The French law on secularity and conspicuous religious symbols in schools bans wearing conspicuous religious symbols in French public primary and secondary schools. The law is an amendment to the French Code of Education that expands principles founded in existing French law, especially the constitutional requirement of laïcité: the separation of state and religious activities.

A dress code is a set of rules, often written, with regard to what clothing groups of people must wear. Dress codes are created out of social perceptions and norms, and vary based on purpose, circumstances, and occasions. Different societies and cultures are likely to have different dress codes, Western dress codes being a prominent example.

The Christian Institute (CI) is a charity operating in the United Kingdom, promoting a conservative evangelical Christian viewpoint, founded on a belief in Biblical inerrancy. The CI is a registered charity. The group does not report numbers of staff, volunteers or members with only the former director, Colin Hart, listed as a representative. Hart died in March 2024, leaving the directorship vacant. According to the accounts and trustees annual report for the financial year ending 2017, the average head count of employees during the year was 48 (2016:46).

The right to freedom of religion in the United Kingdom is provided for in all three constituent legal systems, by devolved, national, European, and international law and treaty. Four constituent nations compose the United Kingdom, resulting in an inconsistent religious character, and there is no state church for the whole kingdom.

Freedom of religion in Canada is a constitutionally protected right, allowing believers the freedom to assemble and worship without limitation or interference.

Sir Patrick Elias, PC, is a retired Lord Justice of Appeal.

Hijab and burka controversies in Europe revolve around the variety of headdresses worn by Muslim women, which have become prominent symbols of the presence of Islam in especially Western Europe. In several countries, the adherence to hijab has led to political controversies and proposals for a legal partial or full ban in some or all circumstances. Some countries already have laws banning the wearing of masks in public, which can be applied to veils that conceal the face. Other countries are debating similar legislation, or have more limited prohibitions. Some of them apply only to face-covering clothing such as the burqa, boushiya, or niqab; some apply to any clothing with an Islamic religious symbolism such as the khimar, a type of headscarf. The issue has different names in different countries, and "the veil" or hijab may be used as general terms for the debate, representing more than just the veil itself, or the concept of modesty embodied in Hijab.

R v Millais School Governing Body [2007] EWHC 1698 (Admin) is an English discrimination law case concerning freedom of religion. It was decided under the Human Rights Act 1998.

Redfearn v Serco Ltd [2006] EWCA Civ 659 and Redfearn v United Kingdom [2012] ECHR 1878 is a UK labour law and European Court of Human Rights case. It held that UK law was deficient in not allowing a potential claim based on discrimination for one's political belief. Before the case was decided, the Equality Act 2010 provided a remedy to protect political beliefs, though it had not come into effect when this case was brought.

The British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal is a quasi-judicial human rights body in British Columbia, Canada. It was established under British Columbia's Human Rights Code. It is responsible for "accepting, screening, mediating and adjudicating human rights complaints."

The Christian Legal Centre (CLC), a company founded in December 2007, has acted in a number of high-profile cases on behalf of evangelical Christians in the United Kingdom. Its sister organisation is Christian Concern. Observers believe that the centre has adopted tactics from wealthy evangelical groups in the US, notably the Alliance Defense Fund, and raise questions about its funding. It opposes homosexuality, same-sex marriage, pre-marital sex, and pornography.

Leyla Şahin v. Turkey was a 2004 European Court of Human Rights case brought against Turkey by a medical student challenging a Turkish law which bans wearing the Islamic headscarf at universities and other educational and state institutions. The Court upheld the Turkish law by 16 votes to 1.

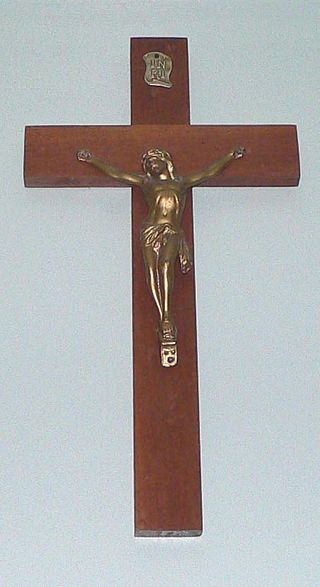

Lautsi v. Italy was a case brought before the European Court of Human Rights, which, on 18 March 2011, ruled that the requirement in Italian law that crucifixes be displayed in classrooms of schools does not violate the European Convention on Human Rights.

McFarlane v Relate Avon Ltd[2010] EWCA Civ 880; [2010] IRLR 872; 29 BHRC 249 was an application in the Court of Appeal of England and Wales for permission to appeal against a decision of the Employment Appeal Tribunal, that a relationship counsellor dismissed for refusing to counsel same sex couples on sexual matters because of his Christian beliefs did not suffer discrimination under the Employment Equality Regulations 2003. The application was heard by Lord Justice Laws, who issued his decision on 29 April 2010 refusing the application.

Azmi v Kirklees Metropolitan Borough Council [2007] IRLR 434 is a UK labour law case, concerning indirect discrimination on grounds of religion. The United Kingdom Employment Appeals Tribunal in London (EAT) dismissed the appeal in respect of discrimination and/or harassment, but awarded £1,100 to the plaintiff for victimisation, uprated by 10% as a result of the LEA's having failed to follow the statutory grievance protocol.

A ban on sharia law is legislation that prohibits the application or implementation of Islamic law (Sharia) in courts in any civil (non-religious) jurisdiction. In the United States for example, various states have "banned Sharia law," or a ballot measure was passed that "prohibits the state’s courts from considering foreign, international or religious law." As of 2014, these include Alabama, Arizona, Kansas, Louisiana, North Carolina, South Dakota and Tennessee. In the Canadian province of Ontario, family law disputes are arbitrated only under Ontario law.

British Airways plc v Williams (2011) C-155/10 is a UK labour law and EU law decision by the European Court of Justice regarding the right to holidays with pay, which is found in the Universal Declaration on Human Rights article 24, the Working Time Directive and the Working Time Regulations 1998. Williams itself was decided under analogous rules found in the Civil Aviation Regulations 2004. It held that variable components in pay, such as bonuses, must be included in the amount of pay people receive while they are on holiday.

Ladele v London Borough of Islington [2009] EWCA Civ 1357 is a UK labour law case concerning discrimination against same sex couples by a religious person in a public office.

A cross necklace is any necklace featuring a Christian cross or crucifix.

Lee v Ashers Baking Company Ltd and others[2018] UKSC 49 was a Supreme Court of the United Kingdom discrimination case between Gareth Lee and Ashers Baking Company, owned by Daniel and Amy McArthur of Northern Ireland. Lee brought the case after Ashers refused to make a cake with a message promoting same-sex marriage, citing their religious beliefs. Following appeals, the Supreme Court overturned previous rulings in favour of Lee and made a judgement in favour of Ashers. The court said there was no discrimination against Lee and that Ashers' objections were with the message they were being asked to promote. The court held that people in the United Kingdom could not legally be forced to promote a message they fundamentally disagreed with. The case became known in the British and Irish media as the "gay cake" case.