In jurisprudence, double jeopardy is a procedural defence that prevents an accused person from being tried again on the same charges following an acquittal or conviction and in rare cases prosecutorial and/or judge misconduct in the same jurisdiction. Double jeopardy is a common concept in criminal law - in civil law, a similar concept is that of res judicata. The double jeopardy protection in criminal prosecutions only bars an identical prosecution for the same offense, however, a different offense may be charged on identical evidence at a second trial. Res judicata protection is stronger - it precludes any causes of action or claims that arise from a previously litigated subject matter.

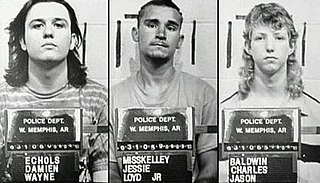

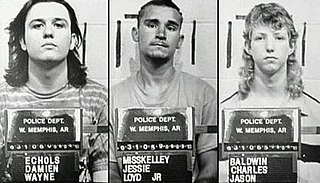

The West Memphis Three are three men convicted as teenagers in 1994 of the 1993 murders of three boys in West Memphis, Arkansas, United States. Damien Echols was sentenced to death, Jessie Misskelley Jr. to life imprisonment plus two 20-year sentences, and Jason Baldwin to life imprisonment. During the trial, the prosecution asserted that the juveniles killed the children as part of a Satanic ritual.

In jurisprudence, prosecutorial misconduct or prosecutorial overreach is "an illegal act or failing to act, on the part of a prosecutor, especially an attempt to sway the jury to wrongly convict a defendant or to impose a harsher than appropriate punishment." It is similar to selective prosecution. Prosecutors are bound by a sets of rules which outline fair and dispassionate conduct.

Circumstantial evidence is evidence that relies on an inference to connect it to a conclusion of fact—such as a fingerprint at the scene of a crime. By contrast, direct evidence supports the truth of an assertion directly—i.e., without need for any additional evidence or inference.

A miscarriage of justice occurs when an unfair outcome occurs in a criminal or civil proceeding, such as the conviction and punishment of a person for a crime they did not commit. Miscarriages are also known as wrongful convictions. Innocent people have sometimes ended up in prison for years before their conviction has eventually been overturned. They may be exonerated if new evidence comes to light or it is determined that the police or prosecutor committed some kind of misconduct at the original trial. In some jurisdictions this leads to the payment of compensation.

Mistaken identity is a defense in criminal law which claims the actual innocence of the criminal defendant, and attempts to undermine evidence of guilt by asserting that any eyewitness to the crime incorrectly thought that they saw the defendant, when in fact the person seen by the witness was someone else. The defendant may question both the memory of the witness, and the perception of the witness.

Within the criminal justice system of Japan, there exist three basic features that characterize its operations. First, the institutions—police, government prosecutors' offices, courts, and correctional organs—maintain close and cooperative relations with each other, consulting frequently on how best to accomplish the shared goals of limiting and controlling crime. Second, citizens are encouraged to assist in maintaining public order, and they participate extensively in crime prevention campaigns, apprehension of suspects, and offender rehabilitation programs. Finally, officials who administer criminal justice are allowed considerable discretion in dealing with offenders.

Actual innocence is a special standard of review in legal cases to prove that a charged defendant did not commit the crimes that they were accused of, which is often applied by appellate courts to prevent a miscarriage of justice.

The New York State Police Troop C scandal involved the fabrication of evidence by members of the New York State Police, which was used to convict suspects in Central New York.

The FBI Laboratory is a division within the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation that provides forensic analysis support services to the FBI, as well as to state and local law enforcement agencies free of charge. The lab is located at Marine Corps Base Quantico in Quantico, Virginia. Opened November 24, 1932, the lab was first known as the Technical Laboratory. It became a separate division when the original Bureau of Investigation (BOI) was renamed the FBI.

