John Llewellyn Lewis was an American leader of organized labor who served as president of the United Mine Workers of America (UMW) from 1920 to 1960. A major player in the history of coal mining, he was the driving force behind the founding of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which established the United Steel Workers of America and helped organize millions of other industrial workers in the 1930s, during the Great Depression. After resigning as head of the CIO in 1941, Lewis took the United Mine Workers out of the CIO in 1942 and in 1944 took the union into the American Federation of Labor (AFL).

The United Mine Workers of America is a North American labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and public employees in the United States and Canada. Although its main focus has always been on workers and their rights, the UMW of today also advocates for better roads, schools, and universal health care. By 2014, coal mining had largely shifted to open pit mines in Wyoming, and there were only 60,000 active coal miners. The UMW was left with 35,000 members, of whom 20,000 were coal miners, chiefly in underground mines in Kentucky and West Virginia. However it was responsible for pensions and medical benefits for 40,000 retired miners, and for 50,000 spouses and dependents.

The history of coal mining goes back thousands of years, with early mines documented in ancient China, the Roman Empire and other early historical economies. It became important in the Industrial Revolution of the 19th and 20th centuries, when it was primarily used to power steam engines, heat buildings and generate electricity. Coal mining continues as an important economic activity today, but has begun to decline due to the strong contribution coal plays in global warming and environmental issues, which result in decreasing demand and in some geographies, peak coal.

The Coal strike of 1902 was a strike by the United Mine Workers of America in the anthracite coalfields of eastern Pennsylvania. Miners struck for higher wages, shorter workdays, and the recognition of their union. The strike threatened to shut down the winter fuel supply to major American cities. At that time, residences were typically heated with anthracite or "hard" coal, which produces higher heat value and less smoke than "soft" or bituminous coal.

The Lattimer massacre was the violent deaths of at least 19 unarmed striking immigrant anthracite miners at the Lattimer mine near Hazleton, Pennsylvania, United States, on September 10, 1897. The miners, mostly of Polish, Slovak, Lithuanian and German ethnicity, were shot and killed by a Luzerne County sheriff's posse. Scores more workers were wounded. The massacre was a turning point in the history of the United Mine Workers (UMW).

The Herrin massacre took place on June 21–22, 1922 in Herrin, Illinois, in a coal mining area during a nationwide strike by the United Mineworkers of America (UMWA). Although the owner of the mine originally agreed with the union to observe the strike, when the price of coal went up, he hired non-union workers to produce and ship out coal, as he had high debt in start-up costs.

The Harlan County War, or Bloody Harlan, was a series of coal industry skirmishes, executions, bombings and strikes that took place in Harlan County, Kentucky, during the 1930s. The incidents involved coal miners and union organizers on one side and coal firms and law enforcement officials on the other. The Harlan County coal miners campaigned and fought to organize their workplaces and better their wages and working conditions. It was a nearly decade-long conflict, lasting from 1931 to 1939. Before its conclusion, an unknown number of miners, deputies and bosses would be killed, state and federal troops would occupy the county more than half a dozen times, two acclaimed folk singers would emerge, union membership would oscillate wildly and workers in the nation's most anti-labor coal county would ultimately be represented by a union.

The Coal and Iron Police was a private police force in the US state of Pennsylvania that existed between 1865 and 1931. It was established by the Pennsylvania General Assembly but employed and paid by the various coal companies. The origins of the Coal and Iron Police begin in 1865. Law enforcement in Pennsylvania at that time existed only on the county level or below; an elected sheriff was the primary law enforcement officer. The case was made by the coal and iron operators that they required additional protection of their property. Thus the Pennsylvania State Legislature passed State Act 228. This empowered the railroads to organize private police forces. In 1866, a supplement to the act was passed extending the privilege to "embrace all corporations, firms, or individuals, owning, leasing, or being in possession of any colliery, furnace, or rolling mill within this commonwealth". The 1866 supplement also stipulated that the words "coal and iron police" appear on their badges. A total of over 7,632 commissions were given for the Coal and Iron Police.

The Paint Creek–Cabin Creek Strike, or the Paint Creek Mine War, was a confrontation between striking coal miners and coal operators in Kanawha County, West Virginia, centered on the area enclosed by two streams, Paint Creek and Cabin Creek.

