Seventeen days after the German invasion of Poland in 1939, which marked the beginning of the Second World War, the Soviet Union entered the eastern regions of Poland and annexed territories totalling 201,015 square kilometres (77,612 sq mi) with a population of 13,299,000. Inhabitants besides ethnic Poles included Belarusian and Ukrainian major population groups, and also Czechs, Lithuanians, Jews, and other minority groups.

The Polish minority in the Soviet Union are Polish diaspora who used to reside near or within the borders of the Soviet Union before its dissolution. Some of them continued to live in the post-Soviet states, most notably in Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine, the areas historically associated with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, as well as in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan among others.

Around six million Polish citizens are estimated to have perished during World War II. Most were civilians killed by the actions of Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, the Lithuanian Security Police, as well as the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and its offshoots.

From 1930 to 1952, the government of the Soviet Union, on the orders of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and under the direction of the NKVD official Lavrentiy Beria, forcibly transferred populations of various groups. These actions may be classified into the following broad categories: deportations of "anti-Soviet" categories of population, deportations of entire nationalities, labor force transfer, and organized migrations in opposite directions to fill ethnically cleansed territories. Dekulakization marked the first time that an entire class was deported, whereas the deportation of Soviet Koreans in 1937 marked the precedent of a specific ethnic deportation of an entire nationality.

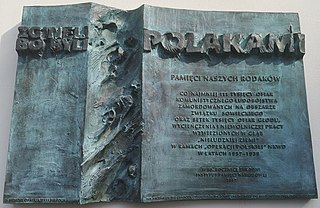

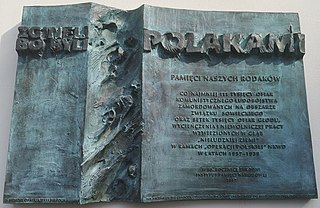

The Polish Operation of the NKVD in 1937–1938 was an anti-Polish mass-ethnic cleansing operation of the NKVD carried out in the Soviet Union against Poles during the period of the Great Purge. It was ordered by the Politburo of the Communist Party against so-called "Polish spies" and customarily interpreted by NKVD officials as relating to 'absolutely all Poles'. It resulted in the sentencing of 139,835 people, and summary executions of 111,091 Poles living in or near the Soviet Union. The operation was implemented according to NKVD Order No. 00485 signed by Nikolai Yezhov.

Operation Vistula was the codename for the 1947 forced resettlement of close to 150,000 Ukrainians from the southeastern provinces of postwar Poland to the Recovered Territories in the west of the country. The action was carried out by the Soviet-installed Polish communist authorities to remove material support to the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. The Ukrainian Insurgent Army continued its guerrilla activities until 1947 in Subcarpathian and Lublin Voivodeships with no hope for any peaceful resolution; Operation Vistula brought an end to the hostilities.

Western Belorussia or Western Belarus is a historical region of modern-day Belarus which belonged to the Second Polish Republic during the interwar period. For twenty years before the 1939 invasion of Poland, it was the northern part of the Polish Kresy macroregion. Following the end of World War II in Europe, most of Western Belorussia was ceded to the Soviet Union by the Allies, while some of it, including Białystok, was given to the Polish People's Republic. Until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Western Belorussia formed the western part of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR). Today, it constitutes the west of modern Belarus.

A sybirak is a person resettled to Siberia. Like its Russian counterpart sibiryák, the word can refer to any dweller of Siberia, but it more specifically refers to Poles imprisoned or exiled to Siberia or even to those sent to the Russian Arctic or to Kazakhstan in the 1940s.

The June deportation of 1941 was a mass deportation of tens of thousands of people during World War II from Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, present-day western Belarus and western Ukraine, and present-day Moldova – territories which had been occupied by the Soviet Union in 1939–1940 – into the interior of the Soviet Union.

The Polish minority in Belarus numbers officially 288,000 according to 2019 census. However, according to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Poland the number is as high as 1,100,000. It forms the second largest ethnic minority in the country after the Russians, at around 3.1% of the total population according to the official census. According to the official census, an estimated 205,200 Belarusian Poles live in large agglomerations and 82,493 in smaller settlements, with the number of women exceeding the number of men by 33,905. Some estimates by Polish non-governmental sources in the U.S. are higher, citing the previous poll held in 1989 under the Soviet authorities with 413,000 Poles recorded and the census of 1959 with 538,881 Poles recorded in Belarus.

Pavlivka is a town now located in northwestern Ukraine, in Volodymyr Raion of Volyn Oblast, near Volodymyr, on the Luha river. For centuries, Poryck was property of several noble Polish families. The town is the birthplace of a Polish statesman Tadeusz Czacki. On 11 July 1943, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, supported by local nationalists murdered here more than 300 Polish civilians, who had gathered in a local Roman Catholic church for a Sunday ceremony.

The Polish population transfers in 1944–1946 from the eastern half of prewar Poland, were the forced migrations of Poles toward the end and in the aftermath of World War II. These were the result of a Soviet Union policy that had been ratified by the main Allies of World War II. Similarly, the Soviet Union had enforced policies between 1939 and 1941 which targeted and expelled ethnic Poles residing in the Soviet zone of occupation following the Nazi-Soviet invasion of Poland. The second wave of expulsions resulted from the retaking of Poland from the Wehrmacht by the Red Army. The USSR took over territory for its western republics.

