Related Research Articles

A riddle is a statement, question or phrase having a double or veiled meaning, put forth as a puzzle to be solved. Riddles are of two types: enigmas, which are problems generally expressed in metaphorical or allegorical language that require ingenuity and careful thinking for their solution, and conundra, which are questions relying for their effects on punning in either the question or the answer.

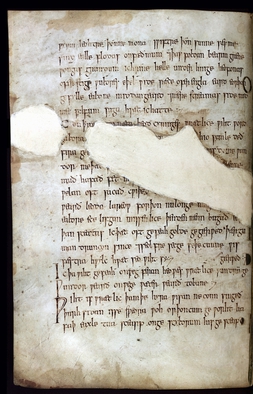

The Exeter Book, also known as the Codex Exoniensis or Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3501, is a large codex of Old English poetry, believed to have been produced in the late tenth century AD. It is one of the four major manuscripts of Old English poetry, along with the Vercelli Book in Vercelli, Italy, the Nowell Codex in the British Library, and the Junius manuscript in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. The book was donated to what is now the Exeter Cathedral library by Leofric, the first bishop of Exeter, in 1072. It is believed originally to have contained 130 or 131 leaves, of which the first 7 or 8 have been replaced with other leaves; the original first 8 leaves are lost. The Exeter Book is the largest and perhaps oldest known manuscript of Old English literature, containing about a sixth of the Old English poetry that has survived.

"The Husband's Message" is an anonymous Old English poem, 53 lines long and found only on folio 123 of the Exeter Book. The poem is cast as the private address of an unknown first-person speaker to a wife, challenging the reader to discover the speaker's identity and the nature of the conversation, the mystery of which is enhanced by a burn-hole at the beginning of the poem.

Anglo-Saxon riddles are a significant genre of Anglo-Saxon literature. The riddle was a major, prestigious literary form in early medieval England, and riddles were written both in Latin and Old English verse. The pre-eminent composer of Latin riddles in early medieval England was Aldhelm, while the Old English verse riddles found in the tenth-century Exeter Book include some of the most famous Old English poems.

Exeter Book Riddle 83 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Its interpretation has occasioned a range of scholarly investigations, but it is taken to mean 'Ore/Gold/Metal', with most commentators preferring 'precious metal' or 'gold', and John D. Niles arguing specifically for the Old English solution ōra, meaning both 'ore' and 'a kind of silver coin'.

Exeter Book Riddles 68 and 69 are two of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Their interpretation has occasioned a range of scholarly investigations, but clearly has something to do with ice and one or both of the riddles are likely indeed to have the solution "ice".

Exeter Book Riddle 60 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. The riddle is usually solved as 'reed pen', although such pens were not in use in Anglo-Saxon times, rather being Roman technology; but it can also be understood as 'reed pipe'.

Exeter Book Riddle 27 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. The riddle is almost universally solved as 'mead'.

Exeter Book Riddle 47 is one of the most famous of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Its solution is 'book-worm' or 'moth'.

The Exeter Book riddles are a fragmentary collection of verse riddles in Old English found in the later tenth-century anthology of Old English poetry known as the Exeter Book. Today standing at around ninety-four, the Exeter Book riddles account for almost all the riddles attested in Old English, and a major component of the otherwise mostly Latin corpus of riddles from early medieval England.

Exeter Book Riddle 30 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Since the suggestion of F. A. Blackburn in 1901, its solution has been agreed to be the Old English word bēam, understood both in its primary sense 'tree' but also in its secondary sense 'cross'.

Exeter Book Riddle 24 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. The riddle is one of a number to include runes as clues: they spell an anagram of the Old English word higoræ 'jay, magpie'. There has, therefore, been little debate about the solution.

The writing-riddle is an international riddle type, attested across Europe and Asia. Its most basic form was defined by Antti Aarne as 'white field, black seeds', where the field is a page and the seeds are letters. However, this form admits of variations very diverse in length and degree of detail. For example, a version from Astrakhan translates as "the enclosure is white, the sheep are black", while one from the Don Kalmyks appears as "a black dog runs on white snow", and literary riddlers especially have produced long variations on the theme, often overlapping with riddles on pens and other writing equipment.

Exeter Book Riddle 45 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Its solution is accepted to be 'dough'. However, the description evokes a penis becoming erect; as such, Riddle 45 is noted as one of a small group of Old English riddles that engage in sexual double entendre, and thus provides rare evidence for Anglo-Saxon attitudes to sexuality, and specifically for women taking the initiative in heterosexual sex.

Exeter Book Riddle 44 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Its solution is accepted to be 'key'. However, the description evokes a penis; as such, Riddle 44 is noted as one of a small group of Old English riddles that engage in sexual double entendre, and thus provides rare evidence for Anglo-Saxon attitudes to sexuality.

Exeter Book Riddle 25 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Suggested solutions have included Hemp, Leek, Onion, Rosehip, Mustard and Phallus, but the consensus is that the solution is Onion.

Exeter Book Riddle 33 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Its solution is accepted to be 'Iceberg'. The most extensive commentary on the riddle is by Corinne Dale, whose ecofeminist analysis of the riddles discusses how the iceberg is portrayed through metaphors of warrior violence but at the same time femininity.

Exeter Book Riddle 12 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Its solution is accepted to be 'ox/ox-hide'. The riddle has been described as 'rather a cause celebre in the realm of Old English poetic scholarship, thanks to the combination of its apparently sensational, and salacious, subject matter with critical issues of class, sex, and gender'. The riddle is also of interest because of its reference to an enslaved person, possibly ethnically British.

Exeter Book Riddle 7 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book, in this case on folio 103r. The solution is believed to be 'swan' and the riddle is noted as being one of the Old English riddles whose solution is most widely agreed on. The riddle can be understood in its manuscript context as part of a sequence of bird-riddles.

Exeter Book Riddle 26 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book.

References

- ↑ Dieter Bitterli, Say what I am Called: The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book and the Anglo-Latin Riddle Tradition, Toronto Anglo-Saxon Series, 2 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009), p.146.

- ↑ Helen Price, ‘Human and NonHuman in Anglo-Saxon and British Postwar Poetry: Reshaping Literary Ecology’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Leeds, 2014), p. 127.

- ↑ Helen Price, ‘Human and NonHuman in Anglo-Saxon and British Postwar Poetry: Reshaping Literary Ecology’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Leeds, 2014), p. 126.