The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy, are a group of related Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands in the United States of America. Their historical homelands are in what now comprises southern Tennessee, much of Alabama, western Georgia and parts of northern Florida.

Lauderdale County is a county located in the northwestern corner of the U.S. state of Alabama. At the 2020 census the population was 93,564. Its county seat is Florence. Its name is in honor of Colonel James Lauderdale, of Tennessee. Lauderdale is part of the Florence-Muscle Shoals, AL Metropolitan Statistical Area, also known as "The Shoals".

The Chickasaw are an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, United States. Their traditional territory was in northern Mississippi, northwestern and northern Alabama, western Tennessee and southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classified as a member of the Muskogean language family. In the present day, they are organized as the federally recognized Chickasaw Nation.

Elkmont is a town in Limestone County, Alabama, United States, and is included in the Huntsville-Decatur Combined Statistical Area. As of the 2010 census, the population of the town was 434, down from its record high of 470 in 2000.

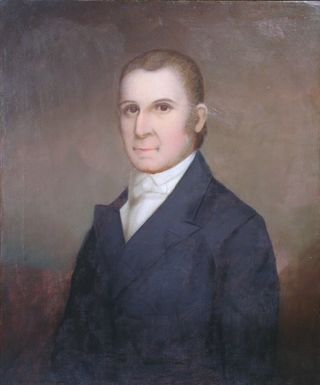

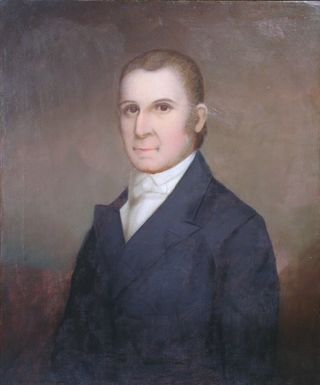

Willie Blount was an American politician who served as the third Governor of Tennessee from 1809 to 1815. Blount's efforts to raise funds and soldiers during the War of 1812 earned Tennessee the nickname, "Volunteer State." He was the younger half-brother of Southwest Territory governor, William Blount. He was a member of the Democratic-Republican Party.

The Creek War, was a regional conflict between opposing Native American factions, European powers, and the United States during the early 19th century. The Creek War began as a conflict within the tribes of the Muscogee, but the United States quickly became involved. British traders and Spanish colonial officials in Florida supplied the Red Sticks with weapons and equipment due to their shared interest in preventing the expansion of the United States into regions under their control.

Red Sticks —the name deriving from the red-painted war clubs of some Native American Creek—refers to an early 19th century traditionalist faction of Muscogee Creek people in the Southeastern United States. Made up mostly of Creek of the Upper Towns that supported traditional leadership and culture, as well as the preservation of communal land for cultivation and hunting, the Red Sticks arose at a time of increasing pressure on Creek territory by European American settlers. Creek of the Lower Towns were closer to the settlers, had more mixed-race families, and had already been forced to make land cessions to the Americans. In this context, the Red Sticks led a resistance movement against European American encroachment and assimilation, tensions that culminated in the outbreak of the Creek War in 1813. Initially a civil war among the Creek, the conflict drew in United States state forces while the nation was already engaged in the War of 1812 against the British.

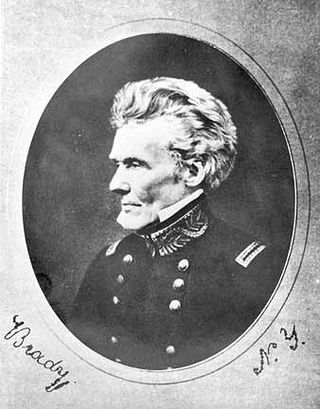

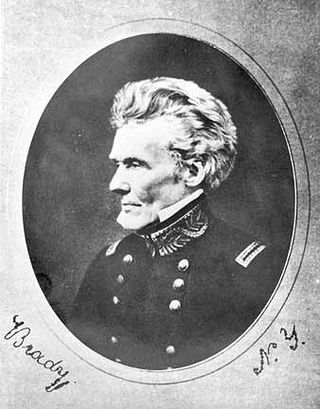

Edmund Pendleton Gaines was a career United States Army officer who served for nearly fifty years, and attained the rank of major general by brevet. He was one of the Army's senior commanders during its formative years in the early to mid-1800s, and was a veteran of the War of 1812, Seminole Wars, Black Hawk War, and Mexican–American War.

