The English-only movement, also known as the Official English movement, is a political movement that advocates for the use of only the English language in official United States government operations through the establishment of English as the only official language in the United States. The United States has never had a legal policy proclaiming an official national language. However, at some times and places, there have been various moves to promote or require the use of English, such as in Native American boarding schools.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, also known as the Hart–Celler Act and more recently as the 1965 Immigration Act, is a federal law passed by the 89th United States Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The law abolished the National Origins Formula, which had been the basis of U.S. immigration policy since the 1920s. The act removed de facto discrimination against Southern and Eastern Europeans, Asians, as well as other non-Western and Northern European ethnic groups from American immigration policy.

Michael Makoto "Mike" Honda is an American politician and former educator. A member of the Democratic Party, he served in Congress from 2001 to 2017.

United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court which held that "a child born in the United States, of parents of Chinese descent, who, at the time of his birth, are subjects of the Emperor of China, but have a permanent domicil and residence in the United States, and are there carrying on business, and are not employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China", automatically became a U.S. citizen at birth. This decision established an important precedent in its interpretation of the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

The Jones–Shafroth Act —also known as the Jones Act of Puerto Rico, Jones Law of Puerto Rico, or as the Puerto Rican Federal Relations Act of 1917— was an Act of the United States Congress, signed by President Woodrow Wilson on March 2, 1917. The act superseded the Foraker Act and granted U.S. citizenship to anyone born in Puerto Rico on or after April 11, 1899. It also created the Senate of Puerto Rico, established a bill of rights, and authorized the election of a Resident Commissioner to a four-year term. The act also exempted Puerto Rican bonds from federal, state, and local taxes regardless of where the bondholder resides.

Voting rights of citizens in the District of Columbia differ from the rights of citizens in each of the 50 U.S. states. The Constitution grants each state voting representation in both houses of the United States Congress. As the federal capital, the District of Columbia is a special federal district, not a state, and therefore does not have voting representation in Congress. The Constitution grants Congress exclusive jurisdiction over the District in "all cases whatsoever".

The Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act, known as the DREAM Act, is a United States legislative proposal to grant temporary conditional residency, with the right to work, to illegal immigrants who entered the United States as minors—and, if they later satisfy further qualifications, they would attain permanent residency.

The Border Protection, Anti-terrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act of 2005 was a bill in the 109th United States Congress. It was passed by the United States House of Representatives on December 16, 2005, by a vote of 239 to 182, but did not pass the Senate. It was also known as the "Sensenbrenner Bill," for its sponsor in the House of Representatives, Wisconsin Republican Jim Sensenbrenner. The bill was the catalyst for the 2006 U.S. immigration reform protests and was the first piece of legislation passed by a house of Congress in the United States illegal immigration debate. Development and the effect of the bill was featured in "The Senate Speaks", Story 11 in How Democracy Works Now: Twelve Stories a documentary series from filmmaking team Shari Robertson and Michael Camerini.

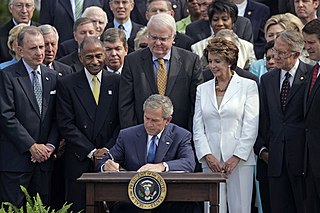

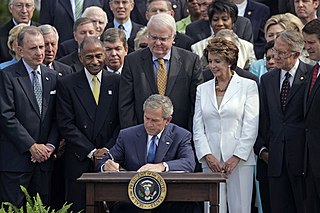

The Naturalization Act of 1906 was an act of the United States Congress signed into law by Theodore Roosevelt that revised the Naturalization Act of 1870 and required immigrants to learn English in order to become naturalized citizens. The bill was passed on June 29, 1906, and took effect September 27, 1906. It was repealed and replaced by the Nationality Act of 1940. It was modified by the Immigration Act of 1990.

