Boniface, OSB was an English Benedictine monk and leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of Francia during the eighth century. He organised significant foundations of the church in Germany and was made bishop of Mainz by Pope Gregory III. He was martyred in Frisia in 754, along with 52 others, and his remains were returned to Fulda, where they rest in a sarcophagus which remains a site of Christian pilgrimage.

Aldhelm, Abbot of Malmesbury Abbey, Bishop of Sherborne, and a writer and scholar of Latin poetry, was born before the middle of the 7th century. He is said to have been the son of Kenten, who was of the royal house of Wessex. He was certainly not, as his early biographer Faritius asserts, the brother of King Ine. After his death he was venerated as a saint, his feast day being the day of his death, 25 May.

A riddle is a statement, question or phrase having a double or veiled meaning, put forth as a puzzle to be solved. Riddles are of two types: enigmas, which are problems generally expressed in metaphorical or allegorical language that require ingenuity and careful thinking for their solution, and conundra, which are questions relying for their effects on punning in either the question or the answer.

De Dubiis Nominibus is a 7th-century document, possibly from Bordeaux, by an anonymous author. It is an alphabetically sorted list of words whose gender, plural form or spelling was in question by the author. The author attempted to resolve the questions through citations from classical and Christian authors with notes next to each word.

Tatwine was the tenth Archbishop of Canterbury from 731 to 734. Prior to becoming archbishop, he was a monk and abbot of a Benedictine monastery. Besides his ecclesiastical career, Tatwine was a writer, and riddles he composed survive. Another work he composed was on the grammar of the Latin language, which was aimed at advanced students of that language. He was subsequently considered a saint.

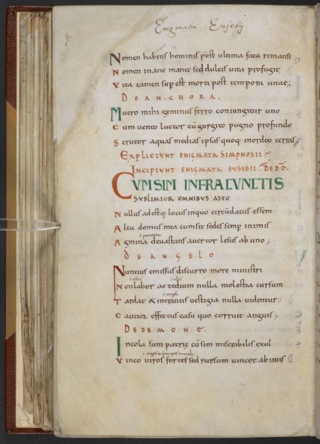

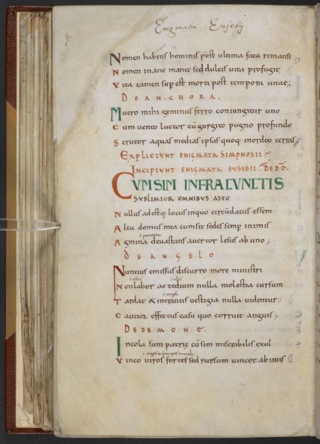

Symphosius was the author of the Aenigmata, an influential collection of 100 Latin riddles, probably from the late antique period. They have been transmitted along with their solutions.

Anglo-Saxon riddles are a significant genre of Anglo-Saxon literature. The riddle was a major, prestigious literary form in early medieval England, and riddles were written both in Latin and Old English verse. The pre-eminent composer of Latin riddles in early medieval England was Aldhelm, while the Old English verse riddles found in the tenth-century Exeter Book include some of the most famous Old English poems.

The "Leiden Riddle" is an Old English riddle. It is noteworthy for being one of the earliest attested pieces of English poetry; one of only a small number of representatives of the Northumbrian dialect of Old English; one of only a relatively small number of Old English poems to survive in multiple manuscripts; and evidence for the translation of the Latin poetry of Aldhelm into Old English.

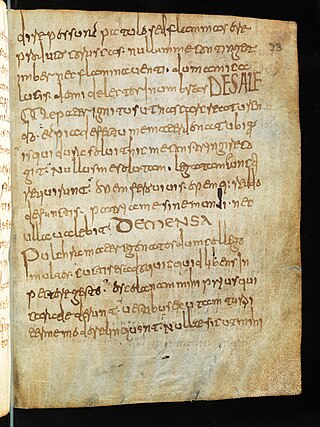

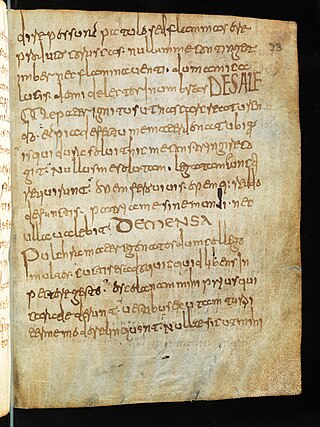

The Bern Riddles, also known as Aenigmata Bernensia, Aenigmata Hexasticha or Riddles of Tullius, are a collection of 63 metrical Latin riddles, named after the location of their earliest surviving manuscript, which today is held in Bern : the early eighth-century Codex Bernensis 611.

The Lorsch riddles, also known as the Aenigmata Anglica, are a collection of twelve hexametrical, early medieval Latin riddles that were anonymously written in the ninth century.

Exeter Book Riddle 83 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Its interpretation has occasioned a range of scholarly investigations, but it is taken to mean 'Ore/Gold/Metal', with most commentators preferring 'precious metal' or 'gold', and John D. Niles arguing specifically for the Old English solution ōra, meaning both 'ore' and 'a kind of silver coin'.

Exeter Book Riddle 60 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. The riddle is usually solved as 'reed pen', although such pens were not in use in Anglo-Saxon times, rather being Roman technology; but it can also be understood as 'reed pipe'.

The main Ancient Greek terms for riddle are αἴνιγμα and γρῖφος. The two terms are often used interchangeably, though some ancient commentators tried to distinguish between them.

De creatura is an 83-line Latin polystichic poem by the seventh- to eighth-century Anglo-Saxon poet Aldhelm and an important text among Anglo-Saxon riddles. The poem seeks to express the wondrous diversity of creation, usually by drawing vivid contrasts between different natural phenomena, one of which is usually physically higher and more magnificent, and one of which is usually physically lower and more mundane.

The featherless bird-riddle is an international riddle type that compares a snowflake to a bird. In the nineteenth century, it attracted considerable scholarly attention because it was seen as a possible reflex of ancient Germanic riddling, arising from magical incantations. Although the language of the riddle is reminiscent of European charms, later work, particularly by Antti Aarne, showed that it occurred widely throughout Europe─particularly central Europe─and that it is therefore an international riddle type. Archer Taylor concluded that 'the equating of a snowflake to a bird and the sun to a maiden without hands is an elementary idea that cannot yield much information about Germanic myth'.

Exeter Book Riddle 65 is one of the Old English riddles found in the later tenth-century Exeter Book. Suggested solutions have included Onion, Leek, and Chives, but the consensus is that the solution is Onion.

The Epistola ad Acircium, sive Liber de septenario, et de metris, aenigmatibus ac pedum regulis is a Latin treatise by the West-Saxon scholar Aldhelm. It is dedicated to one Acircius, understood to be King Aldfrith of Northumbria. It was a seminal text in the development of riddles as a literary form in medieval England.

The Enigmata Eusebii are a collection of sixty Latin, hexametrical riddles composed in early medieval England, probably in the eighth century.

The Liber epigrammatum is a collection of Latin epigrammatic poems composed by the Northumbrian monk Bede. The modern title comes from a list of his works at the end of his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (V.24.2): "librum epigrammatum heroico metro siue elegiaco".

Four Hang; Two Point the Way is the name given by the folklorist Archer Taylor to a traditional riddle-type noted for its wide international distribution. The most common solution is 'cow', and in Taylor's view 'we can probably infer that a cow was the original answer'.