David Ray Camm is a former trooper of the Indiana State Police (ISP) who spent 13 years in prison after twice being wrongfully convicted of the murders of his wife, Kimberly, and his two young children at their home in Georgetown, Indiana, on September 28, 2000. He was released from custody in 2013 after his third trial resulted in an acquittal. Charles Boney is currently serving time for the murders of Camm's wife and two children.

The Norfolk Four are four former United States Navy sailors: Joseph J. Dick Jr., Derek Tice, Danial Williams, and Eric C. Wilson, who were wrongfully convicted of the 1997 rape and murder of Michelle Moore-Bosko while they were stationed at Naval Station Norfolk. They each declared that they had made false confessions, and their convictions are considered highly controversial. A fifth man, Omar Ballard, confessed and pleaded guilty to the crime in 2000, insisting that he had acted alone. He had been in prison since 1998 because of violent attacks on two other women in 1997. He was the only one of the suspects whose DNA matched that collected at the crime scene, and whose confession was consistent with other forensic evidence.

Amanda Marie Knox is an American author, activist, and journalist. She spent almost four years incarcerated in Italy following her wrongful conviction for the 2007 murder of Meredith Kercher, a fellow exchange student with whom she shared an apartment in Perugia. In 2015, Knox was definitively acquitted by the Italian Supreme Court of Cassation.

The Peggy Hettrick murder case concerns the unsolved 1987 death of Peggy Hettrick in Fort Collins, Colorado. Timothy Lee "Tim" Masters enlisted in the United States Navy following a high school career plagued by police accusation of murder when he was a sophomore at Fort Collins High School. After eight years in the Navy, he was honorably discharged. Masters worked for Learjet as an aviation mechanic until 1997, when he was arrested for the murder of Peggy Hettrick. He was charged and convicted of the Hettrick murder in 1999 and sentenced to life imprisonment without parole. His sentence was vacated in January 2008 when DNA evidence from the original crime scene indicated that he was not the responsible party. Three years after his release from prison, Masters was exonerated by the Colorado Attorney General on June 28, 2011. To date, no one else has been charged with Hettrick's murder.

Kyles v. Whitley, 514 U.S. 419 (1995), is a United States Supreme Court case that held that a prosecutor has an affirmative duty to disclose evidence favorable to a defendant pursuant to Brady v. Maryland and United States v. Bagley.

The Double Jeopardy Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution provides: "[N]or shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb..." The four essential protections included are prohibitions against, for the same offense:

Maryland v. King, 569 U.S. 435 (2013), was a decision of the United States Supreme Court which held that a cheek swab of an arrestee's DNA is comparable to fingerprinting and therefore, a legal police booking procedure that is reasonable under the Fourth Amendment.

Juan A. Rivera Jr. is an American man who was wrongfully convicted three times for the 1992 rape and murder of 11-year-old Holly Staker in Waukegan, Illinois. He was convicted twice on the basis of a confession that he said was coerced. No physical evidence linked him to the crime scene. In 2015 he received a $20 million settlement from Lake County, Illinois for wrongful conviction, formerly the largest settlement of its kind in United States history.

The murder of Tair Rada, a 13-year-old Israeli schoolgirl, was committed in 2006, in the girls' bathroom of her school in Katzrin. Roman Zdorov, a Ukrainian and a resident of Israel, was convicted of the murder and was sentenced to life imprisonment on September 14, 2010. His prosecution and conviction have been a source of controversy, receiving much media coverage, as well as being the focus of an Israeli documentary TV series called Shadow of Truth that has gained worldwide attention on Netflix. On August 26, 2021, Zadorov was released from prison to house arrest after many appeals.

Steven A. Drizin is an American lawyer and academic. He is a Clinical Professor of Law at the Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law in Chicago, where he has been on the faculty since 1991. At Northwestern, Drizin teaches courses on Wrongful Convictions and Juvenile Justice. He has written extensively on the topics of police interrogations and false confessions. Among the general public, Drizin is known for his ongoing representation of Brendan Dassey, one of the protagonists in the Netflix documentary series, Making a Murderer.