The Inhofe Amendment was an amendment to the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2006, a United States Senate bill that would have changed current immigration law allowing more immigrants into the United States. The amendment was passed by the Senate on May 18, 2006 by a vote of 62–35. The bill did not pass the United States House of Representatives.

The Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act was a United States Senate bill introduced in the 109th Congress (2005–2006) by Sen. Arlen Specter [PA] on April 7, 2006. Co-sponsors, who signed on the same day, were Sen. Chuck Hagel [NE], Sen. Mel Martínez [FL], Sen. John McCain [AZ], Sen. Ted Kennedy [MA], Sen. Lindsey Graham [SC], and Sen. Sam Brownback [KS].

Birthright citizenship in the United States is United States citizenship acquired by a person automatically, by operation of law. This takes place in two situations: by virtue of the person's birth within United States territory or because one or both of their parents is a US citizen. Birthright citizenship contrasts with citizenship acquired in other ways, for example by naturalization.

The Violent Radicalization and Homegrown Terrorism Prevention Act of 2007 was a bill sponsored by Rep. Jane Harman (D-CA) in the 110th United States Congress. Its stated purpose is to deal with "homegrown terrorism and violent radicalization" by establishing a national commission, establishing a center for study, and cooperating with other nations.

In the early years of its existence, the United States had no formal immigration laws, but established clear naturalization laws. Anyone who wanted to vote or hold elective office had to be naturalized. Only those who went through the naturalization process and became a citizen could vote or hold elective office.

The Puerto Rico Democracy Act is a bill to provide for a federally sanctioned self-determination process for the people of Puerto Rico.

Congress enacted major amendments to the Voting Rights Act of 1965 in 1970, 1975, 1982, 1992, and 2006. Each of these amendments coincided with an impending expiration of some of the Act's special provisions, which originally were set to expire by 1970. However, in recognition of the voting discrimination that continued despite the Act, Congress repeatedly amended the Act to reauthorize the special provisions.

The Stop Advertising Victims of Exploitation Act of 2014 is a bill that would prohibit knowingly benefitting financially from, receiving anything of value from, or distributing advertising that offers a commercial sex act in a manner that violates federal criminal code prohibitions against sex trafficking of children or of any person by force, fraud, or coercion. The bill would make it a felony to post prostitution ads online.

The Hmong Veterans' Naturalization Act of 2000 is &Se legislation which granted Hmong and ethnic Laotian veterans, who were legal refugee aliens in the US from the communist Lao government, and who also served in U.S.-backed guerrilla, or US special forces-backed units in Laos, during the Vietnam War, "an exemption from the English language requirement and special consideration for civics testing for certain refugees from Laos applying for naturalization." The initial Act gave these alien veterans eighteen months since the day of the bill's passage by the U.S. Congress, and its signature by the President of the United States, to file a naturalization application for honorary U.S. citizenship. However, the Act was later amended by additional legislation passed by the United States Congress which extended the N-400 filing date by an additional 18 months.

The New Way Forward Act is a proposed legislation introduced in the U.S. Senate and House on December 10, 2019 by Jesús "Chuy" García, which focuses on immigration reform. The bill would repeal sections 1325 and 1326 of the immigration law to decriminalize unauthorized border crossing whilst maintaining civil deportation procedures. The bill intends to give immigration judges discretion when deciding immigration claims for immigrants with criminal records in the United States, changes immigration enforcement by ending mandatory detention in specific cases and intends to remove private detention centers for immigrants.

The Fairness for High Skilled Immigrants Act is proposed United States federal legislation that would reform U.S. immigration policy, primarily by removing per-country limitations on employment-based visas, increasing the per-country numerical limitation for family-sponsored immigrants, and for other purposes. In 2020, for the first time it passed by House and Senate; however, the House and Senate versions were different and required reconciliation, and that reconciliation could not be carried out before the expiration of the 116th Congress. In order for the proposed legislation to further progress, it would have to be reintroduced into the 117th Congress and pass the House and Senate again.