The West Virginia coal wars (1912–1921), also known as the mine wars, arose out of a dispute between coal companies and miners.

The Hartford coal mine riot occurred on July 12, 1914, at Hartford, Arkansas. In a productive region of a state with 100% of its coal miners represented by the United Mine Workers (UMW), one mine owner attempted to open a non-union shop. In the resulting conflict, mines were flooded by sabotage, and on July 17 a crowd of union miners and sympathizers destroyed the surface plant of the Prairie Creek coal mine #3 and murdered two non-union miners.

The Bituminous coal strike of 1974 was a 28-day national coal strike in the United States led by the United Mine Workers of America, AFL–CIO. It is generally considered a successful strike by the union.

The Bituminous coal strike of 1977–1978 was a 110-day national coal strike in the United States led by the United Mine Workers of America, AFL–CIO. It began December 6, 1977, and ended on March 19, 1978. It is generally considered a successful union strike, although the contract was not beneficial to union members.

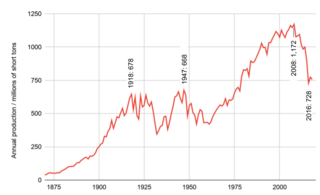

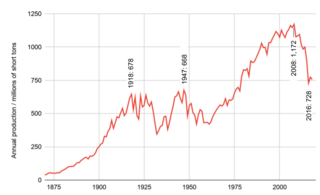

The history of coal mining in the United States goes back to the 1300s, when the Hopi Indians used coal. The first commercial use came in 1701, within the Manakin-Sabot area of Richmond, Virginia. Coal was the dominant power source in the United States in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and although in rapid decline it remains a significant source of energy in 2019.

The 1920 Alabama coal strike, or the Alabama miners' strike, was a statewide strike of the United Mine Workers of America against coal mine operators. The strike was marked by racial violence, and ended in significant defeat for the union and organized labor in Alabama.

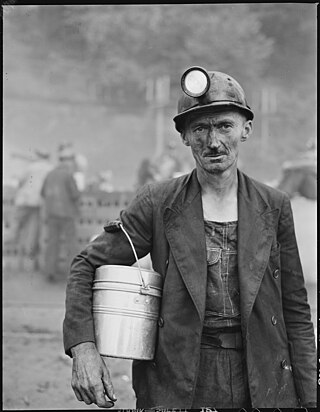

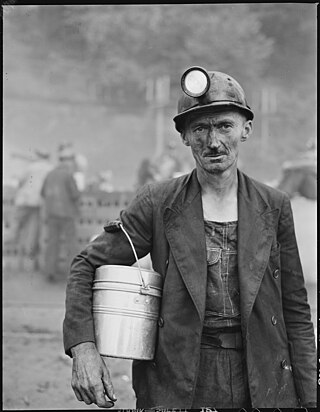

People have worked as coal miners for centuries, but they became increasingly important during the Industrial revolution when coal was burnt on a large scale to fuel stationary and locomotive engines and heat buildings. Owing to coal's strategic role as a primary fuel, coal miners have figured strongly in labor and political movements since that time.

The 1927 Indiana bituminous strike was a strike by members of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) against local bituminous coal companies. Although the struggle raged throughout most of the nation's coal fields, its most serious impact was in western Pennsylvania, including Indiana County. The strike began on April 1, 1927, when almost 200,000 coal miners struck the coal mining companies operating in the Central Competitive Field, after the two sides could not reach an agreement on pay rates. The UMWA was attempting to retain pay raises gained in the contracts it had negotiated in 1922 and 1924, while management, stating that it was under economic pressure from competition with the West Virginia coal mines, was seeking wage reductions. The strike proved to be a disaster for the union, as by 1929, there were only 84,000 paying members of the union, down from 400,000 which belonged to the union in 1920.

Warren G. Harding was inaugurated as the 29th president of the United States on March 4, 1921 and served as president until his death on August 2, 1923, 881 days later. During his presidency, Harding organized international disarmament agreements, addressed major labor disputes, enacted legislation and regulations pertaining to veterans' rights, and traveled west to visit Alaska.

The 1922 UMW Miner strike was a nationwide strike of miners in the US that occurred after a United Mine Workers (UMW) trade union contract expired on March 31, 1922. The strike was declared on April 1. Around 610,000 mine workers struck that year, including the 155,000 anthracite and 155,000 bituminous miners.