Lobegott Friedrich Constantin (von) Tischendorf was a German biblical scholar. In 1844, he discovered the world's oldest and most complete Bible dated to around the mid-4th century and called Codex Sinaiticus after Saint Catherine's Monastery at Mount Sinai.

The Codex Sinaiticus, designated by siglum א [Aleph] or 01, δ 2, also called Sinai Bible, is a fourth-century Christian manuscript of a Greek Bible, containing the majority of the Greek Old Testament, including the deuterocanonical books, and the Greek New Testament, with both the Epistle of Barnabas and the Shepherd of Hermas included. It is written in uncial letters on parchment. It is one of the four great uncial codices. Along with Codex Alexandrinus and Codex Vaticanus, it is one of the earliest and most complete manuscripts of the Bible, and contains the oldest complete copy of the New Testament. It is a historical treasure, and using the study of comparative writing styles (palaeography), it has been dated to the mid-fourth century.

The Codex Vaticanus, designated by siglum B or 03, δ 1, is a Christian manuscript of a Greek Bible, containing the majority of the Greek Old Testament and the majority of the Greek New Testament. It is one of the four great uncial codices. Along with Codex Alexandrinus and Codex Sinaiticus, it is one of the earliest and most complete manuscripts of the Bible. Using the study of comparative writing styles (palaeography), it has been dated to the 4th century.

Mark 16 is the final chapter of the Gospel of Mark in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. Christopher Tuckett refers to it as a "sequel to the story of Jesus' death and burial". The chapter begins after the sabbath has ended, with Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome purchasing spices to bring to the tomb next morning to anoint Jesus' body. There they encounter the stone rolled away, the tomb open, and a young man dressed in white who announces the resurrection of Jesus. The two oldest manuscripts of Mark 16 conclude with verse 8, which ends with the women fleeing from the empty tomb, and saying "nothing to anyone, because they were too frightened".

The Codex Alexandrinus, designated by the siglum A or 02, δ 4, is a manuscript of the Greek Bible, written on parchment. Using the study of comparative writing styles (palaeography), it has been dated to the fifth century. It contains the majority of the Greek Old Testament and the Greek New Testament. It is one of the four Great uncial codices. Along with Codex Sinaiticus and Vaticanus, it is one of the earliest and most complete manuscripts of the Bible.

Eusebian canons, Eusebian sections or Eusebian apparatus, also known as Ammonian sections, are the system of dividing the four Gospels used between late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. The divisions into chapters and verses used in modern texts date only from the 13th and 16th centuries, respectively. The sections are indicated in the margin of nearly all Greek and Latin manuscripts of the Bible, but can be also found in periphical Bible transmissions as Syriac and Christian Palestinian Aramaic 5th to 8th century, and in Ethiopian manuscripts until the 14th and 15th centuries, with a few produced as late as the 17th century. These are usually summarized in canon tables at the start of the Gospels. There are about 1165 sections: 355 for Matthew, 235 for Mark, 343 for Luke, and 232 for John; the numbers, however, vary slightly in different manuscripts.

A biblical manuscript is any handwritten copy of a portion of the text of the Bible. Biblical manuscripts vary in size from tiny scrolls containing individual verses of the Jewish scriptures to huge polyglot codices containing both the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) and the New Testament, as well as extracanonical works.

Codex Vaticanus, designated by S or 028, ε 1027, formerly called Codex Guelpherbytanus, is a Greek manuscript of the four Gospels which can be dated to a specific year instead of an estimated range. The colophon of the codex lists the date as 949. This manuscript is one of the four oldest New Testament manuscripts dated in this manner, and the only dated uncial.

Uncial 030, designated by siglum U or 030, ε 90, is a Greek uncial manuscript of the New Testament on parchment, dated palaeographically to the 9th century. The manuscript has complex contents, with full marginalia.

Codex Coislinianus designated by Hp or 015, α 1022 (Soden), was named also as Codex Euthalianus. It is a Greek uncial manuscript of the Pauline epistles, dated palaeographically to the 6th century. The text is written stichometrically. It has marginalia. The codex is known for its subscription at the end of the Epistle to Titus.

Codex Nitriensis, designated by R or 027, ε 22, is a 6th-century Greek New Testament codex containing the Gospel of Luke, in a fragmentary condition. It is a two column manuscript in majuscules, measuring 29.5 cm by 23.5 cm.

Codex Basilensis A. N. IV. 2 is a Greek minuscule manuscript of the entire New Testament, apart from the Book of Revelation. Using the study of comparative writings styles (palaeography), it is usually dated to the 12th century CE. It is known as Minuscule 1, δ 254, and formerly designated by 1eap to distinguish it from minuscule 1rK.

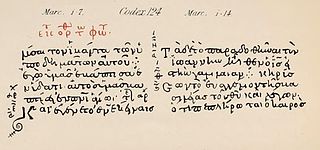

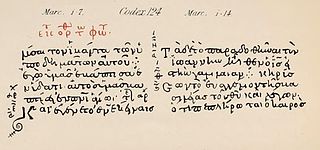

Minuscule 124, ε 1211, is a Greek minuscule manuscript of the New Testament, written on parchment. Using the study of comparative writings styles (palaeography), it has been assigned to the 11th century. It has marginalia and liturgical matter.

Minuscule 157 is a Greek minuscule manuscript of the New Testament Gospels, written on parchment. It is designated as 157 in the Gregory-Aland numbering of New Testament manuscripts, and ε207 in the von Soden numbering of New Testament manuscripts. According to the colophon it is dated to the year 1122. The date had been wrongly deciphered formally as 1128. It has complex contents and full marginal notations.

Minuscule 365, δ 367 (Soden), is a Greek minuscule manuscript of the New Testament with some parts of the Old Testament, on parchment. Paleographically it has been assigned to the 12th century. It has marginalia.

Minuscule 480, δ 462, is a Greek minuscule manuscript of the New Testament, on parchment. It is dated by a colophon to the year 1366. The manuscript is lacunose. The manuscript was adapted for liturgical use. It has marginalia. It contains liturgical books with hagiographies: Synaxarion and Menologion.

Minuscule 482, ε 1017, is a Greek minuscule manuscript of the New Testament, on parchment. It is dated by a colophon to the year 1285 . Scrivener labelled it by number 570. The manuscript has complex context, but faded in parts. The text exhibits more numerous and bolder textual variants than usual manuscripts of the four Gospels. Marginal apparatus is given fully.

Minuscule 496, δ 360, is a Greek minuscule manuscript of the New Testament, on parchment. Palaeographically it has been assigned to the 13th-century. Scrivener labelled it by number 582. The manuscript has complex contents with full marginalia and liturgical books.

Lectionary 300, designated by siglum ℓ300 is a Greek manuscript of the New Testament, written on parchment. It has been palaeographically assigned to the 11th century. The manuscript is written in gold ink and contains Gospel lessons for selected days. It was named as "Gospel of Theodosius".

The great uncial codices or four great uncials are the only remaining uncial codices that contain the entire text of the Bible in Greek. They are the Codex Vaticanus in the Vatican Library, the Codex Sinaiticus and the Codex Alexandrinus in the British Library, and the Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris.