Article

The failure of the Aerodrome resulted in public ridicule of Langley. Two days after the failed experiment, the editorial "Flying Machines Which Do Not Fly" was published in the New York Times. It opined: [5] [6]

[It] might be assumed that the flying machine which will really fly might be evolved by the combined and continuous efforts of mathematicians and mechanicians in from one million to ten million years... No doubt the problem has attractions for those it interests, but to the ordinary man it would seem as if effort might be employed more profitably.

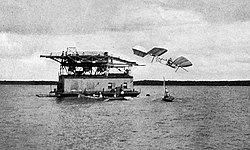

On the same day as the published article, Orville Wright wrote in his diary, "We started assembly today", in reference to the first airplane that he and his brother, Wilbur, would fly shortly thereafter. [7] On December 8, 1903 Langley made a final attempt to fly his Aerodrome. Once again, the experiment failed and official support for Langley's project was withdrawn. Another New York Times editorial commented: [8]

We hope that Professor Langley will not put his substantial greatness as a scientist in further peril by continuing to waste his time and money for further airship experiments. Life is short, and he is capable of services to humanity incomparably greater than can expected to result from trying to fly ...

On December 17, 1903, the Wright brothers disproved the New York Times—and many other doubters—with the successful flight of their airplane. [5]