John R. Coffee was an American planter of Irish descent, and a state militia brigadier general in Tennessee. He commanded troops under General Andrew Jackson during the Creek Wars (1813–14) and during the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812.

The Fort Mims massacre took place on August 30, 1813, during the Creek War, when a force of Creek Indians belonging to the Red Sticks faction, under the command of head warriors Peter McQueen and William Weatherford, stormed the fort and defeated the militia garrison. Afterward, a massacre ensued and almost all of the remaining mixed Creek, white settlers, and militia at Fort Mims were killed. The fort was a stockade with a blockhouse surrounding the house and outbuildings of the settler Samuel Mims, located about 35 miles directly north of present-day Mobile, Alabama.

Chief George Colbert, also known as Tootemastubbe in Chickasaw, was a leader and war chief of the Chickasaw people in the early 19th century, then occupying territory in what are now the jurisdictions of Alabama and Mississippi. During the Creek War of 1813–1814, he commanded 350 Chickasaw auxiliary troops, whom he had recruited, as a militia captain under Andrew Jackson. Later he joined the US Army under Jackson for the remainder of the War of 1812.

Fort Strother was a stockade fort at Ten Islands in the Mississippi Territory, in what is today St. Clair County, Alabama. It was located on a bluff of the Coosa River, near the modern Neely Henry Dam in Ragland, Alabama. The fort was built by General Andrew Jackson and several thousand militiamen in November 1813, during the Creek War and was named for Captain John Strother, Jackson's chief cartographer.

Fort Claiborne was a stockade fort built in 1813 in present-day Monroe County, Alabama during the Creek War.

The Regiment of Riflemen was a unit of the U.S. Army in the early nineteenth century. Unlike the regular US line infantry units with muskets and bright blue and white uniforms, this regiment was focused on specialist light infantry tactics, and were accordingly issued rifles and dark green and black uniforms to take better advantage of cover. This was the first U.S. rifleman formation since the end of the American Revolutionary War 25 years earlier.

Where can you find troops more efficient than Morgan's riflemen of the Revolution or Forsyth's riflemen of the last war with Great Britain?

John Gordon, was an American pioneer, Indian trader, planter, and militia captain in several Indian wars. Part of the post-Revolutionary War settlement of the trans-Appalachian frontier, Gordon was an early settler in the Nashville, Tennessee area. He gained notability and rank in the Tennessee Militia, fighting against the Creeks and Seminoles for Andrew Jackson, during the War of 1812. Jackson referred to him as his "Captain of the Spies."

Fort Decatur was an earthen fort established in March 1814 on the banks of the Tallapoosa River as part of the Creek War and the larger War of 1812. The fort was located on the east bank of the Tallapoosa River, near the modern community of Milstead. Fort Decatur was also located near the Creek town of Tukabatchee. It was most likely named for Stephen Decatur.

Fort Armstrong was a stockade fort built in present-day Cherokee County, Alabama during the Creek War. The fort was built to protect the surrounding area from attacks by Red Stick warriors but was also used as a staging area and supply depot in preparation for further military action against the Red Sticks.

Fort Montgomery was a stockade fort built in August 1814 in present-day Baldwin County, Alabama, during the Creek War, which was part of the larger War of 1812. The fort was built by the United States military in response to attacks by Creek warriors on encroaching American settlers and in preparation for further military action in the War of 1812. Fort Montgomery continued to be used for military purposes but in less than a decade was abandoned. Nothing exists at the site today.

Fort Pierce, was two separate stockade forts built in 1813 in present-day Baldwin County, Alabama, during the Creek War, which was part of the larger War of 1812. The fort was originally built by settlers in the Mississippi Territory to protect themselves from attacks by Creek warriors. A new fort of the same name was then built by the United States military in preparation for further action in the War of 1812, but the fort was essentially abandoned within a few years. Nothing exists at the site today.