In traditional Japanese aesthetics, wabi-sabi (侘び寂び) is a world view centered on the acceptance of transience and imperfection. The aesthetic is sometimes described as one of appreciating beauty that is "imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete" in nature. It is prevalent in many forms of Japanese art.

Tea ceremony is a ritualized practice of making and serving tea in East Asia practiced in the Sinosphere. The original term from China, literally translated as either "way of tea", "etiquette for tea or tea rite", or "art of tea" among the languages in the Sinosphere, is a cultural activity involving the ceremonial preparation and presentation of tea. Korean, Vietnamese and Japanese tea culture were inspired by the Chinese tea culture during ancient and medieval times, particularly after the successful transplant of the tea plant from Tang China to Korea, Vietnam and Japan by traveling Buddhist monks and scholars in 8th century and onwards.

Budai is a nickname given to the ancient Chinese monk Qici who is often identified with and venerated as Maitreya Buddha in Chan Buddhism. With the spread of Chan Buddhism, he also came to be venerated in Vietnam, Korea, and Japan. He is said to have lived around the 10th century CE in the Wuyue kingdom.

Buddhist symbolism is the use of symbols to represent certain aspects of the Buddha's Dharma (teaching). Early Buddhist symbols which remain important today include the Dharma wheel, the Indian lotus, the three jewels and the Bodhi tree.

Sesshū Tōyō, also known simply as Sesshū (雪舟), was a Japanese Zen monk and painter who is considered a great master of Japanese ink painting. Initially inspired by Chinese landscapes, Sesshū's work holds a distinctively Japanese style that reflects Zen Buddhist aesthetics. His prominent work captured images of landscapes, portraits, and birds and flowers paintings, infused with Zen Buddhist beliefs, flattened perspective, and emphatic lines.

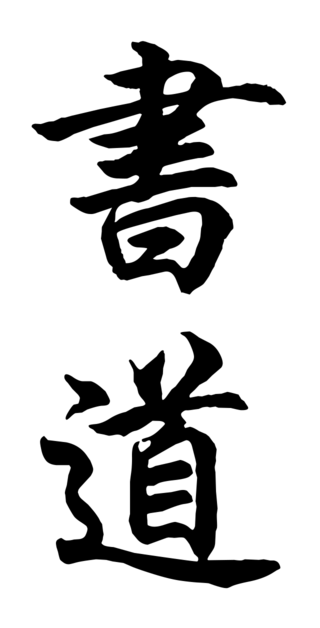

Japanese calligraphy, also called shūji (習字), is a form of calligraphy, or artistic writing, of the Japanese language. Written Japanese was originally based on Chinese characters only, but the advent of the hiragana and katakana Japanese syllabaries resulted in intrinsically Japanese calligraphy styles.

Hakuin Ekaku was one of the most influential figures in Japanese Zen Buddhism, who regarded bodhicitta, working for the benefit of others, as the ultimate concern of Zen-training. While never having received formal dharma transmission, he is regarded as the reviver of the Japanese Rinzai school from a period of stagnation, focusing on rigorous training methods integrating meditation and koan practice.

The Rinzai school ,named after Linji Yixuan is one of three sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism, along with Sōtō and Ōbaku. The Chinese Linji school of Chan Buddhism was first transmitted to Japan by Myōan Eisai. Contemporary Japanese Rinzai is derived entirely from the Ōtōkan lineage transmitted through Hakuin Ekaku (1686–1769), who is a major figure in the revival of the Rinzai tradition.

Haiga is a style of Japanese painting that incorporates the aesthetics of haikai. Haiga are typically painted by haiku poets (haijin), and often accompanied by a haiku poem. Like the poetic form it accompanied, haiga was based on simple, yet often profound, observations of the everyday world. Stephen Addiss points out that "since they are both created with the same brush and ink, adding an image to a haiku poem was ... a natural activity."

Japanese aesthetics comprise a set of ancient ideals that include wabi, sabi, and yūgen. These ideals, and others, underpin much of Japanese cultural and aesthetic norms on what is considered tasteful or beautiful. Thus, while seen as a philosophy in Western societies, the concept of aesthetics in Japan is seen as an integral part of daily life. Japanese aesthetics now encompass a variety of ideals; some of these are traditional while others are modern and sometimes influenced by other cultures.

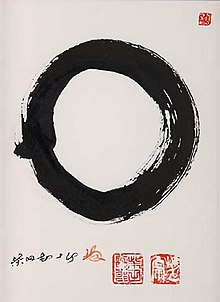

Sengai Gibon was a Japanese monk of the Rinzai school. He was known for his controversial teachings and writings, as well as for his lighthearted sumi-e paintings. After spending half of his life in Nagata near Yokohama, he secluded himself in Shōfuku-ji in Fukuoka, the first Zen temple in Japan, where he spent the rest of his life.

