The alveolates are a group of protists, considered a major clade and superphylum within Eukarya, and are also called Alveolata.

Perkinsus marinus is a species of alveolates belonging to the phylum Perkinsozoa. It is similar to a dinoflagellate. It is known as a prevalent pathogen of oysters, causing massive mortality in oyster populations. The disease it causes is known as dermo or perkinsosis, and is characterized by the degradation of oyster tissues. The genome of this species has been sequenced.

Velvet disease is a fish disease caused by dinoflagellate parasites of the genus Piscinoodinium, specifically Amyloodinium in marine fish, and Oodinium in freshwater fish. The disease gives infected organisms a dusty, brownish-gold color. The disease occurs most commonly in tropical fish, and to a lesser extent, marine aquaria.

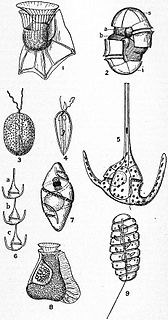

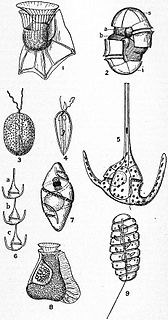

Retortamonas is a genus of flagellated excavates. It is one of only two genera belonging to the family Retortamonadidae along with the genus Chilomastix.

Noctiluca scintillans is a marine species of dinoflagellate that can exist in a green or red form, depending on the pigmentation in its vacuoles. It can be found worldwide, but its geographical distribution varies depending on whether it is green or red. This unicellular microorganism is known for its ability to bioluminesce, giving the water a bright blue glow seen at night. However, blooms of this species can be responsible for environmental hazards, such as toxic red tides. They may also be an indicator of anthropogenic eutrophication.

The Syndiniales are an order of early branching dinoflagellates, found as parasites of crustaceans, fish, algae, cnidarians, and protists. The trophic form is often multinucleate, and ultimately divides to form motile spores, which have two flagella in typical dinoflagellate arrangement. They lack a theca and chloroplasts, and unlike all other orders, the nucleus is never a dinokaryon. A well-studied example is Amoebophrya, which is a parasite of other dinoflagellates and may play a part in ending red tides. Several MALV groups have been assigned to Syndiniales; recent studies, however, show paraphyly of MALVs suggesting that only those groups that branch as sister to dinokaryotes belong to Syndiniales.

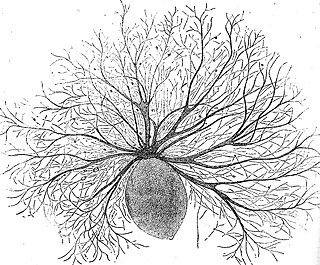

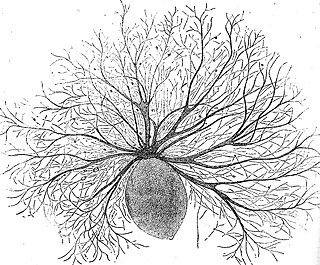

Trichonympha is a genus of single-celled, anaerobic parabasalids of the order Hypermastigia that is found exclusively in the hindgut of lower termites and wood roaches. Trichonympha’s bell shape and thousands of flagella make it an easily recognizable cell. The symbiosis between lower termites/wood roaches and Trichonympha is highly beneficial to both parties: Trichonympha helps its host digest cellulose and in return receives a constant supply of food and shelter. Trichonympha also has a variety of bacterial symbionts that are involved in sugar metabolism and nitrogen fixation.

Colpodella is a genus of alveolates comprising 5 species, and two further possible species: They share all the synapomorphies of apicomplexans, but are free-living, rather than parasitic. Many members of this genus were previously assigned to a different genus - Spiromonas.

The ciliates are a group of protozoans characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a different undulating pattern than flagella. Cilia occur in all members of the group and are variously used in swimming, crawling, attachment, feeding, and sensation.

Syndinium is a cosmopolitan genus of parasitic dinoflagellates that infest and kill marine planktonic species of copepods and radiolarians. Syndinium belongs to order Syndiniales, a candidate for the uncultured group I and II marine alveolates. The lifecycle of Syndinium is not well understood beyond the parasitic and zoospore stages.

Amoebophyra is a genus of dinoflagellates. Amoebophyra is a syndinian parasite that infects free-living dinoflagellates that are attributed to a single species by using several host-specific parasites. It acts as "biological control agents for red tides and in defining species of Amoebophrya." Researchers have found a correlation between a large amount of host specify and the impact host parasites may have on other organisms. Due to the host specificity found in each strain of Amoebophrya's physical makeup, further studies need to be tested to determine whether the Amoebophrya can act as a control against harmful algal blooms.

