External links

| | This Spanish history–related article is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |

| | This article about the military history of Ancient Rome is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |

Falarica, also Phalarica, was an ancient Iberian ranged polearm that was sometimes used as an incendiary weapon.

The Falarica was a heavy javelin with a long, thin iron head of about 900 mm (35 in) in length attached to a wooden shaft of about equal length. The iron head had a narrow sharp tip, which made the falarica an excellent armour-piercing weapon.

The Iberians used to bind combustible material to the metal shaft of the weapon and use the falarica as an incendiary projectile. The incendiary javelin would hit the shields or siege works of the enemy often setting them ablaze.

The falarica could also be launched by the use of spear throwers or siege engines to increase its range and velocity.

the besieged were protected and the enemy kept away from the gates by the falarica, which many arms at once were wont to poise... when hurled like a thunderbolt from the topmost walls of the citadel, it clove the furrowed air with a flickering flame, even as a fiery meteor speeding from heaven to earth dazzles men's eyes with its blood red tail... and when in flight it struck the side of a huge tower, it kindled a fire which burnt until all of the woodwork of the tower was utterly consumed. [1]

Falarica comes from either ancient Greek phalòs (φαλòς), because it came out of a phala (an ancient round tower posted on cities' walls and was used to fire the falaricas), or from phalēròs (φαληρòς) "shining" as it was enwrapped with blazing fire.

Although in some texts the term falarica is used as a poetic description for a Roman weapon, its origin seems to be from the Western Mediterranean and in most respects it was similar to the pre-Marian pilum. There are references to its use when the Iberians fought against the Carthaginian invasions. There are remains of falarica amongst Iberian and Celtiberian archaeological deposits from the 3rd century BC to the 1st century AD.

A sling is a projectile weapon typically used to hand-throw a blunt projectile such as a stone, clay, or lead "sling-bullet". It is also known as the shepherd's sling or slingshot. Someone who specializes in using slings is called a slinger.

A spear is a polearm consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fastened to the shaft, such as bone, flint, obsidian, copper, bronze, iron, or steel. The most common design for hunting and/or warfare, since ancient times has incorporated a metal spearhead shaped like a triangle, diamond, or leaf. The heads of fishing spears usually feature multiple sharp points, with or without barbs.

The ballista, plural ballistae, sometimes called bolt thrower, was an ancient missile weapon that launched either bolts or stones at a distant target.

The pilum was a javelin commonly used by the Roman army in ancient times. It was generally about 2 m long overall, consisting of an iron shank about 7 mm (0.28 in) in diameter and 600 mm (24 in) long with a pyramidal head, attached to a wooden shaft by either a socket or a flat tang.

The sarissa or sarisa was a long spear or pike about 5 to 7 meters in length. It was introduced by Philip II of Macedon and was used in his Macedonian phalanxes as a replacement for the earlier dory, which was considerably shorter. These longer spears improved the strength of the phalanx by extending the rows of overlapping weapons projecting towards the enemy. After the conquests of Alexander the Great, the sarissa was a mainstay during the Hellenistic era by the Hellenistic armies of the diadochi Greek successor states of Alexander's empire, as well as some of their rivals.

Early thermal weapons, which used heat or burning action to destroy or damage enemy personnel, fortifications or territories, were employed in warfare during the classical and medieval periods.

Roman siege engines were, for the most part, adapted from Hellenistic siege technology. Relatively small efforts were made to develop the technology; however, the Romans brought an unrelentingly aggressive style to siege warfare that brought them repeated success. Up to the first century BC, the Romans utilized siege weapons only as required and relied for the most part on ladders, towers and rams to assault a fortified town. Ballistae were also employed, but held no permanent place within a legion's roster, until later in the republic, and were used sparingly. Julius Caesar took great interest in the integration of advanced siege engines, organizing their use for optimal battlefield efficiency.

An assegai or assagai is a polearm used for throwing, usually a light spear or javelin made up of a wooden handle with an iron tip.

A spiculum is a late Roman spear that replaced the pilum as the infantryman's main throwing javelin around 250 AD. Scholars suppose that it could have resulted from the gradual combination of the pilum and two German spears, the angon and the bebra. As more and more Germans joined the Roman army, their culture and traditions became a driving force for change. The spiculum was better than the old pilum when used as a thrusting spear, but still maintained some of the former weapon's penetrative power when thrown.

The army of the Kingdom of Macedon was among the greatest military forces of the ancient world. It was created and made formidable by King Philip II of Macedon; previously the army of Macedon had been of little account in the politics of the Greek world, and Macedonia had been regarded as a second-rate power.

Soliferrum or Soliferreum was the Roman name for an ancient Iberian ranged polearm made entirely of iron. The soliferrum was a heavy hand-thrown javelin, designed to be thrown to a distance of up to 30 meters. In the Iberian language it was known as Saunion.