Amnesty for Polish citizens in USSR was the one-time amnesty in the USSR for those deprived of their freedom following the Soviet invasion of Poland in World War II. The signing of amnesty by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet on 12 August 1941, resulted in temporary stop of persecutions of Polish citizens under the Soviet occupation. Their mass persecution accompanied the 1939 annexation of the entire eastern half of the Second Polish Republic in accordance with the Nazi-Soviet Pact against Poland. In order to de-Polonize all newly acquired territories, the Soviet NKVD rounded up and deported between 320,000 and 1 million Polish nationals to the eastern parts of the USSR, the Urals, and Siberia in the atmosphere of terror. There were four waves of deportations of entire families with children, women and elderly aboard freight trains from 1940 until 1941. The second wave of deportations by the Soviet occupational forces across Kresy, affected 300,000 to 330,000 Poles, sent primarily to Kazakh SSR. The amnesty of 1941 was directed specifically at Polish victims of those deportations.

In the aftermath of the German and Soviet invasion of Poland, which took place in September 1939, the territory of Poland was divided between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. The Soviets had ceased to recognise the Polish state at the start of the invasion. Since 1939 German and Soviet officials coordinated their Poland-related policies and repressive actions. For nearly two years following the invasion, the two occupiers continued to discuss bilateral plans for dealing with the Polish resistance during Gestapo-NKVD Conferences until Germany's Operation Barbarossa against the Soviet Union, in June 1941.

On the basis of a secret clause of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, the Soviet Union invaded Poland on September 17, 1939, capturing the eastern provinces of the Second Polish Republic. Lwów, the capital of the Lwów Voivodeship and the principal city and cultural center of the region of Galicia, was captured and occupied by September 22, 1939 along with other provincial capitals including Tarnopol, Brześć, Stanisławów, Łuck, and Wilno to the north. The eastern provinces of interwar Poland were inhabited by an ethnically mixed population, with ethnic Poles as well as Polish Jews dominant in the cities, and ethnic Ukrainians dominating the countryside and overall. These lands now form the backbone of modern Western Ukraine and West Belarus.

Following the Soviet invasion of Poland at the onset of World War II, in accordance with the Nazi–Soviet Pact against Poland, the Soviet Union acquired more than half of the territory of the Second Polish Republic or about 201,000 square kilometres (78,000 sq mi) inhabited by more than 13,200,000 people. Within months, in order to de-Polonize annexed lands, the Soviet NKVD rounded up and deported between 320,000 and 1 million Polish nationals to the eastern parts of the USSR, the Urals, and Siberia. There were four waves of deportations of entire families with children, women, and elderly people aboard freight trains from 1940 until 1941. The second wave of deportations by the Soviet occupational forces across the Kresy macroregion, affected 300,000 to 330,000 Poles, sent primarily to Kazakhstan.

Around 6 million Polish citizens perished during World War II: about one fifth of the entire pre-war population of Poland. Most of them were civilian victims of the war crimes and the crimes against humanity which Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union committed during their occupation of Poland. Approximately half of them were Polish Jews who were killed in The Holocaust. Statistics for Polish casualties during World War II are divergent and contradictory. This article provides a summary of the estimates of Poland's human losses in the war as well as a summary of the causes of them.

The Monument to the Fallen and Murdered in the East is a monument in Warsaw, Poland which commemorates the victims of the Soviet invasion of Poland during World War II and subsequent repressions. It was unveiled on 17 September 1995, on the 56th anniversary of the Soviet invasion of 1939.

The occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union during World War II (1939–1945) began with the Invasion of Poland in September 1939, and it was formally concluded with the defeat of Germany by the Allies in May 1945. Throughout the entire course of the occupation, the territory of Poland was divided between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union (USSR), both of which intended to eradicate Poland's culture and subjugate its people. In the summer-autumn of 1941, the lands which were annexed by the Soviets were overrun by Germany in the course of the initially successful German attack on the USSR. After a few years of fighting, the Red Army drove the German forces out of the USSR and crossed into Poland from the rest of Central and Eastern Europe.

Soviet leaders and authorities officially condemned nationalism and proclaimed internationalism, including the right of nations and peoples to self-determination. Soviet internationalism during the era of the USSR and within its borders meant diversity or multiculturalism. This is because the USSR used the term "nation" to refer to ethnic or national communities and or ethnic groups. The Soviet Union claimed to be supportive of self-determination and rights of many minorities and colonized peoples. However, it significantly marginalized people of certain ethnic groups designated as "enemies of the people", pushed their assimilation, and promoted chauvinistic Russian nationalistic and settler-colonialist activities in their lands. Whereas Vladimir Lenin had supported and implemented policies of korenizatsiia, Joseph Stalin reversed much of the previous policies, signing off on orders to deport and exile multiple ethnic-linguistic groups brandished as "traitors to the Fatherland", including the Balkars, Crimean Tatars, Chechens, Ingush, Karachays, Kalmyks, Koreans and Meskhetian Turks, with those, who survived the collective deportation to Siberia or Central Asia, were legally designated "special settlers", meaning that they were officially second-class citizens with few rights and were confined within small perimeters.