Rozella is a fungal genus of obligate endoparasites of a variety of hosts, including Oomycota, Chytridiomycota, and Blastocladiomycota. Rozella was circumscribed by French mycologist Marie Maxime Cornu in 1872. Considered one of the earliest diverging lineages of fungi, the widespread genus contains 27 species, with the most well studied being Rozella allomycis. Rozella is a member of a large clade of fungi referred to as the Cryptomycota/Rozellomycota. While some can be maintained in dual culture with the host, most have not been cultured, but they have been detected, using molecular techniques, in soil samples, and in freshwater and marine ecosystems. Zoospores have been observed, along with cysts, and the cells of some species are attached to diatoms.

Voromonas is a genus of predatory alveolates. The genus and species were described by Mylnikov in 2000. It was originally described as Colpodella pontica but was later renamed by Cavalier-Smith and Chao in 2004.

Ellobiopsis is a genus of unicellular, ectoparasitic eukaryotes causing disease in crustaceans. This genus is widespread and has been found infecting copepods from both marine and freshwater ecosystems. parasitism has been seen to interfere with fertility in both sexes of copepods.

Parvilucifera is a genus of marine alveolates that parasitise dinoflagellates. Parvilucifera is a parasitic genus described in 1999 by Norén et al. It is classified perkinsozoa in the supraphylum of Alveolates. This taxon serves as a sister taxon to the dinoflagellates and apicomplexans. Thus far, five species have been described in this taxon, which include: P.infectans, P.sinerae, P.corolla, P.rostrata, and P.prorocentri. The genus Parvilucifera is morphologically characterized by flagellated zoospore. The life cycle of the species in this genus consist of free-living zoospores, an intracellular stage called trophont, and asexual division to form resting sporangium inside host cell. This taxon has gained more interest in research due to its potential significance in terms of negative regulation for dinoflagellates blooms, that have proved harmful for algal species, humans, and the shellfish industry.

Chilomastix is a genus of pyriform excavates within the family Retortamonadidae All species within this genus are flagellated, structured with three flagella pointing anteriorly and a fourth contained within the feeding groove. Chilomastix also lacks Golgi apparatus and mitochondria but does possess a single nucleus. The genus parasitizes a wide range of vertebrate hosts, but is known to be typically non-pathogenic, and is therefore classified as harmless. The life cycle of Chilomastix lacks an intermediate host or vector. Chilomastix has a resistant cyst stage responsible for transmission and a trophozoite stage, which is recognized as the feeding stage. Chilomastix mesnili is one of the more studied species in this genus due to the fact it is a human parasite. Therefore, much of the information on this genus is based on what is known about this one species.

Dinoflagellates are eukaryotic plankton, existing in marine and freshwater environments. Previously, dinoflagellates had been grouped into two categories, phagotrophs and phototrophs. Mixotrophs, however include a combination of phagotrophy and phototrophy. Mixotrophic dinoflagellates are a sub-type of planktonic dinoflagellates and are part of the phylum Dinoflagellata. They are flagellated eukaryotes that combine photoautotrophy when light is available, and heterotrophy via phagocytosis. Dinoflagellates are one of the most diverse and numerous species of phytoplankton, second to diatoms.

Coccidinium is a genus of parasitic syndinian dinoflagellates that infect the nucleus and cytoplasm of other marine dinoflagellates. Coccidinium, along with two other dinoflagellate genera, Amoebophyra and Duboscquella, contain species that are the primary endoparasites of marine dinoflagellates. While numerous studies have been conducted on the genus Amoebophyra, specifically Amoebophyra ceratii, little is known about Coccidinium. These microscopic organisms have gone relatively unstudied after the initial observations of Édouard Chatton and Berthe Biecheler in 1934 and 1936.

Ichthyodinium is a monotypic genus of dinoflagellates in the family Dinophysaceae. Ichthyodinium chabelardi (/ɪkθioʊˈdɪniəm/) is currently the sole described species of the genus.

Haplozoon (/hæploʊ’zoʊən/) are unicellular endo-parasites, primarily infecting maldanid polychaetes. They belong to Dinoflagellata but differ from typical dinoflagellates. Most dinoflagellates are free-living and possess two flagella. Instead, Haplozoon belong to a 5% minority of parasitic dinoflagellates that are not free-living. Additionally, the Haplozoon trophont stage is particularly unique due to an apparent lack of flagella. The presence of flagella or remnant structures is the subject of ongoing research.