Zenga 禅画 is a term for the practice and art of Zen Buddhist painting and calligraphy in the Japanese tea ceremony and also the martial arts.

Kazuaki Tanahashi is an accomplished Japanese calligrapher, Zen teacher, author and translator of Buddhist texts from Japanese and Chinese to English, most notably works by Dogen. He first met Shunryu Suzuki in 1964, and upon reading Suzuki's book Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind he stated, "I could see it's Shobogenzo in a very plain, simple language." He has helped notable Zen teachers author books on Zen Buddhism, such as John Daido Loori. A fellow of the World Academy of Art and Science—Tanahashi is also an environmentalist and peaceworker.

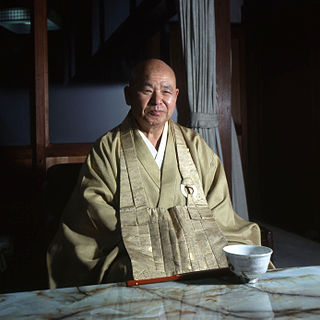

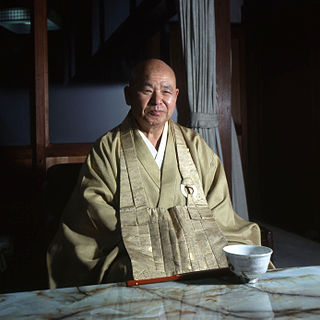

Keidō Fukushima was a Japanese Rinzai Zen master, head abbot of Tōfuku-ji, centered in Kyoto, Japan. Because of openness to teaching Western students, he had considerable influence on the development of Rinzai Zen practice in the West.

Buddhism played an important role in the development of Japanese art between the 6th and the 16th centuries. Buddhist art and Buddhist religious thought came to Japan from China through Korea. Buddhist art was encouraged by Crown Prince Shōtoku in the Suiko period in the sixth century, and by Emperor Shōmu in the Nara period in the eighth century. In the early Heian period, Buddhist art and architecture greatly influenced the traditional Shinto arts, and Buddhist painting became fashionable among wealthy Japanese. The Kamakura period saw a flowering of Japanese Buddhist sculpture, whose origins are in the works of Heian period sculptor Jōchō. During this period, outstanding busshi appeared one after another in the Kei school, and Unkei, Kaikei, and Tankei were especially famous. The Amida sect of Buddhism provided the basis for many popular artworks. Buddhist art became popular among the masses via scroll paintings, paintings used in worship and paintings of Buddhas, saint's lives, hells and other religious themes. Under the Zen sect of Buddhism, portraiture of priests such as Bodhidharma became popular as well as scroll calligraphy and sumi-e brush painting.

Nakahara Nantenbō, also known as Tōjū Zenchū, Tōshū Zenchū 鄧州全忠, and as Nantenbō Tōjū, was a Japanese Zen Master. In his time known as a fiery reformer, he was also a prolific and accomplished artist. He produced many fine examples of Zen Art and helped bridge the gap between older forms of Zen Buddhist art and its continuation in the 20th century.

Maxwell Harold Gimblett, is a New Zealand and American artist. His work, a harmonious postwar synthesis of American and Japanese art, brings together abstract expressionism, modernism, spiritual abstraction, and Zen calligraphy. Gimblett’s work was included in the exhibition The Third Mind: American Artists Contemplate Asia, 1869-1989 at the Guggenheim Museum and is represented in that museum's collection as well as thee collections of the Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of Art, National Gallery of Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, and the Auckland Art Gallery Toi O Tamaki, among others. Throughout the year Gimblett leads sumi ink workshops all over the world. In 2006 he was appointed Inaugural Visiting Professor at the National Institute of Creative Arts and Industries, Auckland University. Gimblett has received honorary doctorates from Waikato University and the Auckland University of Technology and was awarded the Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit (ONZM). He lives and works in New York and has returned to New Zealand over 65 times.

Awataguchi Takamitsu was a Japanese painter during the Muromachi (Ashikaga) period of Japanese history. He helped produce the Yūzū nembutsu engi (融通念仏縁起絵) housed in the Seiryō-ji, a Buddhist temple in Kyoto, Japan. He followed the Yamato-e school. Most of the works he produced were based and inspired by his Buddhist beliefs. He was also a court painter who painted five volumes of the Ashibiki-e scroll paintings during the Ōei period.

Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism that originated in China during the Tang dynasty as the Chan School or the Buddha-mind school, and later developed into various sub-schools and branches. From China, Chán spread south to Vietnam and became Vietnamese Thiền, northeast to Korea to become Seon Buddhism, and east to Japan, becoming Japanese Zen.

A water-dropper is a small device used in East Asian calligraphy as a container designed to hold a small amount of water. In order to make ink a few drops of water are dropped onto the surface of an inkstone. By grinding an inkstick into this water on the inkstone, particles come off and mix with the water, forming ink.