polling at 54 percent.

Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 United States presidential election, and Gantt began canvassing northern and western Arkansas with secessionist speeches. [2] Gantt's speeches focused on the claimed risks that the culture of the northern United States presented to southern ideals of honor, pride, and freedom, although the historian Randy Finley questions whether Gantt actually believed his rhetoric. In November, both he and Hindman made inflammatory speeches to the Arkansas General Assembly. Arkansas seceded in early 1861, and joined the Confederate States of America in May. [2] Gantt never took office in the United States House of Representatives, and was also elected to the Confederate States Congress. He preferred a military command to a legislative office though. In late July, he was elected colonel of the 12th Arkansas Infantry Regiment; Gantt had previously requested to be made a major general.

He and his regiment were transferred to Columbus, Kentucky. On November 7, the 12th Arkansas remained in reserve at the Battle of Belmont, but Gantt was badly wounded during an artillery duel. [2] In December, another regiment was added to Gantt's command, and he and his men were transferred to the defenses of the Island Number 10 and New Madrid, Missouri, area. Gantt's superior, Leonidas Polk, recommended him for promotion to brigadier general, but the request was denied by Judah P. Benjamin, the Confederate States Secretary of War. General P. G. T. Beauregard appointed Gantt as an acting brigadier general early the next year. In early April, the Confederate defenses at Island Number 10 collapsed, and Gantt surrendered at Tiptonville, Tennessee, on April 8. He was imprisoned at Fort Warren until August 27, when he was exchanged.

Back home in Arkansas, Gantt awaited another military assignment, but did not receive one. Rumors of a drinking problem had spread, and there were also claims that he flirted with the wives of other officers. Believing that the Confederacy no longer offered him a chance at prominence, Gantt made his way to the Union lines at Vicksburg, Mississippi, and surrendered. [2] He met with Lincoln the next month, and then returned to Arkansas, where he advocated for Arkansans to reject the Confederacy. On December 11, he received the first pardon given by Lincoln to a Confederate officer, Gantt spoke against the Confederacy, slavery, and secession, and in 1863 and 1864 gave speeches in the northern United States designed to strengthen support in the Union for continuing the war. [2] Lincoln proposed the ten percent plan for returning the seceded states to the Union, and Gantt promoted this plan in Arkansas; his defection from the Confederacy and support for the Union earned him the disgust of many southerners.

In March 1865, the Freedmen's Bureau was formed, and the war was mostly over by the next month. [2] According to Finley, with the war over, Gantt opposed giving many Arkansas Confederates pardons; Finley suggests that Gantt was still unhappy over his lack of promotions in Confederate service. However, the historian Carl Moneyhon states that Gantt advocated pardoning some Arkansas Confederates to build support for the Unionist government of the state, with Gantt specifically asking for the pardon of Augustus H. Garland. In September, Gantt became the general superintendent of the Freedmen's Bureau for the Southwest District of Arkansas. In this role, he oversaw the relation between freed slaves and white Arkansans in his district; [2] he spent much time reviewing and mediating labor contracts. Gantt also organized fundraising for a hospital, supported education for former slaves, and encouraged African Americans in his district to have formal marriages. He also attempted to end "bodily coercion" as a means of enforcing labor contracts in his district.

In 1866, Gantt left his role with the Freedmen's Bureau and moved to Little Rock. His work with the Bureau had made him unpopular with Arkansas's class of white elites, which would block his hopes for higher political office. From 1868 to 1870, he was the regional prosecuting attorney. In this role, he integrated juries with African Americans, and tried to make the judicial system fair for both races. Gantt received death threats, sometimes carried seven weapons on his person, and kept his house dark after sundown. In 1868 or 1869, he had been badly beaten for his stances. [2] Gantt opposed the activities of the Ku Klux Klan and in 1867 and 1868 supported Ulysses S. Grant's presidential election campaign. Gantt resigned his role as prosecuting attorney in 1870, although he continued to prosecute occasional cases. Powell Clayton, the governor of Arkansas, tasked Gantt in 1873 with compiling Arkansas's legal code. While continuing this work, Gantt died in Little Rock of a heart attack on June 10, 1874, and was buried in Tulip.