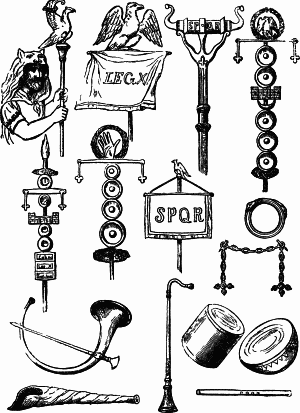

Roman military personal equipment was produced in large numbers to established patterns, and used in an established manner. These standard patterns and uses were called the res militaris or disciplina. Its regular practice during the Roman Republic and Roman Empire led to military excellence and victory. The equipment gave the Romans a very distinct advantage over their barbarian enemies, especially so in the case of armour. This does not mean that every Roman soldier had better equipment than the richer men among his opponents. Roman equipment was not of a better quality than that used by the majority of Rome's adversaries. Other historians and writers have stated that the Roman army's need for large quantities of "mass produced" equipment after the so-called "Marian Reforms" and subsequent civil wars led to a decline in the quality of Roman equipment compared to the earlier Republican era:

The production of these kinds of helmets of Italic tradition decreased in quality because of the demands of equipping huge armies, especially during civil wars...The bad quality of these helmets is recorded by the sources describing how sometimes they were covered by wicker protections, like those of Pompeius' soldiers during the siege of Dyrrachium in 48 BC, which were seriously damaged by the missiles of Caesar's slingers and archers.

It would appear that armour quality suffered at times when mass production methods were being used to meet the increased demand which was very high the reduced size cuirasses would also have been quicker and cheaper to produce, which may have been a deciding factor at times of financial crisis, or where large bodies of men were required to be mobilized at short notice, possibly reflected in the poor-quality, mass produced iron helmets of Imperial Italic type C, as found, for example, in the River Po at Cremona, associated with the Civil Wars of AD 69 AD; Russell Robinson, 1975, 67

Up until then, the quality of helmets had been fairly consistent and the bowls well decorated and finished. However, after the Marian Reforms, with their resultant influx of the poorest citizens into the army, there must inevitably have been a massive demand for cheaper equipment, a situation which can only have been exacerbated by the Civil Wars...

A javelin is a light spear designed primarily to be thrown, historically as a ranged weapon. Today, the javelin is predominantly used for sporting purposes such as the Javelin throw. The javelin is nearly always thrown by hand, unlike the sling, bow, and crossbow, which launch projectiles with the aid of a hand-held mechanism. However, devices do exist to assist the javelin thrower in achieving greater distances, such as spear-throwers or the amentum.

The verutum, plural veruta, was a short javelin used in the Roman army. This javelin was used by the velites for skirmishing purposes, unlike the heavier pilum, which was used by the hastati and principes for weakening the enemy before advancing into close combat. The shafts were about 1.1 metres long, substantially shorter than the 2-metre pilum, and the point measured about 13 centimetres (5 in) long. The verutum had either an iron shank like the pilum or a tapering metal head. It was sometimes thrown with the aid of a throwing strap, or amentum.

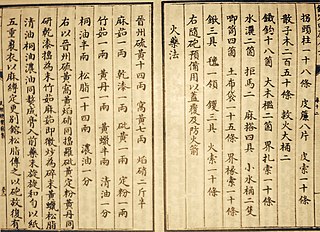

The Wujing Zongyao, sometimes rendered in English as the Complete Essentials for the Military Classics, is a Chinese military compendium written from around 1040 to 1044.

The angon was a type of javelin used during the Early Middle Ages by the Anglo-Saxons, Franks, Goths, and other Germanic peoples. It was similar to, and probably derived from, the pilum used by the Roman army and had a barbed head and long narrow socket or shank made of iron mounted on a wooden haft.

Major innovations in the history of weapons have included the adoption of different materials – from stone and wood to different metals, and modern synthetic materials such as plastics – and the developments of different weapon styles either to fit the terrain or to support or counteract different battlefield tactics and defensive equipment.

The Caetrati were a type of light infantry in ancient Iberia who often fought as skirmishers. They were armed with a caetra shield, swords, and javelins.

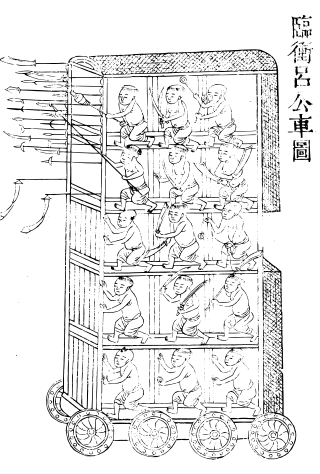

This is an overview of Chinese siege weapons.